|

| ||||

| Options for ownership

by Leslie Swanson

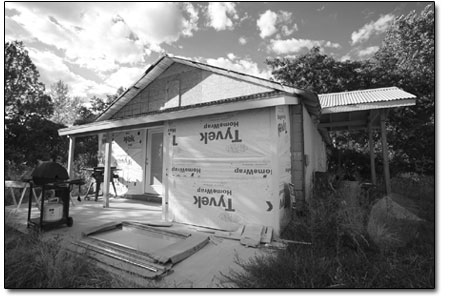

but, since the Boomers started tightening their belts, we have been left with the fine homes they did not buy, awash in a sea of granite countertops and hardwood floors. However, the disparity in price between these custom products and the budgets of local, working people is still too wide, so the empty houses sit on the market and many locals keep paying rent. La Plata County’s official response to the discrepancy is the Regional Housing Alliance. The RHA works with both city and county governments to help aspiring homeowners. They provide education, consultation and some financial assistance, mainly in the form of second mortgage loans. Since its formation six years ago, the RHA has helped 87 families buy homes. One of the alliance’s least expensive options involves a USDA loan and participation in Colorado Housing’s “Self-Help” program, in exchange for a $150,000 Bayfield dwelling. But for those who cannot get much of a loan, if any, or for those who don’t want to fritter their money away on interest, there is another strategy. Motivated residents are doing it every day, and they are doing it on their own. Courtney Krueger and Jesse Roseberry bought their 700-square-foot in-town home in July 2009 for $140,000. Their goal was to write the lowest monthly mortgage check possible. Courtney, a county employee, and Jesse, a plumbing and heating contractor, decided they would rather enjoy life than worry about a hefty mortgage. “Save enough for a big down-payment” Roseberry suggested. “Buy a small, reasonable house. You might like it when you buy it, or you can fix it up.” Upon moving in, Jesse and Courtney decided to do a LOT of fixing up. They laid their own in-floor heating, poured a new concrete floor, made countertops, tiled the kitchen, redid the bathroom plumbing and built a deck. Adding solar hot water is the next step in their renovations. Jesse estimated that the house is now worth well more than $200,000. One of the strategies that saved them the most money was to draft family members for free labor. Buying supplies from local dealers was also a money-saver, as extras could be returned for credit. “Planning is the biggest thing,” Roseberry noted. “Pick out your fixtures, cabinets, lighting first and measure everything. Then you’re faster at getting it done because you know what you’re doing.” When asked if they want to do any future upgrades, they shook their heads. “We like to get away on the weekends and have fun,” Krueger replied. Holly Rankin saw the writing on the wall in 2006, when she sold her home and bought The Bean Farm, an unspectacular house and rundown outbuildings on 45 acres. Thanks to its rural location and disrepair, it was a deal at $250,000, and Rankin was able to bypass a mortgage.

“I’m not paying rent to the bank,” she explained. Rankin, a building inspector by trade, took on the restoration herself. “The place was disgusting. ‘What were you thinking?!’ my friends said. They called it ‘Holly’s Folly’ and ‘Decrepit Corners.’ But now they’re impressed.” Among other things, Holly repaired the water system and ran electricity to all the outbuildings. Then she added extra amenities such as a hot tub with corrugated steel privacy fence, doubly useful when the neighbor is shooting rabbits. She also created a garden with raised beds of recycled concrete block (purchased for $50 at a demolition sale). The barn and garage, once repaired, were able to house all the bargain-priced items she collected for her improvements, including windows, flooring, roofing and a heating system. “We went to the Habitat for Humanity yard sale and found roof shingles. The color wasn’t right until I saw they were a dollar a bundle, then the color looked just fine.” Her advice to other D.I.Y. home buyers? “Get a good back brace and a tractor,” Rankin said. Artists Rebecca Pope and Peter Karner live in a yurt halfway to Mancos by Cherry Creek. Someday they would like to build a more solid and spacious house, but for now the yurt will do. While peaceful and close to nature, yurt living has its challenges: heating, cooling, privacy and social stigma. Insurance for yurts is hard to find ... and mortgage loans? Pope shrugged, “You’re not going to get a lot of understanding from a bank.” Dealing with La Plata County can also be a challenge. After their application for residential status, the Assessor’s Office determined that Peter and Rebecca’s home is “vacant land” - with its higher tax rate. “They said we haven’t been doing anything with that land,” Pope explained. “They don’t understand that it’s an alternative way of living. They’ll see you as squatting or transient or just ‘playing house.’” Is it worth it? “Yes. The low overhead allows us not to worry about money,” Pope said. “It frees up your time to do what’s important to you.” Shawn Ray Ferrel wants to own a home, and he and his wife have been saving for a down payment. They would like to live in town, but the mortgage would be up to three times their current rent. $200,000 is their top dollar, Ferell admits, although $100,000 would be more comfortable. On the up side, once they realized they would have to find a rural home, Ferrel and his wife reconsidered their vision. “We realized we could grow food, have animals and be self-sustaining,” he said. “We could build a more ecological home. Our labor would be our dollars.” They are considering first buying land, then building on it with the help of friends and family. Like many La Plata County residents of average means, creativity will be their top tool. “One way or another, we’ll make it happen.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel

Affordable housing. La Plata County’s long-standing lack of it keeps home ownership out of reach for most average-income residents. It’s a reality of Durango life, fueled by the fact that well-heeled people like to vacation and retire here. So developers built nice houses, and the Baby Boomers bought them.

Affordable housing. La Plata County’s long-standing lack of it keeps home ownership out of reach for most average-income residents. It’s a reality of Durango life, fueled by the fact that well-heeled people like to vacation and retire here. So developers built nice houses, and the Baby Boomers bought them.