|

| ||

| Leaving the grid SideStory: The price of coal-fired power

by Leslie Swanson

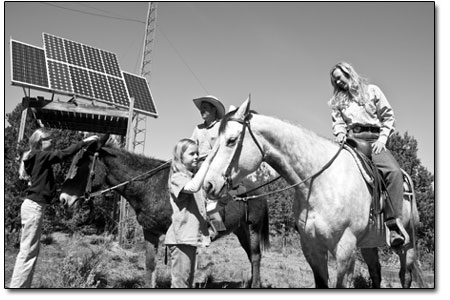

Here in Southwest Colorado, we don’t have nuclear power plants right next door. However, two nearby coal-fired power plants do emit pollutants into the local airshed 24 hours a day. Last year alone, the toxins released from the Four Corners Power Plant and the San Juan Generating Station caused 1,400 asthma attacks, 116 heart attacks and 77 deaths, according to a study endorsed by the EPA Science Advisory Board. The cost in emergency room visits and hospital admissions totaled approximately $596 million. Faced with such a price tag, many La Plata County residents are choosing to change their source and use of electricity. Some La Plata Electric Association customers purchase wind-generated electricity for a small extra fee. Others have installed “grid-tied” systems to supplement their LPEA power with solar and wind generators. And a few former customers have pulled the plug completely and gone “off-grid,” opting to trade in a measure of convenience for a cleaner environment. Art Evans, of Sunland Renewable Systems, notes that most of his customers fall into the grid-tied category, which is cheaper than stand-alone solar/wind systems and easier to install. It also allows for optional unlimited power use. Off-the-grid systems can be hard for the average household that uses a lot of electricity. “The lifestyle you lead determines if you can go off-grid,” he observed. Whether or not you use alternative power sources, cutting back on the amount of electricity you consume is a first step. One simple way to reduce your usage is to get rid of “phantom loads,” Evans advised. This can be easily accomplished by plugging appliances such as stereos, computers and TVs into a power strip and turning it off when you are finished. “If you have any appliance with a clock in it, a TV that is waiting for the remote to turn it on, a computer on standby, all these draw a lot of electricity that you might not even be aware of,” he explained. While grid-tied systems are most popular locally, some rural residents are finding off-grid solar systems to be more affordable than connecting to a distant line. Whatever their initial reason for pulling the plug, most local off-gridders will easily recommend it to anyone who can afford the start-up costs. Cheryl Albrecht-Harvey, who lives with her husband, Kennan, and 5-year-old daughter up Junction Creek, says her family has been LPEA-free for 10 years and has never missed the grid. “It is the right thing to do and the costs were close to those associated with trenching in power to our home during initial construction,” she explained. The Harvey family gets 1,400 watts from solar panels feeding into eight 24-volt DC batteries, which is then converted to 120 volt AC through an inverter. They do have a backup generator for long cloudy stretches but only turned it on six times last year. One of the biggest benefits of living off the grid, Albrecht-Harvey said, is educational. “Our five-year-old daughter never leaves a light on and she is aware that the movies she watches are powered by the sun,” she said. “She is also more aware of the sun and where it is in the sky during the summer and winter.” While Albrecht-Harvey admits that the up front costs for alternative energy systems can seem expensive, the returns are well worth it. “Unfortunately, most Americans don’t recognize the environmental costs of conventional power in the U.S., such as dirty air from coal power and nuclear power as we see in Japan right now, just to name a few,” she said. “Carbon emissions are a serious issue for future generations.” Katherine Dobson and Ted Zerrer moved into their off-grid home near Mancos a year ago. “We were looking to buy a home on land and found a house that was already set up off grid,” Dobson said. “While some people saw that as a disadvantage, we were excited about it. We are sold on being off-grid. We love it.” The Dobsons operate all the usual appliances – refrigerator, freezer, dishwasher, washing machine and miscellaneous electronics – and rarely run low on power. “We are still surprised at how little our lifestyle has had to change to be off grid,” Dobson said. “We thought we would have to live really differently, and what we’ve found is that the amount of electricity we make is amazing. By 10 a.m. most days, we are fully charged. The climate here is perfect for solar.” The one appliance the Dobsons thought they would miss was the clothes dryer, but they have since become enthusiastic clothes-line converts. Their laundry dries quicker, smells great and “it is very empowering to go dryer-free and enjoy the fresh air,” Dobson said. Chris Anderson, his wife, Julia, and two daughters live comfortably off-grid in rural western La Plata County. “It’s a mentality but not a hardship,” he said. “Our house doesn’t run any differently than any other house. We have a microwave, TV, computers, refrigerator, etc.” When the Andersons first installed their system, the electrician bet them that in five years they would be tying onto the grid. “But we’ve lived out here for 15 years, and we never said, ‘Gee, I’d like to be hooked up to the grid,’” Anderson said. “It’s not an inconvenience, it’s just a different way of thinking about power usage. When you leave a room you turn off a light. When you don’t need to use power you don’t.” This article was written on a notebook computer powered by a solar panel with charge regulator, 400 watt AC inverter and two golf cart batteries. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel

What is the hidden price of turning on a light? Japan’s recent nuclear meltdown is a reminder that electricity generation involves risks and consequences that may be far more expensive than anyone anticipated.

What is the hidden price of turning on a light? Japan’s recent nuclear meltdown is a reminder that electricity generation involves risks and consequences that may be far more expensive than anyone anticipated.