|

| ||||

| Working in harmony

by Shawna Bethell

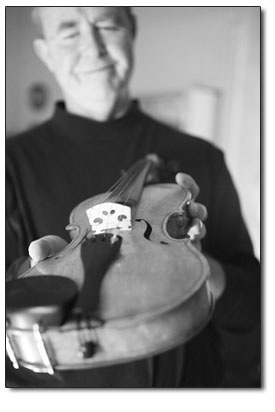

“They didn’t even know the most common music language,” White adds, and it was a wake-up call for the educator. The encounter was not that long after a time when the Silverton School had an award-winning band and choir, a traveling choir and student musicians who went on to become professional players. But when the mine closed, there was an “exodus” from Silverton and there were no longer enough students for a band, the teacher left and the program died. Some remaining teachers tried to incorporate lessons about music into their existing lesson plans, but Over the next couple of years, White hired part-time teachers to come in a couple times a week and provide a semi-structured music curriculum. There was no hope of reintegrating a band or choir, but there was hope of helping individual students with a desire to learn and perhaps form trios or quartets to play together. “Music can become a lifelong love,” White says. “If students are exposed early, it can stay with them throughout their lives.” She also feels that the lesson of persistence is an invaluable life lesson. Apparently, the community of Silverton feels the same. As viable options for a music program floundered, community volunteers stepped forward in myriad ways to bring the program to life. A local geologist/gift shop owner stepped forward to teach students to play drums. The town clerk stepped up and is offering lessons in guitar. And one man is building a cello to donate to student musicians.4 Black, a music lover from the tender age of 4 and an accomplished player of multiple instruments – both string and brass – is a self-taught luthier. In 2009, he rebuilt a violin that he gave to the school, and this year he decided to tackle building a cello. But materials are expensive, so Black put a call out to the community. Much like it did for the school’s program, music-loving Silvertonians stepped forward. “This is a real community cello,” Black says. A portion of the back of the cello is laminated wood donated from Venture Snowboards, and the drawer front of a 130-year-old dresser may find its way to the inner lining. Residents of the Benson boarding house – where Black lives and builds his instruments – donated money, and others in town have donated some sweat equity.

A portion of the back of the cello is laminated wood donated from Venture Snowboards, and the drawer front of a 130-year-old dresser may find its way to the inner lining. Residents of the Benson boarding house – where Black lives and builds his instruments – donated money, and others in town have donated some sweat equity. “Donated wood is an experiment in time and monitoring,” said Black. “Wood that doesn’t work can become a mold for instruments or I make it into tools such as clamps.” Black has written letters to the editor in the Silverton Standard to keep the community informed of his progress. He also has an account at Flickr where photos are posted. Slowly, the Silverton School music program is gaining ground. The Booster Club purchased mountain dulcimer kits for the kids, who after building the instruments were able to master them for a performance. And during the summer, volunteers put together a fund-raiser where Silverton musicians joined together and played to a sold-out crowd. Ironically, one of the biggest obstacles comes not from local challenges, but the federal government’s No Child Left Behind. The guideline says that for a school to be in compliance, a music program must have a teacher who has a Colorado teaching license and is considered to be a “highly qualified teacher.” But there is no money for a full-time music teacher in Silverton, and few experts would be willing to relocate to a remote mountain community for part-time wages. And though there are many talented musicians and singers living in the community, none are “highly qualified” by governmental standards. “Each year it’s an ordeal,” says White. “The options are to have no program and be in compliance or to have the volunteer program and face possible penalties.” But White feels the risk is worth it. “There are studies that show that kids who are involved in music are linked with higher intellectual growth,” she says. “It’s an inherent loss if our kids aren’t exposed to music.” This year is tough for the school as it is undergoing remodeling, but the new plans were drawn with the vision of a music program. “Our kids are slowly reabsorbing the vocabulary, and we’ve even had some of them on stage performing,” White reflects. “We may not be traditional, but we’re keeping the avenue open amidst our challenges.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel

"I remember standing at the back of the room thinking, ‘This isn’t fair,’” recalls Kim White, superintendent and principal of Silverton School. It was two years ago, and the Central City Opera was making an unexpected visit to the little burg. After the performance, the players had a question-and-answer segment with the kids, who drew blanks on nearly everything the players asked.

"I remember standing at the back of the room thinking, ‘This isn’t fair,’” recalls Kim White, superintendent and principal of Silverton School. It was two years ago, and the Central City Opera was making an unexpected visit to the little burg. After the performance, the players had a question-and-answer segment with the kids, who drew blanks on nearly everything the players asked.