|

| Colorado Parks and Wildlife Manager Patt Dorsey gives oxygen to a desert bighorn on the lower Dolores River. Oxygen reduces the stress of handling and makes for healthier sheep. Bighorn were being captured and relocated to enhance another population of desert bighorn./Photo by Stephanie Schuler. |

Animal instincts

Wildlife manager Dorsey grabs the buck by the horns

by Stew Mosberg

Just two months into her new career, Patt Dorsey received a call at the Boulder office of the Department of Wildlife. A mountain lion had killed a deer near a school, and the school bus was due in 30 minutes. Arriving at the site, Dorsey struggled to load the half-eaten deer into her truck. It was then she became aware of the presence of the lion. Following protocol, the young DOW officer grabbed for a shotgun loaded with rubber buckshot, and as she recalls, “Hazed it in an attempt to make it more wary of places frequented by people.”

Just two months into her new career, Patt Dorsey received a call at the Boulder office of the Department of Wildlife. A mountain lion had killed a deer near a school, and the school bus was due in 30 minutes. Arriving at the site, Dorsey struggled to load the half-eaten deer into her truck. It was then she became aware of the presence of the lion. Following protocol, the young DOW officer grabbed for a shotgun loaded with rubber buckshot, and as she recalls, “Hazed it in an attempt to make it more wary of places frequented by people.”

Within a few minutes, she had attracted quite a bit of attention. “I had people shouting at me to kill the lion; I (also) had people yelling at me to leave the lion alone,” she remembers. It seems the deer was famous in the area and had become sort of a mascot to the school children.

Onlookers were crying, wondering if the deer was “Tinkerbell,” so named because of the bell tied around its neck. Television crews had also arrived adding to the drama, and it was then she remarks that Dorsey knew, “I was going to have an exciting career.”

Dorsey has worked for Colorado Parks and Wildlife, (formerly Colorado Division of Wildlife) for 21 years now and as she puts it, it is more than a career; it is a life-calling. “This is my dream job and has been since I was in 4th grade,” she said.

Born in Sterling, the native Coloradan attended CSU and earned a B.S. in wildlife biology. While she was still a youngster, her grandparents took her on a vacation that included riding the Durango & Silverton Railroad. Dorsey smiles at the thought and says, “The train whistle that I hear now, several times a day, brings me many great memories. I am so lucky!”

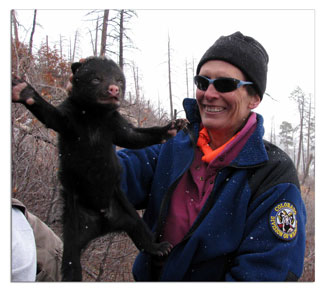

|

| Dorsey holds a bear cub for quick measurements and a health check to be used in black bear research. According to Dorsey, such scientific data gathering is the backbone of wildlife management./Photo by Lyle Willmarth |

After a six-year stint in Boulder, Dorsey was transferred to Denver for two years and was then promoted to a job in hunter education. As her expertise grew, she further progressed and was eventually bumped up to Area Wildlife Manager and moved to Durango. That was almost 10 years ago.

Although never actually attacked by an animal or human, Dorsey tells of some all-too-close encounters, some of which she says, “Made the hairs stand up on the back of my neck and also thankful and reflective when they were over.”

For the most part, she has the skills, outdoor experience and essential tools to recognize and minimize those potential dangers, yet she has taken some necessary precautions.

Dorsey recalls one incident in particular when, armed with a search warrant, she was threatened by its intended recipient, who had been previously arrested for carrying a concealed weapon. She knew the intense animal rights activist was an extremist, capable of following through on his threat. She readily admits that after that episode, she wore my bullet-proof vest everywhere for months, “even when I was alone.”

Far from being an ordinary job, the best part of Dorsey’s profession is that there are no routine work days; at any time she might be summoned to a law enforcement scene, a bear in a house, or an injured bald eagle that can’t take flight.

As a supervisor, she doesn’t get to participate in as many of those call-ins as she used to, but one such episode occurred about a year ago. Arriving at the scene, she found a large mule deer had its antlers and torso tangled in barbed wire and it was in a state of near exhaustion from battling the fence and blood had stained the snow bright red.

“I decided to cut him out of the fence rather than saw off his antlers,” she explained. Being late November, a time when deer are rutting, Dorsey was concerned that the buck might be at a distinct disadvantage without its antlers during breeding season.

“As soon as I approached him, he stood and charged me. The tips of his antlers barely missed me as I hunched over him with my fencing pliers.”

Fortunately when he lunged, one of the fence posts was still connected to the entanglement, but in the process had flipped over to where Dorsey stood. She instinctively grabbed and twisted it, drawing the wire tight, and wedged it between a tree and another post. The maneuver took the slack out of the wire and kept the buck from moving. Cautiously, Dorsey cut the wire, strand by strand, until he was finally free.

Unfortunately, the encounter didn’t end there, expecting it to run off, the animal charged her again. The fast-acting, quick-witted agent grabbed some debris lying near the deer and holding it aloft attempted to defend herself and distract the animal. The temporary diversion redirected the animal’s attention and it beat a hasty retreat and ran off.

Dorsey points out that the work done by the department is often misunderstood, and she needs to support her staff when it is forced to make an unpopular decision in the interest of public safety. Typically, this translates to putting down a conflict bear. She also coordinates with other people and agencies to make long-term decisions that she says, “Will help sustain wildlife populations into the future.” One example she gives is how the Forest Service and Colorado Parks and Wildlife work together so that fuels-reduction treatments, done to protect homes from wild fire, also have some long term wildlife benefits.

An avid outdoorswoman who also seeks creative outlets such as writing, photography and beading, Dorsey somehow still finds time to volunteer at Manna Soup Kitchen and conservation organizations. Her energy, efforts, and commitment to the environment are a guiding light not only for her colleagues and the Department, but the community at large, whether it knows it or not.

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel