|

|

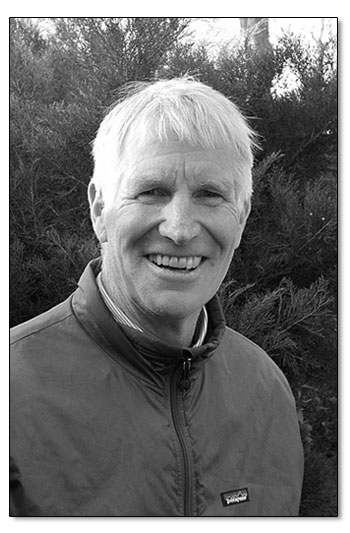

Randy Udall, founder of the Association for Study of Peak Oil-USA

|

Breathing room

Natural gas boom takes heat off, but for how long?

by Allen Best

For several decades, the United States was haunted by what energy analyst Randy Udall calls the “specter of depletion.” Despite robust drilling, domestic supplies of oil and natural gas continued to decline.

For several decades, the United States was haunted by what energy analyst Randy Udall calls the “specter of depletion.” Despite robust drilling, domestic supplies of oil and natural gas continued to decline.

Books such as The End of Oil and High Noon for Natural Gas proclaimed the imminent end of easy access to hydrocarbons that had fueled growth of the U.S. and, really, the world economy.

That narrative has been forced to take a back seat recently. Those books might still be accurate in the long run, but for now, it’s rock ’n’ roll as new technology pries hydrocarbons from tightly congealed formations deep underground. Talk abounds in the United States of “energy independence,” a rhetorical shake of the fist at Venezuela, Saudi Arabia and oil-exporting countries. There’s even talk about exporting natural gas.

Udall, who has both a brother and a cousin in the U.S. Senate, has been studying energy since the 1980s, when he first started worrying about global climate change. Later, he directed efforts to ramp up energy efficiency and renewables in Aspen. About a decade ago, he co-founded a group called Association for the Study of Peak Oil-USA.

Repercussions of this boom are giant. For the average American, this bounty of gas means savings of $300 to $400 a year, said Udall.

U.S. per-capita emissions of greenhouse gasses have stabilized, even dropped, as plants that burn coal are being replaced by plants that burn natural gas, which is cheaper and produces only half the carbon dioxide. Coal has dropped from 52 percent of electrical production eight years ago to just 43 percent now. Some analysts expect a further drop to 35 percent this decade.

What happened? In a recent talk in Golden, Udall pointed to technology, and persistence by drillers. “It’s wizardry. It’s beyond technology what these guys are doing,” he said of efforts to extract natural gas and oil from shale formations.

Hydrofracturing, if much reviled, is one of the key advances. Used since the 1940s, the technique has been improved and is crucial to extracting natural gas that is encased in tightly bound particles of sand. But there are other techniques, too. Udall observed that computers may be employed more extensively in drilling than any other industry.

Panels of speakers at the Vail Global Energy Forum held last month agreed that this bounty of natural gas gives the United States breathing room to figure out more sustainable energy sources that pose less risk of climate change. The flip side is figuring out greater efficiency of existing energy, which also has many challenges.

For now, most of the talk is about whether fracking poses danger to humans and ecosystems. The controversy has mostly surrounded the use of chemicals added to water and sand to expedite flow of gas from tightly spaced rock formations.

Jim Brown, president of Western Hemisphere for Haliburton, said that there has been no confirmed case of fracking solutions entering potable water sources in the United States. Natural gas-bearing formations are deep underground, separated from near-surface water aquifers by layers of dense rock. More than 1 million “fracks” have been done in North America, 400,000 alone since the turn of the century. He said the concern should be focused not on fracking, bur rather on integrity of well-bore casings, the concrete sleeves that prevent fluids and gas from escaping.

Another speaker, Mark Zoback, a professor of geophysics at Stanford University who studies extraction of gas and oil, agreed that concerns about fracking have been misguided. Zoback, however, stressed the need for oversight and healthy skepticism about the integrity of the drilling process. He pointed to BP’s Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico.

Environmental safety, he explained “all comes down to three things: well construction, well construction, well construction.”

“It’s not sexy. It’s very basic,” he said. “When you drill 20,000 wells a year, that’s 20,000 potential problems. We have to be sure we’re doing this right.”

A greater problem yet for natural gas may be fugitive emissions. Methane, the primary constituent, has 20 to 100 times the heat-trapping properties of carbon dioxide. If allowed to escape into the atmosphere, the damage might well negate its value in displacing coal.

For that reason, broad use of natural gas in transportation should be done carefully, said Sally Benson, a professor of energy resources engineering at Stanford and director of the university’s Global Climate and Energy Project.

Furthermore, if people in places like Africa are to achieve greater well-being as enjoyed by people in advanced countries, the world may need six times more energy than it now consumes. That’s a daunting statistic, but Benson also delivered a hopeful thought. Africa leap-frogged conventional phone lines and poles, instead proceeding immediately to cell phones. Might it similarly bypass the dependence on fossil fuels?

Sunshine is the most abundant and promising fuel, and natural gas is a perfect partner for solar and other renewables. “I think we need to deflect the idea they’re in competition,” she said.

But she also emphasized that while the glut of natural gas provides breathing room, it cannot be used as an excuse for becoming less diligent about improving renewables. “That would be a terrible, terrible mistake,” she said.

But for now, we’re in a drilling frenzy. Udall described drilling as the dominant land use in the United States, with one-sixth of the nation now leased for mineral extraction. And while the gas and oil is flowing, he pointed out the enormous effort to get it. It takes 800 wells in the unconventional sands of Texas to produce the same amount of gas that Kuwait can extract using 35 conventional wells. In other words, as we make the shift to natural gas, the supply can only be sustained, at least in the short term, by more frantic drilling.

Allen Best writes about water and energy when he’s not focused on mountain towns. He can be found at http://mountaintownnews.net

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel