|

| ||

| A master work

by Joe Foster

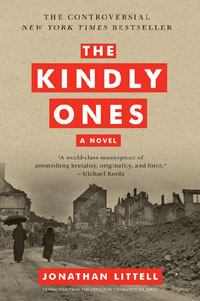

One of the most well-read people I’ve ever known resides here in the Durango area. The quintessential cowboy-gentleman, he has a host of Ivy League degrees, an enormous library and one of the most impressive mustaches I’ve ever seen. With little patience for anything he wouldn’t consider truly “great,” he reads little in the way of fiction but is constantly reading reviews looking for that next great book. Over the years, we’ve had incredible conversations about literature and history, and I spend half of these talks trying to pretend like I’m intelligent and erudite enough to keep up. So, when this gentleman told me that Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones was the greatest novel since Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, I knew that I had to tackle it. In short, my friend was right: it’s a work of genius. Almost a thousand pages of history, context and one of the most unique studies of morality I’ve come across, The Kindly Ones will repeatedly open your skull and pound your brains to mush. But what is it about? This is where I hesitate, knowing full well that should I say this wrong, I could come off looking evil, and it is here that the brilliance of this book comes to light. Named by The Times of London as one of the “100 Best Books of the Decade,” and with a mountain of similar accolades to back it up, the premise behind this book is disgusting to a rational and aware human being. Essentially, The Kindly Ones is told from the point of view of an old man looking back on his life, wanting desperately to tell his story. He has seen that over the course of the decades following this story he and his friends and colleagues have become the new standard to demonstrate just how evil humanity can be. This man, Dr. Maximilien Aue, was a Nazi and for much of World War II worked directly with Adolph Eichmann, that capable but otherwise unimpressive bureaucrat who helped engineer the Holocaust. Why in the world would anyone want to read this, you ask? Because of this: Very few people are evil, but very many people throughout history have done evil things. Most of these evil-doers truly thought (think) that they are working for the greater good, and this, this horrifying misconception (or fundamentally skewed perception of the world), is quite possibly one of the most important things for the rest of us to try to understand. Also, consider this: very possibly, the good that you aim to do is possibly seen as evil in the eyes of other people. I don’t think anyone, well anyone I know, would disagree that the Holocaust was anything but evil, but who is to blame for this evil? The leaders, the soldiers, the efficient bureaucrats, the hands that pulled each and every trigger, maybe even the townspeople who blatantly ignored the smell coming from Auschwitz? I beg of you not to see this book or this review as any kind of denial of the horrors of what happened all those years ago, but an attempt to understand it, indeed, to bring it to a new horrifying light. If we don’t understand how such things could happen we may very well be in jeopardy of seeing them happen again. Indeed, genocide very much exists today, and we, humanity, don’t really do a whole lot about it, do we? The genius, really, behind this book, is that Littell created a character of such depth and such humanity that we are forced to consider these larger questions in the context of his individual life and struggles. Aue is a severely damaged man who suffers from a childhood love so great and so consuming that he has effectively shut off any recognition of emotion until the question of this love is resolved. It’s who he loved and how they loved that twists our guts. We watch him as a young man, striving to learn, to do some great work with his youthful passion. We see those in power who harness this passion and ability to carry their own work forward. We see this inexplicable hatred for anything other than German blood, and we see this hatred carried forward by an entire people. We watch as Aue begins to understand what is happening in the forests, we then see him participate, because he is suddenly in charge and must do what he is told, and then we see him striving to help his people win a war he irrelevantly may not even believe in. Through it all, we also watch as his humanity disappears, as he tries to swallow his revulsion for these acts so that he can simply exist and care. There is an irresistible current that carries him and his people into infamy and he does admittedly little to combat it. It’s a brick of a book, but one well worth the effort. How many books have you read lately that left you wondering how the unanswered questions it raises can ever be resolved. In fact, The Kindly Ones left me feeling that answering its questions may be one of the most important things humanity can do. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel

Sometimes, as the temperature starts to drop, the peaks rise stark and white, and cooks start thinking crockpot thoughts. Sometimes what we really need is a fire, a blanket, a warm beverage and a meaty and thoughtful tome to sink into. People often speak of Summer reads, those light and fun books that help to while away the time. I disagree with the idea that we read differently in the warm months, but there really is something to be said for hunkering down with something of weight in the dark months.

Sometimes, as the temperature starts to drop, the peaks rise stark and white, and cooks start thinking crockpot thoughts. Sometimes what we really need is a fire, a blanket, a warm beverage and a meaty and thoughtful tome to sink into. People often speak of Summer reads, those light and fun books that help to while away the time. I disagree with the idea that we read differently in the warm months, but there really is something to be said for hunkering down with something of weight in the dark months.