|

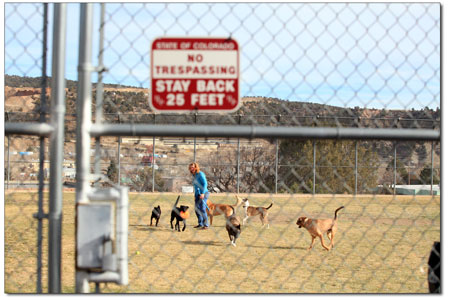

| Volunteer dog trainer Barb West mingles with a pack of shelter dogs at the DeNier Center in December. A unique program between DeNier and the Humane Society pairs shelter dogs with juveniles, who train the dogs to make them more adoptable./Photo by Steve Eginoire |

Dog days at DeNier

Dog training program prepares youth, dogs for outside world

by Jen Reeder

Crisp air blows a teen-age girl’s hair as she kneels to hug a pound puppy named Lucky. The 6-month-old miniature Rottweiler wound up at the La Plata County Humane Society Animal Shelter after being rescued from a yard where she was chained so tightly that she couldn’t stand upright. A wagging tail shows she’s much happier in the arms of her new friend.

Crisp air blows a teen-age girl’s hair as she kneels to hug a pound puppy named Lucky. The 6-month-old miniature Rottweiler wound up at the La Plata County Humane Society Animal Shelter after being rescued from a yard where she was chained so tightly that she couldn’t stand upright. A wagging tail shows she’s much happier in the arms of her new friend.

“She’s so cute!” the teen says.

The idyllic scene takes place in an unusual setting: the exercise yard at Robert E. DeNier Youth Services Center, Durango’s juvenile detention center. Three Wednesdays a month, volunteers from the Animal Shelter teach a few select students to train dogs in obedience skills that will help the animals’ chances for adoption.

“I’ve wanted to do this forever,” says Barb West, the volunteer dog trainer.

How long has she been taking dogs to DeNier?

“Oh, I’ve had too many strokes to remember,” she says. “If I forget a word, please give it to me.”

Strokes and heart issues may have wreaked havoc on West’s body and sometimes her memory, but her experience as a professional dog trainer is so ingrained that teaching the kids how to handle the dogs is second nature to her, as is her passion for the program. When Lucky bites at her leash instead of sitting still, West doesn’t hesitate to offer a solution to her new handler.

“Pull the leash straight up,” West says.

Ken Hibbard, education and outreach coordinator at the La Plata County Humane Society, who started the program in February 2011, leans in and whispers to the girl, “That’s why we brought her here – so you can help her.”

Hibbard greets the four students whose exemplary behavior earned them the chance to train dogs this week. They wear matching grey sweatshirts, black or maroon sweatpants, and smiles as they learn each dog’s story. Hibbard gestures to a barking pit bull.

“Pocket is real sweet, but his owner was a college kid who left him alone a lot, so he started tearing up the furniture,” he says.

“If he’s barking, don’t reward him by petting him,” West adds, nodding to his handler, who stops.

A few of the students have trained dogs with West and Hibbard before and ask how dogs they know are doing.

“Diesel got adopted, and Elvis found a home, too,” Hibbard says, garnering cheers.

West teaches the group how to get the dogs to walk on leash and prevent pulling. If anyone bends a rule, it’s to sneak a treat to a dog, or pause to see if they know how to “shake.” One male student takes a break and sits down; his blond German shepherd, Cassie, immediately sits on his lap, looking like a protective guardian. The boy’s arms wrap around the dog, and the two hold the pose for several minutes. Hibbard points and says, “That’s it – right there.”

But there are no cameras to capture the moment, since photography is not allowed inside the locked, fenced area.

“Now let’s switch to teaching them to sit,” West says. “Who knows how to teach a dog to sit?”

Someone mentions choke collars, but West suggests a different technique.

“Hold a treat in a fist above their heads. Keep moving it back until they have to sit down to keep their noses near it. When they sit, reward them with the treat quickly,” she says before walking to each student to offer personal assistance. Soon several dogs are off-leash, obediently taking two steps forward before sitting for a treat – even Pocket, the formerly neglected pit bull.

“He wasn’t great on the leash, but I got him to sit when I use a clicker, so at least he learned one thing today,” says his teen-aged handler.

As Hibbard points out, behavioral skills like “sit” can make the difference between a dog being adopted or passed over at the shelter. And while the students are helping the dogs, they’re also helping themselves.

“It definitely helps them with patience, because they learn what it’s like not to be able to control something,” says Taber Powers, program director at Robert E. DeNier Youth Services Center. “They really enjoy being able to help someone else. They apply a lot of the stuff they’re learning in their own program to how they’re responding with the dogs.”

A typical day for a student at DeNier involves academic classes, physical fitness workouts and treatment groups for issues like anger management, drugs and alcohol, victim empathy, and cognitive/behavioral therapy. Time is also allotted for sports and vocational interests, such as dog training. The limited space on the recreation field, which is about 50 yards long, means not everyone can participate in the dog training each week; there are up to 28 students a day at DeNier. So they earn the privilege by working on their treatment programs.

“Once a kid goes out there once, they want to keep going there so they can work with their dog over and over again,” Powers says. “It’s a good incentive.”

Powers recalls a “notable therapeutic experience” for a student who was attacked by a dog at a young age and traumatized by it. Then the student participated in the dog training program – and ended up with “zero fear of dogs.”

Bonds also form between students and the volunteers from the Humane Society. When a DeNier staff member announces to the yard that it’s “time to line up,” the students shake hands with the shelter volunteers and say things like “Thank you” and “I had fun.” Lucky’s handler even casts a wistful backward glance and says a three-syllable “Aww” with separation anxiety.

Hibbard just grins and gestures to the dogs.

“If these guys get out for a few hours, and the kids get to do something different, helping them learn, then I’ve had a pretty good day,” he says.

And one by one, Pocket, Cassie, Indiana, Brodie, Millie and Lucky had very good days, when each dog was adopted – just in time for Christmas.

The La Plata County Humane Society is located at 1111 South Camino del Rio. To make a donation, call 970-259-2847, or visit www.lpchumanesociety.org/donateonline.html

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel