|

| ||

| Blessings in disguise

by Willie Krischke

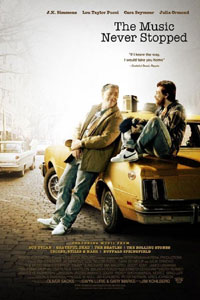

This may be why I connected so deeply with “The Music Never Stopped,” a film that’s gotten tepid reviews from most movie critics. But I wonder if those critics are looking at the movie through the wrong lens. They see another film about a creative and unorthodox therapist getting through to an otherwise unreachable patient, much like “The King’s Speech.” And while that may be the form of “The Music Never Stopped,” there is something quite different at its heart. This is a movie about finding an uncommon and mysterious grace in a tragic and terrible situation. This is Flannery O’Connor’s kind of grace, and that’s part of why this is the kind of movie I love. My daughter’s name is Flannery, after all. The film is based on an essay by the innovative neurologist Oliver Sacks, who also wrote the book Awakenings, which became a 1990 film starring Robin Williams. (I dare you to name any other neurologist who’s had two books turned into films.) Lou Taylor Pucci plays a young man who, after brain cancer that leads to radical surgery removing huge swaths of grey matter, is unable to form new memories. He spends most of his days blank, meeting the same people over and over again, never aware that he has met the cafeteria lady and hit on her every day for the last several months. The great character actor J.K. Simmons (you’ll recognize him from “Spiderman,” “Juno,” and those insurance commercials) plays Pucci’s father, in a rare turn as a lead. He is consistently great, and often saves the film from falling into maudlin sentimentality. The father and son had a terrible falling out when Pucci was 18, in the turbulent 1960s, and he left home, as so many young people did, chasing his dreams to be a musician in the Village. “The Music Never Stopped” is set in the 1980s, Pucci is in his thirties now, and his parents haven’t seen him since the day he left. Because of his brain damage, he can’t tell them where he’s been or what he’s been doing. Those years are gone forever. In his desperation to get his son back, Simmons brings in a music therapist, played by Julia Ormond, who thinks she can help. She discovers that when she plays the music he loves, he lights up and becomes his old self again. He’s smart, witty, clever, able to converse and remember, until the music stops, and then he goes back to blankness. It’s a great discovery, with only one hitch – the music Pucci loves is the Grateful Dead, the Beatles and Bob Dylan. It is the same music his father blames for stealing his son away from him.“The Music Never Stopped” does a great job of establishing early on that Simmons is just as passionate about music as his son is, only he’s passionate about the music he listened to while he was growing up and is hurt that his son doesn’t care for Bing Crosby or Frank Sinatra. As is often the case in real life, it’s what they have in common that is driving them apart, and it’s also what can bring them back together. Simmons must decide if he’s going to hang on to all of his prejudices about the music of the 1960s, as well as the culture it embodied, or if he’s going to use that same music to relate to his son. This is where “The Music Never Stopped” becomes a much more interesting movie than your typical creative therapist drama. Of course he chooses his son – that’s the predictable, sentimental part – but it’s interesting what this does. It gives him another chance to relate to his rebellious teen-ager son, to start over and, in a sense, relive those confusing years when he lost him. He’s 20 years older now, and a bit wiser and more open to things he doesn’t understand. He plays the records, music he still doesn’t understand or like, but this time, he asks his son questions. What is Bob Dylan singing about on “Tombstone Blues?” Why is The Grateful Dead your favorite band? What’s the deal with the White Album? I wonder how many parents who “lost” their kids when they were teen-agers would do things differently if they got those years back? I wonder how many parents would ask more questions, try harder to understand their kids, and spend less time judging and preaching and laying down the law? It’s a tough time, both for parents and for kids and as Simmons says, “It was a confusing time. We were all pretty confused.” He’s talking about the ’60s, but he might just as well be talking about the coming of age years between 16 and 20. I don’t know many parents or kids who make it through those years without some damage done to the relationship. Seems like generally, it takes a few years for parents and kids to grow up before they can enjoy each other again. But not all families get that chance. Some kids run off to the city and never come back. “The Music Never Stopped” is about such a family, and about the second chance they were given, through the miracle of a brain injury. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel

I have two young children, and I love music. Right now, my kids are really too young to love music with me, though I can sometimes get my 2-year-old to dance with me. I often wonder if I’ll be able to impart my love of music to my kids, and if they will love the songs that I love. My wife is pretty indifferent (outside of a few groups she connected to in college) to music, so it’s not a sure bet. What if they don’t love music with me? Or worse, what if they love music that I hate, or love music that I hate because I hate it? These may seem like silly questions to you, but they occupy an inordinate amount of my brain space.

I have two young children, and I love music. Right now, my kids are really too young to love music with me, though I can sometimes get my 2-year-old to dance with me. I often wonder if I’ll be able to impart my love of music to my kids, and if they will love the songs that I love. My wife is pretty indifferent (outside of a few groups she connected to in college) to music, so it’s not a sure bet. What if they don’t love music with me? Or worse, what if they love music that I hate, or love music that I hate because I hate it? These may seem like silly questions to you, but they occupy an inordinate amount of my brain space.