|

| ||||

| Sept. 11 revisited

by Jeff Mannix

“I dropped Kyle off at school – it was about eight o’clock – then drove Corinne to her first day of kindergarten. When I was walking Corinne up to the door, her teacher was all excited, told me that a plane had struck a building in Manhattan,” Dell said. “Lots of strange things happen in New York City, and small planes have hit high rise buildings before. It was something I had to check in on, though.” Dell went directly home, turned on the television, and about the same time his cell phone rang. “Every one of New York’s 10,000 firemen was called to duty that Tuesday,” Dell explained, “and I was at the 73 about 20 minutes after the second Tower had been hit.” The ladder truck from Engine 73’s companion station in the same building had already left for Manhattan. Dell and 15 or so firemen piled in the cab, on the roof hose-bed and along the running boards. “Engine 73 was dispatched to the WTC with as many firefighters as it could hold, and about 50 of us commandeered a city bus outside, threw off the passengers and ordered the driver to put his foot to the floor,” Dell recounted. “We arrived before the buildings collapsed, parked the bus in the rubble as close as we could get, then headed for the fires in only our turnout gear – no breathing apparatus, no tools, without command because our radios were just making noise and we didn’t know where Engine 73 was.”

The South Bronx and adjacent Harlem are the epicenters of New York City’s everyday bad news. Dell’s engine company answers between 15 and 20 calls a day, doing some 4,200 runs every year. Dell was already a hardened firefighter at age 29, after three years at Engine 73 Company, and earned his stripes as a “proby” among the senior men and officers. He had been into burning high rises, heard the screaming, dodged bullets, put his life on the line and already embodied the dedication of every NYC firefighter since 1865. So when he arrived at the conflagration that was the World Trade Center – two buildings 110 stories tall – he was with his unit but without resources, including radio communication, which the New York City Fire Department was to admit inadequate to nonexistent later in their debriefing analysis. “We got out of the bus and saw something like we’d never seen before,” Dell confessed with widening eyes. “We knew our job was to find survivors first off, especially firefighters that we knew. But we didn’t have tools – no axes, no poles, no pry bars, nothing but our bare hands – everything, even our gloves, were on the engine and the smoke and dust was so thick we couldn’t see nothing,” he said. “We saw a ConEd truck on the street with nobody in it, so we picked up pieces of iron and broke into its tool boxes and got lucky to find some tools we could at least begin digging with." Dell and his unit worked their way through the ruins toward Building 7, the third skyscraper to be reduced to rubble on Sept. 11. The shorter, 30-story skyscraper was engulfed in flames, and other firefighters were already evacuating when they got down to the lobby. At that point, Dell and his unit started to receive intermittent information through their radios that the building was about to collapse. “We turned around and by the time I got back to safe ground I couldn’t breathe and was coughing so hard that I could hardly walk, inhaling more dust and smoke with each cough,” Dell related. He was taken to a makeshift triage center in the lobby of one of the unscathed nearby buildings, then transported to a hospital with what would later prove to be serious lung damage that would end his career with FDNY three years later. “By the time I got out of the emergency room, up to a hospital ward, I was feeling better, but I knew I didn’t have the strength to leave and go back to work with my unit,” Dell reflected. “But the next morning, before dawn, I felt a whole lot better, put my gear on, checked myself out of the hospital and flagged down a cop car and ordered him to drive me back to my firehouse. When I got back to the 73, I learned that four of our guys were missing, the unit on duty that responded first.” By now, 24 hours later, the 73 was vibrating with life, tension and the pride of duty. “All the retired guys were there, about 30 people were sleeping everywhere, fixing gear, cooking food and getting ready to start a new shift in the district and back at the towers,” Dell said. “I didn’t go home for four or five days, pulling my regular shift then going down to the towers to look for our missing guys. We were close, all the guys at 73, we worked as a team, knew each other better than we knew our family. We were a family, and we had a job to do, and we had to find our missing guys.” After a week, command was established in lower Manhattan and throughout the FDNY system. Shifts at all 200 firehouses had to be covered, after which firefighters would go down to the World Trade Center to pick through the 1.5 million tons of debris. The first tower stood for 56 minutes after it was struck, the second tower for 122 minutes. It took only 22 seconds for them to collapse. On that day, 2,819 people perished, including 343 New York City firemen. “We were living in a bubble the next nine months,” Dell explained, “working all the time and going to funerals on our forced days off – at first, 20 a day. We always had a full bagpipes band at every line-of-duty funeral, but there were so many funerals after then that we’d only have one bagpiper at them. But with every body part we’d find at Ground Zero, we’d bag it and place it in a stokes basket covered with an American flag, stand honor guard until a fire truck could transport it through a cordon of firemen and construction workers, paying our respects.” New York City, with a population of 8 million, doesn’t stop having fires and medical emergencies just because firemen and medics are needed elsewhere. Engine 73 still made 15 to 20 runs every day; EMTs still answered medical emergencies; sirens could still be heard in every quadrant of the Big Apple day and night. But the city was changed after Sept. 11, 2001. Three times as many firefighters retired in the year following than the year preceding; a half-million New Yorkers were treated for post traumatic stress disorder; and Dell Truax would be hospitalized three more times over the next three years. He convalesced first for six months, then for 10 months and then for a full year before doctors refused to assign him back to duty. His coughing eventually abated, but the humidity of the East Coast held a grip on his breathing. Dell and his family made the move to Durango in August of last year. And though he will always be a fireman first class of Engine 73 in South Bronx, he doesn’t tell his story; it had to be pried out of him. He doesn’t feel the hero. “I’m a fireman in the largest and greatest fire department in the world,” Dell espoused. “We have an old culture of duty; I did my job.”

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel

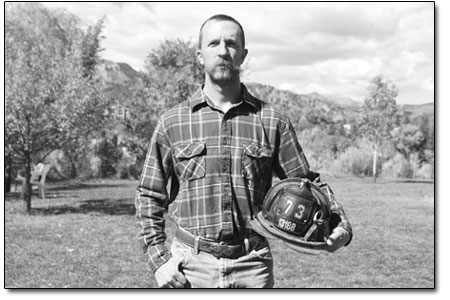

Now a Durango resident, Dell Truax is a fireman in Engine 73 Fire House in South Bronx, one of the five boroughs making up the 322 square miles of New York City. He grew up and lived with his wife and two young children in Yaphank, Long Island, 70 miles from the City. Dell is a family man, both he and his wife Maureen come from close knit families. On a beautiful, sunny day in September, Dell took the day off to bring his second-grade son and kindergarten-aged daughter to their first day of a new school year. The date was Sept. 11, 2001. His life and the life of his family would never be the same.

Now a Durango resident, Dell Truax is a fireman in Engine 73 Fire House in South Bronx, one of the five boroughs making up the 322 square miles of New York City. He grew up and lived with his wife and two young children in Yaphank, Long Island, 70 miles from the City. Dell is a family man, both he and his wife Maureen come from close knit families. On a beautiful, sunny day in September, Dell took the day off to bring his second-grade son and kindergarten-aged daughter to their first day of a new school year. The date was Sept. 11, 2001. His life and the life of his family would never be the same.