A ‘Walden’ for the 21st century

Man Who Quit Money makes Durango appearance

by Shay M. Lopez

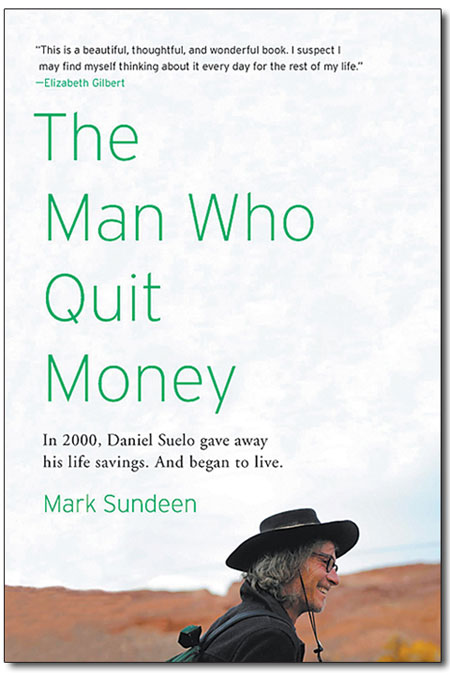

The Man Who Quit Money, by Mark Sundeen, 272 pages, Riverhead Trade publishing.

The Man Who Quit Money, by Mark Sundeen, 272 pages, Riverhead Trade publishing.

I remember sitting down one evening in the summer of 1997 and devouring the story of Christopher McCandless in John Krakauer’s Into the Wild. In my naïve enthusiasm, I lauded McCandless’ panache when he literally ditched his car and money in a desert wash, but I didn’t quite understand his attempt to escape the binds of capitalism by taking a job days later at a Laughlin, Nev., McDonald’s. I could appreciate his devotion to the ideal of living self-sufficiently, although this escapist ideal was one for which McCandless had come less-than-ill-prepared and which ultimately cost him his life. After reading the book, and again after the release of its film counterpart, I heard animated discussions of Into the Wild that see-sawed between “good for him” and “what a dipshit.” I would not be surprised to hear similar reactions to the subject of Mark Sundeen’s new book The Man Who Quit Money.

Sundeen, co-author of the New York Times bestseller North by Northwestern, tells the story of Daniel Suelo, nee Daniel Shellabarger, who, for more than 10 years has not made one monetary transaction. He has not received nor spent a single dollar since the day he put his final 30 bucks in a phone booth and walked away. He realized that the little money he had in his pocket was not the cure of his anxiety but the cause of it.

Suelo now lives in a cave in southern Utah, scavenges food from supermarket and restaurant dumpsters, harvests produce from feral fields. He doesn’t just get by without money, but rather thrives physically, socially and philosophically in a world of his own choosing, outside of money.

Let us try some “free” association. Free: Available without charge, Suelo’s modus operandi. One of the first times Sundeen met Suelo, they feasted on luscious watermelons they’d picked from a field gone fallow. Free: Not subject to engagements or obligations. Suelo recalls, “I watched a daddy longlegs crawl out into the sun from the cave. I must have followed him for four hours.” Free: Not or no longer confined. “I’m employed by the Universe. It doesn’t matter where I am. Wherever I am, I’m at home.” Free: Not observing normal conventions, improvised. Suelo takes what he can get, accepts those things that are freely offered, faithfully allows chance to work in his life.

“Randomness is my guru,” he claims. Free: Generous or lavish. Suelo is not simply a taker, but is free with his few possessions. When Daniel is away from his cave, a note he left reads, “Feel free to camp here. What’s mine is yours. Eat any of my food. Read my books. Take them with you if you’d like.” A good friend of Suelo’s explained how Daniel never comes empty-handed to dinner parties, how his pet watching, house sitting, tree pruning and spiritual counseling are all valuable contributions. Free: Frank or unrestrained. Let’s say “honest.” In one chapter, Sundeen offers a clear and concise history of the credit/debt system that Suelo rightly calls an illusion. “Attachment to illusion makes you illusion, makes you not real. I simply got tired of acknowledging as real this most common worldwide belief called money! I simply got tired of being unreal.” And Daniel Suelo seems, in a word, free.

Where McCandless chose to escape, Suelo has opted to engage, remaining an integral part of the Moab community, a committed friend and an enthusiastic volunteer. And though it would seem that both McCandless and Suelo sought some sort of self-sufficiency, Suelo points out that his experience is just the opposite. “In America we have this idea that everyone should be self-sufficient, pull yourself up by your own bootstraps. A lot of people think that’s why I’m doing this. But really, it’s about acknowledging that there’s not a creature or even a particle in the universe that’s self-sufficient. We’re all dependent on everybody else. I’m dependent on the hard work of other people, just like they’re dependent on mine. But to say we’re all dependent on the money system is a different thing.”

Beyond living outside the system of money, Suelo’s desire to live more authentically on all fronts is at the heart of this story. Sundeen has written a fascinating portrait of the man and how he operates without money, but he has also crafted a very gripping back-story that outlines the religious upbringing, spiritual awakening, sexual discovery and philosophical education of Suelo’s youth, work experiences and travel adventures. We see Suelo in his Canyonlands digs, foraging for wild onions, performing his own Passover ritual with a sacrificial lizard, diving dumpsters for a sack of fried chicken, and, like Chris McCandless, making a few poor decisions on the edibility of wild food. But, as we read of the years and tears leading up to that final $30 being left in a phone booth, we get a sense of Suelo’s intense faith, with nothing of the material world to fall back on.

He quotes Saint Francis, “If we embrace holy poverty very closely, the world will come to us and will feed us abundantly.”

Sundeen’s powerful storytelling reveals the complicated philosophy, the contradictions and shortcomings of someone in the face of grand dreams, and the daily triumphs of someone with the guts to do what many of us wish we could.

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel