|

| ||

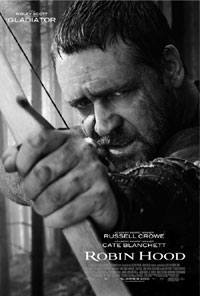

| A merry miscast

by Willie Krischke Robin Hood” is a fine movie. It’s big and fun and full of swash and buckle; it’s full of the stuff summer entertainment is supposed to be filled with. The only problems I have with it are its title and entire premise. Russell Crowe, that great hulk of decency and duty, plays a soldier in King Richard’s army. It is the end of the Third Crusade, they’ve been to Jerusalem and are on their way home to England, sacking and plundering as they go. Danny Huston plays Richard as a king who was once great, but has no illusions about what he has become. Soldiers (and their families) tend to think better of their commander-in-chief at the beginning of a Crusade than at the end. He seems to be hoping he will die before he returns to England and must deal with an impoverished, war-torn country in peacetime. Suddenly that wish is granted – he is killed by a lucky cook with a crossbow. Crowe finds himself impersonating a knight and escorting the crown back to Richard’s poor mother (Eileen Atkins) and psychotic brother, the new King John (Oscar Isaac, who is clearly taking his cues from Joaquin Phoenix’s performance in “Gladiator.” That’s not a bad thing.) Crowe must also carry a dying man’s sword back to his father. Come to think of it, he spends most of the movie doing favors for other people and pretending to be people he is not. Max Von Sydow is the bereaved father, Sir Robert Loxley of Nottingham. One can’t help but remember another knight Von Sydow played in a very different movie. Cate Blanchett is Loxley’s daughter-in-law, now a widow, but that’s a fact they’d rather keep secret, so Crowe is entreated to impersonate her husband. Blanchett is a hard woman; her days are spent fighting off orphan marauders who live in the woods and begging/haranguing the local parish to let the villagers use the church’s seed to plant their fields. She threatens to cut off Crowe’s tender parts. Times are tough in Nottingham, and elsewhere. To make matters worse, King John has a traitor for a best friend. Mark Strong, playing his third villain in the last five months (he was the mobster in “Kick-Ass” and the sorcerer in “Sherlock Holmes”) is in league with the King of France, who looks an awful lot like the King of England. Strong stirs up dissension amongst the king’s noblemen, burning villages and storming castles when they can’t pay their taxes. A rebellion is brewing, which is music to the ears of the French. Now Crowe finds himself tasked with unifying England and fighting off the French, with the Magna Carta in hand, and the help of his merry men and the guidance of William Hurt, who plays the wise and shrewd William Marshall. I think we could all use the guidance of William Hurt from time to time. This is all well and good. It makes for an entertaining sword-and-horses story, a successful breeding of “Lord of the Rings” and “Gladiator.” Director Ridley Scott is remarkably competent at handling multiple characters and storylines. The plot of “Robin Hood” is unusually complex for a summer blockbuster, but never loses its way. He also, famously, handles epic battle scenes well, and the ones in “Robin Hood” are clear and violently poetic. As in “Gladiator” (also directed by Scott) and “Braveheart,” the dialogue is littered with lightly veiled references to democracy and human rights, making an archaic culture and political system feel progressive and modern. There’s not much chemistry between Blanchett and Crowe, and their romance didn’t really work for me, but that’s a small beef for a movie like this. It’s an action/adventure flick, not a romantic comedy. The problem is that, in my mind, this isn’t a Robin Hood story. The Robin Hood legend is as old as the hills, and its best depictions (and there have been many) onscreen and in literature always have one thing in common: they depict Robin and his merry men as, well, merry. This is not superfluous to the story; it makes the story unique. The heart of the Robin Hood legend is that there is joy in fighting injustice, and there is beauty in speaking truth to power and cheer in caring for the poor and the oppressed. In the best tellings, Robin takes life-and-death risks with an unmistakable sense of gaiety and fun, perhaps knowing that even if he dies, he wins in the end. The twinkle in Robin’s eye is what sets him apart from a hundred other heroes. This element is completely missing from Ridley Scott and Russell Crowe’s “Robin Hood.” I’m trying to remember a single moment in this film when Crowe cracks a smile. There aren’t many. He goes about his business dutifully, honorably, but not joyfully. He is always carrying a heavy burden, and it weighs on him. Crowe is an actor of great gravity and quiet dignity, and he is never playful or merry. It’s not just that there is no twinkle in his eye; it’s that it’s hard to imagine that twinkle ever being there. Russell Crowe makes a great medieval warrior but is horribly miscast as the Robin Hood of legend and song. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel