|

|

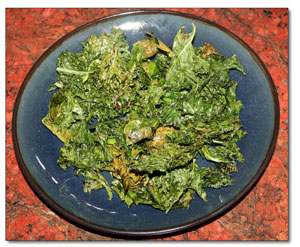

Ninja Chipsby Ari LeVaux It appears that kale is succeeding where spinach and other green things have consistently failed: in the task of getting swallowed by children. The key is to bake the kale into crispy chips. In kale chip taste tests recently conducted in Montana, it was determined that kids will eagerly turn their mouths green with extra helpings. The evidence was convincing enough that the food purchaser for Missoula County Public Schools placed a kale order with a local farm, to be delivered for the fall term. Edward Christensen, assistant supervisor of food and nutrition for Missoula schools, says the taste test was the final and most crucial hurdle, but the fact that kale is so healthful and grows so well in his region makes it especially attractive. “Kale is disease and pest resistant, and cold tolerant. It’s the low-hanging fruit of Montana.” Jason Mandala is the community education director for Garden City Harvest, the nonprofit Missoula farm that got the contract to grow kale for the schools. It was Mandala who sold Christensen on chips as a kid-friendly way to serve a dark-green leafy vegetable in school cafeterias. Though Christensen was impressed, his opinion wasn’t the only one that counted. Only after successful taste tests were conducted at area schools was the deal done. “The kids gobbled them up,” Mandala says. “They taste similar to a potato chip but they’re a lot better for you.” Such repurposing of confiscated marijuana-farming equipment is not as unusual as you might think, says Mary Stein, associate director of the National Farm to School Network. “That’s happening in several places around the country,” she told me. And it’s just one example of how individual farm to school programs can adapt to local opportunities and conditions. “Farm to school programs are as different as the communities they’re part of across the country. In Sitka, Alaska, fish to school is a big deal.” Mandala agrees that different geographical locations will have their own low-hanging fruit, and it’s up to locals to find it. “You have to identify what grows well, wherever you are, and what your land situation is, and how much you need, and what kids are going to eat,” he says. With the contract in place, Mandala recently seeded more than 500 kale plants. Early summer, it turns out, is a great time to start a fall crop of kale. The seeds can be planted directly in the ground or started indoors, as Mandala did with his Red Bore and Winter Bore kale, which are the best varieties for chip-making, he says. Their extra-curly leaves grip oil and flavorings, while their high fiber (even for kale) makes for a solid crunch. Plus, the shape of the leaf lends itself to easy stripping of the leaf’s flesh from the central vein, he says. But any kale would work, and all kale is good. In addition to the chips’ pleasing taste, kale’s many health properties provide ample opportunity for creative storytelling to help entice the students. Kale is also high in calcium, and one of the best sources of vitamin K, which helps the body absorb calcium. “Most of the calcium in milk goes through your body, and most of the calcium in kale gets absorbed by your body,” he says, though he admits that the joys of calcium absorption remain a tough sell. To make Ninja Chips: The more curly the kale, the better, in terms of workability. But this recipe can be made with any kale, and even with collards, which take a bit longer because of their higher moisture. Strip the leaf flesh from the central vein and rip it into bite-size pieces. Mix them in a bowl with 1 to 3 tablespoons of olive oil (depending on the size of the bunch; you want enough to coat all surfaces) and ½ teaspoon (plus or minus) salt or garlic salt. Place the pieces on a cookie sheet (or sheets) in a single layer. Bake at 350º for 10 to 15 minutes, keeping close watch to make sure they don’t burn. “You don’t want too much brown, because browning is the start of burning. If you burn them they taste horrible,” Mandala says. Christensen, who’s become an expert on kale chips, tells me, “Thirty seconds is the difference between a perfect kale chip and a burnt kale chip.” He also cautions against using convection ovens. The leaves, he says, blow away. Once they’re out of the oven, the chips quickly cool and are ready to eat. You can toss them with any number of seasonings, from Cajun spice to garlic powder to old-fashioned salt and pepper. |

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel