|

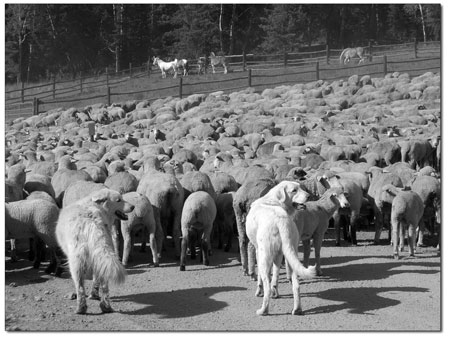

| A pair of livestock protection dogs guard a flock of sheep. Used for centuries in Europe and Asia, the dogs are just making their way to the San Juans, where they offer an alternative to killing or poisoning predators. However, the extremely protective breeds have been catching some high country users by surprise, and vice versa./Courtesy photo |

The herd mentality

Focusing on high country cohabitation between livestock dogs and recreation

by Missy Votel

They may look like overgrown yellow labs from afar, but make no mistake, these high country canines are not up for a friendly game of fetch.

They may look like overgrown yellow labs from afar, but make no mistake, these high country canines are not up for a friendly game of fetch.

Known as livestock protection dogs, or LPDs, these working dogs have been used for centuries in Europe and Asia, but are just now making their way to the San Juans. And as they become increasingly popular among sheep ranchers looking to keep predators at bay, encounters with other public lands users are becoming a concern.

Although there have been no reported incidents or direct complaints, San Juan National Forest managers are looking to head off any serious problems between hikers, bikers and other recreationists and the inherently protective breeds.

Next week, local residents will have a chance to see the dogs up close, ask questions and learn how best to behave around, or avoid all together, these latest additions to the Colorado landscape. A joint effort between the San Juan Public Lands Center and the La Plata County Wildlife Advisory Board, the “Livestock Protection Dog Forum” will take place Tues., June 12, from 3:30 - 7:30 p.m. at the La Plata County Fairgrounds.

Maureen Keilty, chairwoman of the Wildlife Advisory Board, said she was approached by Columbine District Ranger Matt Janowiak at the end of last summer to help educate the public on the dogs.

“We were starting to hear things – some rumors, some facts – of incidents with hikers, bikers and backcountry users,” said Keilty. “We recognized a problem brewing and decided to work together to make an actual demonstration so people can see these animals and understand how they’re used.”

Currently, there are 16 sheep grazing allotments with a total of 11,000 sheep (not including lambs) on nearly 237,000 acres of public lands in La Plata and San Juan counties.

All 16 permittees use LPDs, but the human-dog encounters are most prevalent north of Durango around Silverton, particularly along the heavily-used Colorado Trail.

Janowiak said LPDs have become more prevalent in recent years as the use of lethal force has fallen out of favor. “It’s become much more popular and widely used,” he said. In days of old, herders would poison coyotes and hang their carcasses as a warning sign to would-be interlopers.

More recently, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Protection Service has been called in to shoot the predators. But now, the LPDs, which range in size from 80-120 pounds, offer a nonlethal method of protecting ranchers’ investments. “It’s more effective and more in tune with nature,” said Janowiak.

Unlike dog breeds such as border collies and Australian shepherds used for herding, LPDs – typically Great Pyrenees or Anatolian Shepherds (Akbash) – bond with the sheep from puppyhood and grow to view them as one of their own.

For the most part, if a stranger unknowingly approaches sheep on foot or horseback, LPDs have time to recognize the person as nonthreatening and just watch them pass by. However, a rapidly approaching mountain biker or hiker with an unleashed dog may surprise the LPD or be perceived as a threat and be aggressively confronted. Furthermore, the fact that bikers wear helmets and their eyes are often obscured only makes the dogs more wary.

“No one has called us directly to complain, but we have heard traffic on it and seen letters to the editor,” said SJNF public information officer Ann Bond. “The number one thing we’re trying to do is to teach people how not to have something like that happen to them and how to deal with the situation.”

Keilty said the biggest problem is combating misinformation and the small town rumor mill. “There’s a lot of exaggerated stories,” she said. “One person mentions that they are using really fierce dogs and they were scared of them, and next thing you know, the story is that they were attacked.”

Keilty said before the problem escalates, “cooler heads need to prevail.” For starters, she said the purpose of the forum is not to debate whether livestock should be allowed on public lands or not, but to try to address the problem. She pointed out that the use of the LPDs is preferable to other modes of predator control, such as shooting or poisoning, which are not as socially acceptable and can backfire.

“It’s been shown that shooting coyotes is quick but not effective,” she said. “The coyote population only increases in an attempt to meet the stress levels of the populations, and it becomes a vicious cycle.”

She also noted that unlike the federal Wildlife Protection Program, LPDs incur no cost at the taxpayer expense. “We feel this is a great way to do this,” she said. “We’re not involved as taxpayers, it’s all up to the ranchers.”

And speaking of ranchers, Janowiak said they are expected to step up as well. They are being asked to keep sheep off trails except when they are moving herds and create buffer zones between herds and trails. Herders also are being asked to stay in closer contact with the dogs and not be gone for extended periods of time. “They do have to move camp or get something to eat and be away from the sheep sometimes, but it shouldn’t be longer than about eight hours,” Janowiak said.

For their part, hikers with dogs are asked to keep them on a leash or under voice control, and bikers are asked to dismount. If a LPD approaches, bikers should put the bike between them and the dog and shout “no” or tell it to “go back.” In addition, the SJNF will provide maps showing the projected movement of sheep herds and post signs at trailheads where sheep will be in the vicinity.

“I would think that a broad range of people using the high country would want to know about this,” said Keilty. “Ranchers have to have a role, too, if we’re going to try to make this work. We’re all in this together.”

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel