|

| ||||

| The death of Desert Rock? SideStory: The next targets

by Will Sands

In recent years, Sithe Global has worked to bring the 1,500-megawatt Desert Rock into existence on Navajo land just southwest of Farmington. As originally proposed, the $3.6 billion plant would have been among the largest in the nation and provide electricity for 1.5 million customers in the West’s large, urban areas. In the summer of 2008, the waning days of the Bush Administration, Desert Rock gained approval from the Environmental Protection Agency, which touted the plant as “state-of-the-art.” However, opponents saw a great deal of smoke and mirrors in the approval. According to Sithe Global’s own estimates, Desert Rock would emit 12.7 million tons of carbon dioxide a year into the Four Corners airshed, and appeals alleged that the EPA’s permit was rushed through without a proper review. Last fall, the Obama EPA reconsidered the plant’s “state-of-the-art” status and officially revoked the permit citing numerous deficiencies in the analysis. Two months later, Desert Rock slammed into another roadblock when the Department of Energy denied a Desert Rock application for $451 million in stimulus funding. The taxpayer dollars would have gone to adding a carbon-capture component to the proposed plant. Despite these setbacks, Sithe pledged to “explore possibilities” and “leave everything on the table.” However, Desert Rock may be breathing its final gasp. Funding for the massive power plant officially dried up a few weeks ago. San Juan County had issued $3.2 in tax-free industrial revenue bonds to fund Desert after a request from Sithe Global in 2007. But the fine-print required that Desert Rock have an EPA permit in order for the bonds to be valid. After last fall’s revocation of the permit and a deadline in late June, the bonds have expired. Nonetheless, Sithe Global remains optimistic. Keeping his comments to the point, Dirk Straussfeld, Sithe’s executive vice-president, said, “We are reviewing the options for this project to take into account the energy market and the changed permitting environment.”Conservationists, on the other hand, charge that Desert Rock has officially run out of options. “There aren’t any upsides for Desert Rock anymore,” said Mike Eisenfeld, of San Juan Citizens Alliance. “There aren’t customers for Desert Rock power. There’s no transmission in place. And now there’s no funding. The bottom line is no permits, no project.” In addition, Desert Rock’s political foundation is on the verge of evaporating. The plant has always been proposed in conjunction with the Navajo Nation and has long been a pet project of Navajo President Joe Shirley, Jr. However, Shirley’s term is nearly up, and both of the frontrunners for the presidency are decidedly anti-Desert Rock. Candidate Ben Shelly, who is Shirley’s vice-president, is adamantly opposed to Desert Rock and has plainly said that the plant is “not going to happen.” Linda Lovejoy, Shelly’s rival and a New Mexico state senator, recently indicated her aversion to the plant in her choice of a running mate. Lovejoy will be joined on the ticket by Earl Tulley, a Navajo conservationist who served on the board for one of Desert Rock’s chief rivals – Diné CARE, a Navajo environmental organization. “Desert Rock is dead,” said Lori Goodman, treasurer for Diné CARE, “and everyone on the Navajo Nation believes the power plant is dead, except for Joe Shirley. People are aware of the health impacts of coal-fired power, and it’s time for a new era in the Four Corners.” In this spirit, Goodman joined dozens of other Navajo activists and politicians at a conference in the Navajo capital, Window Rock, Ariz., last weekend. The goal of the gathering was to spotlight and advocate large solar and wind projects on the Navajo Nation. “We’re looking at ways to mobilize the people, begin work on renewable projects and do it in a timely manner,” Goodman said. The Four Corners’ abundant solar and wind resources and vast expanses of untapped acreage make the region an ideal candidate for large renewable energy projects, according to Eisenfeld. These assets coupled with strong momentum away from coal-fired power can only lead in one direction. “It’s time for the electric and power industries to start realizing and reflecting the real costs of coal-fired power,” Eisenfeld said. “We hope our region can be on the forefront of developing renewable energy projects that can have both economic and environmental benefits.” The Navajo Nation is already charged up for this new direction, according to Goodman, who added that Desert Rock has already been forgotten. “This is a good time on the Navajo Nation, and we’re all excited about the future,” she said. “Desert Rock is dead.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel

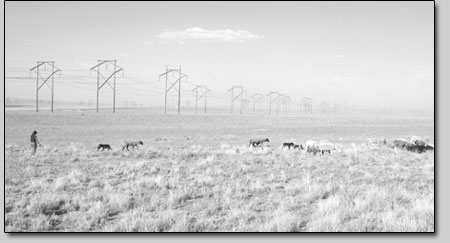

The air is rapidly clearing over the Four Corners region. The proposed Desert Rock Power Plant suffered another potentially fatal blow when its industrial revenue bonds – the mechanism for funding the plant – expired recently. While the controversial coal-fired plant’s backers are putting on brave faces, opponents are already celebrating Desert Rock’s demise.

The air is rapidly clearing over the Four Corners region. The proposed Desert Rock Power Plant suffered another potentially fatal blow when its industrial revenue bonds – the mechanism for funding the plant – expired recently. While the controversial coal-fired plant’s backers are putting on brave faces, opponents are already celebrating Desert Rock’s demise.