|

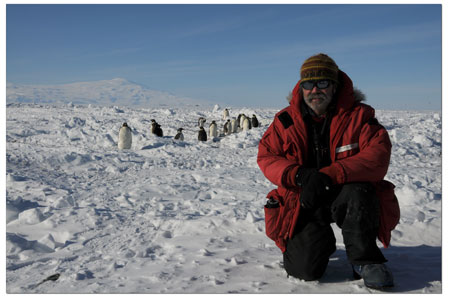

| Scot Jackson hangs out wiht some of the locals./ Courtesy photo

Southern exposureSilverton resident home away from home at South Poleby Shawna Bethell

Eleven years ago Silverton resident Scot Jackson stepped off a C-130 and onto the barren high plateau of Antarctica where the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Science Station huddles against frigid wind and shifting snow. Thinking back he laughs, “I wondered what I had gotten myself into.”

But now, after 10 seasons working at The Pole (having missed the 2009 season), Jackson considers the station his second home.

“It was tough,” said Jackson of 2009. “I really felt something was missing from me to not be there.”

For Jackson, "there" includes not just the extreme terrain and spirit of adventure that most people conjure up when thinking of the South Pole. It also includes being part of an endeavor that involves people from all over the world with myriad skills, coming together in the name of science and community.

“I was sitting in the galley having lunch a few years ago, and on one side I had two men discussing the plumbing in the new station. On the other side were two astrophysicists discussing – theoretically – how much mass is added to the earth each day based on meteorites that have fallen to the planet. I thought, ‘Where else are you going to hear these types of discussions at the same table?’" Jackson recalls.

The region beyond the 60 degree South Latitude is governed by the Antarctic Treaty, which was signed in 1959 by 12 nations. The document established parameters for Antarctica, reserving it for “peace, scientific study and international cooperation, requiring an annual exchange of information, and encouraging … environmentalism,” according to the U.S. Antarctic Program's web site.

Forty-eight countries have now signed the treaty, and current research projects at the science station cover everything from astrophysics, astronomy and global warming to aquatic life, bio-medical research and searching for neutrinos from the Big Bang that are believed to remain in the ancient 9,000 foot ice pack. And though Amundsen-Scott is a United States-based station, scientists and crew members from multiple nations collaborate in the explorations that take place there.

“Everybody’s job is important,” said Jackson who works off-loading and on-loading cargo from the six military planes that land and take off daily. “The conditions make it the best place in the world to do the science, but because of those conditions, if they didn’t have people who were willing to be there to do the support work, the science would never happen. The scientists know this and they are appreciative. Everyone is a cog in the program that allows the science to happen.”

The conditions Jackson refers to include temperatures that can reach minus 55 degrees and even a moderate wind can push wind chill as low as minus 100 degrees. There are also isolation, living in a self-contained station powered only by the rotating use of generators—of which there are three, one that is functioning, one that is being "tuned up" and one that is back-up—having access to only two two-minute showers per week, and an exhaustive work schedule. But Jackson, introduced by a friend at a recent lecture on his exploits, has been described as an “extrematerraphile.”

“I have an interest in doing things that are different,” he explained. “I’ve always been fascinated in the discovery of new things.”

Growing up in west Texas, Jackson’s elementary school teacher gave children the opportunity for free reading if they completed their work early. Jackson would finish his assignments then head for the National Geographic magazines. In the late ’50s he found one that featured the building of the first science station at the South Pole. The story stayed with him. By the ’70s, he was reading about the construction of the second station, and it was then he began thinking about wanting to work there. But it wasn’t until 2001 that it happened.

Another Silverton resident John Wright was already working at the pole, building tunnels for utility lines. He knew Jackson was interested and had skills in running heavy equipment, so after years of reading about the Amundsen-Scott station, Jackson was about to see it for himself. But he did have some doubts upon landing.

“I’ve had many adventures and lived in many places, Alaska and Africa … but the closest I can come to describing what it was like was the ice planet from 'Star Wars.' It was totally alien,” said Jackson.

When they finally established a work routine, it got easier. The station provides orientation videos for newcomers that stress the mental challenges they will face including not just the extreme weather but the nearly chaotic work regimen.

“For the whole summer, up to the time I left, I wasn’t sure that I would go back,” said Jackson. “Then, at McMurdo (the logistics hub for Antarctic science stations), we were getting ready to fly back to New Zealand. I was standing there looking out at the mountains, and I knew that I would.”

The next year, with the utility tunnels complete, Jackson started with the cargo crew. Because the station is self-contained and because of environmental impact issues, everything that is flown into the pole must be flown out, from daily waste to deconstructed sections of old stations to scientific data. And incoming flights bring equipment and supplies.

“The hardest thing is being away from here,” said Jackson, of his home in Silverton where he works for the Bureau of Land Management. “But even after 10 years, there is no downside.”

Though he attends the weekly science lectures offered at the station, Jackson says he doesn’t always understand the complexities of projects, but the sense of exploring remains with him.

“Humans have always been ‘wonderers,’" he said. “One of our distant ancestors looked up into the night sky and wondered what the stars were, and he probably walked up the nearest ridge to get a closer look. He may not have found the answer then, but what he saw over the ridge may have lead to another discovery.

“It’s the fact that we are looking, maybe finding that next thing to help human kind,” Jackson said. “That’s what science is about.”

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel