|

|

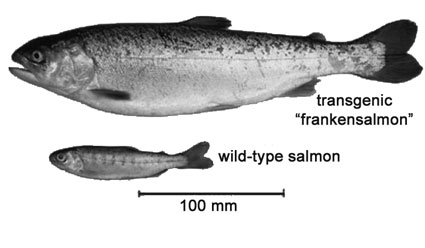

Frankensalmon analysis smells fishyby Ari LeVaux If you want to bury an unsavory news story, the afternoon before Christmas vacation is a good time to break it. The FDA chose Dec. 21 to release its long-awaited Environmental Assessment (EA) of the genetically modified “AquAdvantage” salmon. This move quietly slid the fish closer to making history as the first GM animal approved for human consumption. The public was given 60 days to comment, beginning on the winter solstice, 2012, on a farmed salmon that salmon farmers won’t be allowed to raise in the U.S., but Americans would nonetheless be allowed to eat. If the announcement’s timing suggests FDA wants the application to flow smoothly, also consider that it has been 17 years since AquaBounty first applied for permission to sell its recombinant Atlantic salmon in the U.S. The company has paid a heavy regulatory price for trying to be first. During Bush II, FDA announced it would regulate AquAdvantage salmon as an animal drug rather than food, perhaps in hopes of expediting the process. More recently, according to a hypothesis espoused by Jon Entine in Slate, officials in President Obama’s inner circle conspired to delay the salmon’s approval for political gain. Its application in bureaucratic purgatory for decades, AquaBounty leaked money, sold assets, was often without a clear idea of where the process was going, and flirted with bankruptcy. The tide began turning in November 2012, when biotech giant Intrexon began acquiring AquaBounty shares (ABTX), triggering what has become a 400 percent run-up of the stock – most of the gain since the FDA’s solstice announcement. Meanwhile, many are still wondering how a salmon steak could be considered a drug. According to FDA logic, the drug per se is AquaBounty’s patented genetic construct, made of genes from two other fish inserted into Atlantic salmon DNA. Inserted at the animal’s one-cell stage, the gene sequence exists in every cell of the adult fish’s body. The company claims this cluster of genes, aka the drug, makes AquAdvantage salmon grow faster than its non-GM, farm-raised counterparts, and it hopes to sell that claim, and lots of AquAdvantage salmon eggs, to fish farmers around the world. But unlike most other so-called animal drugs, this one inhabits an animal that can do very well for itself in the wild. It can swim across oceans, up rivers, mate with wild fish, and pass along its drugs to the next generation. Given precedent that will be set in approving the first GM animal for human consumption, it’s understandable that the review process might take some time. Unfortunately, the FDA has spent most of its time figuring out how to avoid asking some tough but very important questions. AquAdvantage eggs are to be produced in a facility on Prince Edward Island, Canada, and shipped to a facility in Panama to be raised in tanks to marketable size. In the future, AquaBounty hopes to ship eggs worldwide from Prince Edward Island – but not to the United States, or any other country, apparently, with sturdy environmental laws. A key step in the AquAdvantage approval process came in September 2010, when FDA held a public meeting of its Veterinary Medicine Advisory Committee (VMAC) to review what was then the draft EA. Jon Entine, of the Team Obama interference hypothesis, assumes the VMAC committee “unanimously endorsed the FDA’s findings that the salmon was safe.” But the meeting transcript paints a more nuanced picture. VMAC member Dr. James McKean noted, in his final remarks, of AquAdvantage salmon, “It appears to be safe, but that loop has not, in my mind, been closed.” Purdue biologist Bill Muir commented at the VMAC, has looked extensively at risk associated with GM fish, and believes AquAdvantage salmon don’t pose much of an ecological threat. Nonetheless, as he explained to the New York Times, “Shit always happens. If shit happens and they end up somehow in the ocean ... maybe it’s hypothetical to the FDA, but people would like to know what happens.” In fact, shit did happen at AquaBounty’s Panama location in 2008, when a storm swamped the facility. As AquaBounty reported to investors, the largest batch of salmon in company history was lost. According to the Christmas EA, meanwhile, “no serious damage was incurred by this event, and no problems of significance to aquaculture operations occurred.” Dartmouth sustainability science professor Anne Kapuscinski addressed the committee as well. Like the rest of the public, Kapuscinski had barely two weeks to review the hundreds of pages of documents released the Friday before Labor Day. Dr. Kapuscinski recently led a team of 53 scientists in writing a book about how to conduct scientifically credible risk assessment of genetically modified fish, and her lab has done ecological-risk research with GM fish. Kapuscinski was one of the most qualified people in the room, VMAC members included, to comment on the ecological risks posed by AquAdvantage salmon. Her oral comments were cut short due to time; she submitted a written transcript of those comments, but I was not able to find it in the FDA website. A copy of her oral comments that Kapuscinski forwarded to me stated: “The Environmental Assessment does not adequately consider the growing body of research on genetic and ecological risks of transgenic fish.” The EA, she wrote, lacked the basic quantitative information necessary to verify its conclusions. The statistical methods were outdated, and sample sizes too small or not reported. Kapuscinski called for “a transparent Environmental Impact Statement that completes genetic and ecological risk assessment.” In person, according to the VMAC transcript, Kapuscinski advised the committee, “FDA should require a quantitative failure mode analysis for all the confinement methods. Failure mode analysis is standard practice for technology assessment.” The Christmas EA, in explaining its decision to not follow Kapuscinski’s guidelines, cited her work 14 times. An EIS would be a sensible if, less convenient, alternative to approving an EA that depends on exporting fish farming to other people’s back yards, and sending U.S. agents to the ends of the earth to inspect the facilities of fish farms that want to raise AquAdvantage salmon and sell it to the U.S. To claim that AquAdvantage salmon is safe to produce, while at the same time circumventing the process of regulating its production at home, sends a mixed message to consumers, environmentalists and industry. It also reeks of colonialism, and serves as a reminder of why “animal drug” might not be the most productive way to describe this fish. n |

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel