|

|

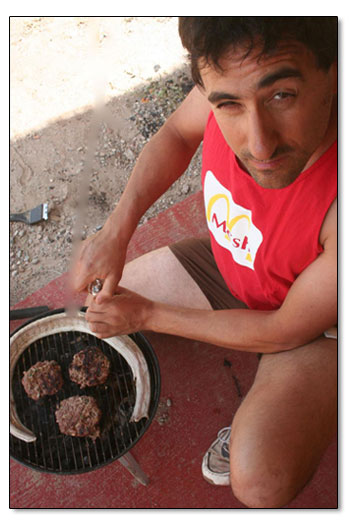

How to cook a rattlesnakeby Ari Levaux A neighbor in New Mexico once told me that it’s bad luck, not to mention bad form, to kill a rattlesnake. Unfortunately, he told me this after I’d already killed one. My neighbor had lived on that mountain most of his life, and he was at peace, if not in love, with its snakes, including rattlers. Although he’s never been bitten, he has lost dogs. The snakes were here first, he told me, and they’re better for the landscape than we are. If you kill one, he said, you will be the last thing it sees, and your image will remain in its eyes. If another snake looks at those dead eyes, it will know who killed it. The rattlesnake I had killed was sleeping in the garden, beneath a tomato plant, when my wife noticed it. There’s something about a snake in the garden, even to a Hebrew-school dropout like myself, that’s creepier than a snake anywhere else. It didn’t help that wifey was barefoot and pregnant. The snake wasn’t bothering her, she said, so she continued picking tomatoes peacefully, with frequent glances toward the slumbering serpent. Although she was pretty chill about the whole thing, when she told me my lizard brain took over. A better man would have captured the snake and moved it to safer turf, but I felt nothing but fear, and I didn’t know how to catch one. I grabbed a square-edged shovel and used the flat blade to pin the snake behind its head. I finished it with a machete, and threw the head into an arroyo behind the house. I tossed the body into the chicken yard, next to a boulder where I keep the water dish. I had thought the hens might peck at the dead snake, as they often do with meat scraps, but they wanted nothing to do with it. For about 10 minutes the headless body continued to writhe slowly in the dust, which did not entice the chickens any closer. As the days went by, the girls continued to avoid the snake, which sank into the dirt in front of the rock. I had to move the water dish so they would drink, but I figured it would start to rot soon enough, and the smell and insects would draw the chickens in for a snack. As the snake faded from view, I let it disappear from my list of things to do. When my neighbor told me not to kill rattlesnakes, I felt bad about it, and promised myself I’d never do it again. And I hoped no other rattler would find the severed head in the arroyo and see my reflection in its eyes. A few weeks later, arriving home from a night out, I went into the chicken yard to lock the coop. The car’s headlights were on so I could see. As I passed where the dead snake was, I narrowly missed stepping on another one. A live one. It hissed violently, its mouth open wide, and rattled furiously. The rattle was surprisingly high-pitched. So was the screech I let out as I jumped onto a nearby boulder. I didn’t know if the snake had come for me, the chickens or the eggs they were incubating. But the coop is much closer to the house than the garden is, my wife was even more pregnant than she’d been, and I was pissing in my pants. I never, for a second, considered not killing it. When I moved in with the shovel, the snake struck it like a bolt of lightning. My hands felt the shock and my ears heard the ping of fangs on metal. I backed off, grabbed some baseball-sized rocks, and pelted the snake. After a few hits it was stunned, and I went back in with the shovel. Just like that, I’d done it again. This time I buried the head. I skinned and gutted the body. It was my first time cleaning a snake, but it was hardly different from any other animal. What remained was little more than a hollow tube, defined by a dense shield of delicate, circular ribs covered in a thin layer of flesh. I soaked it in a pot of salt water. After a few hours, I rinsed it, let it air-dry, and put it in the fridge. The next day, I threw the snake on the grill alongside some burgers. It tasted almost like chicken, cliché be damned. But it was a bit tough, and difficult to extract in decent-sized pieces. I had intentionally cooked the snake with no seasoning, wanting to experience its true flavor and because the meal was as much communion as gastronomic adventure. The unflavored snake was just a single note compared to the symphony of a well-constructed burger, but I was just glad I hadn’t puked it up. I put the rest in the fridge and slept on it. The answer arrived on a run the next morning. I simmered the snake in water for about 2 hours, until the flesh was soft. I strained the water and teased the flesh off the bones, ending up with less than a cup of snake meat. I baked the meat at 350 in a cast-iron skillet. Meanwhile, I scraped the prickles off the prickly pears with a butter knife under the faucet. When the fruits were clean I added them to the skillet. After about 25 minutes, they started to collapse, and I added chopped garlic and stirred. When the garlic was cooked, I served the dish. The prickly pear fruits, sweet and fragrant, were the highlight. The garlic cloves too were spectacular. The rattlesnake still tasted like chicken: crispy, dry chicken, though nicely balanced by the cactus fruit. It was the best that snake ever tasted, but that’s only saying so much. I hope it’s the last snake I eat. Luckily, it was the last rattlesnake we ever saw on the property. |

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel