|

| ||||

| The invasion of the San Juans SideStory: Resarchers uncover 'sonic bullets'

by Will Sands

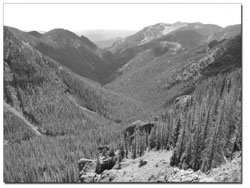

“It’s really pretty incredible,” said Steve Hartvigsen, supervisory forester for the San Juan National Forest. “You and I are witnessing the biggest spruce beetle epidemic in Colorado’s history.” While the spruce beetle (Dendroctonus rufipennis) is a North American native, it is also the most significant natural enemy of mature spruce trees. Outbreaks have caused extensive spruce death everywhere from Alaska to Arizona, and the bugs started feeding on local trees nearly six years ago. Following a recent aerial survey, the Forest Service estimated that beetles killed more than 70,000 Englemann and blue spruce last year alone. Unlike its cousin the mountain pine beetle, which has laid waste to millions of acres of lodgepole pine in northern Colorado, the spruce beetle has taken a more subtle approach to devouring local stands. “It’s not always obvious to the naked eye,” said Hartvigsen. “Spruce beetle has the longest life cycle of our beetles, and it has taken them the longest time to get going.” Though thousands of bugs will attack a single tree, the needles do not usually fade or discolor within the first year following attack. When the needles do eventually fall, the trees often still appear to be living. “People continue to see green even though the tree is dead,” Hartvigsen said. “As a result, spruce beetle outbreaks tend to sneak up on communities.” And the epidemic will continue to sneak up as it spreads west from Wolf Creek Pass and through the San Juan Mountains. Beetles have already been spotted in the headwaters of the Pine River and promise to make their way as far as Durango Mountain Resort and the Hermosa Creek watershed. For the time being, Hartvigsen noted that the beetles are steadily making their way deeper into the Weminuche Wilderness, a fact that hinders any mechanized attempts to control their spread. “For the most part, we’re sitting back and watching,” Hartvigsen said. “Most of our spruce on the east end of the forest is in the Weminuche, and a lot of it is out of Creek Pass and through the San Juan Mountains. Beetles have already been spotted in the headwaters of the Pine River and promise to make their way as far as Durango Mountain Resort and the Hermosa Creek watershed. For the time being, Hartvigsen noted that the beetles are steadily making their way deeper into the Weminuche Wilderness, a fact that hinders any mechanized attempts to control their spread. “For the most part, we’re sitting back and watching,” Hartvigsen said. “Most of our spruce on the east end of the forest is in the Weminuche, and a lot of it is out of reach. For Wolf Creek, we fully admit that there are so many beetles we won’t be able to stop the epidemic.

Foresters are not completely throwing up their hands, however. Buoyed by $2 million in federal funding, the San Juan National Forest hopes to undertake an experimental approach to controlling the bugs – a trap tree program. “Spruce beetles actually prefer downed timber and thrive in the cool, moist environments,” Hartvigsen said. “Both wind and avalanche have been significant factors in recent years and helped create ideal habitat for the bugs.” With the trap tree program, the Forest Service would drop green trees prior to the spruce beetles flight in early summer. The agency would then remove the “bait” with the beetles intact, prior to the next year’s summer. Hartvigsen said the Forest Service plans to conduct a public scoping of the procedure in coming weeks. There are a few silver linings in the beetles’ nest, however. Englemann and blue spruce are not particularly prone to wildfire and rarely burn even when dead. In addition, the beetles are currently headed for the inhospitable terrain of the Needles and Grenadiers inside the Weminuche. Stands of spruce at those higher elevations are not contiguous, a fact that promises to slow the beetles spread. Ryan Demmy Bidwell, executive director of the conservation group Colorado Wild, noted that the landscape may be the only effective deterrent against the beetles’ spread. “There’s no evidence whatsoever that you can manage forests to reduce the incidence of spruce beetles,” he said. “The beetle ebbs and flows as a natural effect of climate and forest conditions. Like it or not, it’s an issue we’ll all have to deal with.” The current health of the San Juan National Forest will be paramount in coming years, according to both Hartvigsen and Bidwell. Many the area’s stands contain a mixture of spruce and fir and will be less prone to widespread destruction. And in Bidwell’s mind, the current spruce beetle infestation is another step on the road to a more complex and hardy forest. “The latest science seems to suggest that insects are common disturbances and part of creating diversity in forests,” he said. “This is the way forests have evolved over time. The fact is this is a native insect and a natural process.” Hartvigsen agreed, but noted that this natural process could leave a lasting mark on the local landscape. “If we lose that overstory of spruce, it could take hundreds of years to get back to where we were in the forest just a decade ago,” he said. “If this thing really runs its course, we estimate the forest won’t recover for at least 600 years.”

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel

Millions of unwelcome guests are moving into Southwest Colorado’s forests, and they’re hungry. Spruce beetle infestation has reached epidemic proportions locally, and the “hot spot” is actively spreading from Wolf Creek Pass toward Durango.

Millions of unwelcome guests are moving into Southwest Colorado’s forests, and they’re hungry. Spruce beetle infestation has reached epidemic proportions locally, and the “hot spot” is actively spreading from Wolf Creek Pass toward Durango.