|

| ||

| A noble calling

by Jeff Mannix

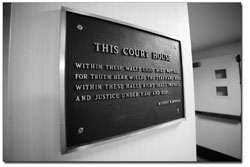

That attorney will be a public defender. He or she is easy to spot: dark rings under the eyes in a rumpled, drip-dry suit, a stack of file folders under one elbow. In Colorado, there are 300 such criminal defense trial attorneys as well as 30 appellate attorneys, all working for the Office of the State Public Defender scattered among 22 judicial districts. The Durango Office of the State Public Defender was one of four original regional offices established in 1963. Public defenders are available for people whose income falls below the poverty level or persons who are denied or cannot afford bail. The Durango Office of the State Public Defender is staffed by seven defense attorneys covering five counties – La Plata, Archuleta, San Juan, Montezuma, Dolores – and handles 150 to 200 cases monthly. The office is currently involved in 700 active cases, and each attorney’s average workweek is 60 hours but can easily surpass 80. The lawyers are paid a salary unrelated to the cases handled and the hours spent, but they are “workaholic adrenaline junkies,” as one of them confesses. Justin Bogan has been a public defender for eight years and is the manager of the Durango Office of the State Public Defender, which means that he works his own caseload and consults on every case handled in his office. “The public defender sets the standard for criminal defense,” he says with pride. “We are the oversight for incomplete or erroneous prosecution throughout the criminal justice system, and, in a direct way, assure that every citizen in the U.S. has equal protection afforded in the Constitution and Bill of Rights. If we don’t or can’t defend the poor and downtrodden, everyone is at risk of losing freedom.” Ninety percent of criminal defendants qualify for public defender counsel, but only 5 to 10 percent actually go to trial. The rest are either dismissed or plea bargained to avoid mandatory minimum sentences. “The system is not set up for the defense to win,” says Douglas K. Wilson, Colorado State Public Defender. “If we had a level playing field, defense counsel would have all the investigatory resources that police, prosecutors and the courts have, but we don’t. We start with an arrest report, that’s all, and a client who has most likely been snared by the system before and doesn’t look so good on paper.” However, Wilson is quick to continue, “Nobody is born bad. They are taught to make bad choices, which is a failure of our culture, and once they get into the system, their reputation will follow them forever, and they get no benefit of doubt.” John Baxter always wanted to be a public defender. He graduated law school in 2000, interned in the Adams County public defender’s office, then worked as a public defender in Adams and Denver counties, handling 300 cases in one year. He came to Durango in 2002 when a position opened. Havinge worked in Durango for five years, he closed out 1,000 cases before he was offered the “job of a lifetime” as a war crimes prosecutor in The Hague, Netherlands. “I just couldn’t turn that job down – the salary, living abroad, the prestige,” he says. However, after a year, things turned sour. “I couldn’t do it anymore. I couldn’t overlook the ugliness, the pretense of prosecution. It wasn’t what I became a lawyer to do.” Baxter is now back in Durango and incubating a private practice, mostly civil law – the bread and butter for lawyers – and picking up the occasional spillover case from the public defender’s office to keep his hand in criminal defense and enjoy the adrenaline rush that all public defenders seem to be addicted to. “I hated quitting my job as public defender,” Baxter says remorsefully. “It is a noble calling, defending those who don’t have the means to defend themselves. But I have a wife and three kids, one with special needs, and I just couldn’t make ends meet on a public defender’s salary.” Nonetheless, Baxter hopes to get back into public defense someday. “Being a public defender and fighting for the little guy, the guy who’s easily swept aside and put away because he was born on the wrong side of the tracks, is pure,” he says. “It’s the purest of any work I know.” Chris Trimble is another young, former public defender who overdosed on public defense for five years and is taking a break to get his heartbeat back to normal. “The public defender is the only one in the criminal justice system who doesn’t pursue selfish goals,” Trimble exclaims, his eyes aglow. “He is underpaid, overworked, never thanked, and his future is more of the present. I loved it. “We’re body guards,” he continues. “The criminal justice system is incredibly sophisticated and complex, and it is so easy for prosecution to chew someone up beyond repair.” Trimble resigned from the public defender office because of mounting then overwhelming family tribulations. “My parents needed help, and I could barely find the time to phone them,” he relates. “All I did was work and more work, and it was consuming me, willfully. But this was the best job I’ve ever had, and unless I go back – and I’d like to someday – I don’t expect anything better as a lawyer.” The public defender’s job is to humanize the life of defendants – before the bench, in the eyes of a jury, under the scorching light of law enforcement – with only the shield of The Constitution to deflect the ardor of prosecutors and shade the perspective of inconvenienced juries. Todd Risberg, District Attorney in the Colorado Sixth Judicial District which includes Durango, should cringe at the sight of public defenders. However the prosecutor does not. “Public defenders are some of the most experienced defense attorneys anywhere,” Risberg offers. “They hold the government to its obligations. They do damage control.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel

"You have the right to remain silent … You have the right to speak to an attorney, and to have an attorney present during any questioning. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided for you at government expense … .”

"You have the right to remain silent … You have the right to speak to an attorney, and to have an attorney present during any questioning. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided for you at government expense … .”