|

| ||||

| Diving bells, butterflies and grocer's sons SideStory: Just the Facts

by Willie Krischke When I consider how my light is spent, Ere half my days in this dark world and wide, And that one talent which is death to hide Lodged with me useless, though my soul more bent To serve therewith my Maker, and present My true account, lest He returning chide; “Doth God exact day-labor, light denied?” Those are John Milton’s words, written soon after he lost his sight. Later, he would write Paradise Lost, one of the greatest works of literature ever written. Squint a little, and they also could be the words of Jean-Dominique Baubie, who at the age of 44 had a massive stroke. He awoke from a coma only able to blink, and managed to write his autobiography via blinks before he died two years later from pneumonia. Baubie might get shifty hearing Milton’s lines about serving his Maker, but his desire to present a true account is the same. “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly,” directed by Julian Schnabel, is the movie made from that account. Baubie has what is called, medically, “locked-in syndrome;” Schnabel clearly sees “locked in” as the human syndrome. To live locked in is an act of defiance; living may be miserable but dying is letting the other guy win. Whether that other guy is God, the devil, or your own body perhaps depends more on your perspective than your circumstances. Almost the entire first half of the movie is filmed directly from Baubie’s perspective, including his blurry sight, lack of peripheral vision, and every single person’s annoying knack of getting right up in his face to talk to him. It’s amazing how well this works on screen. For a few moments I was lost musing about how watching a movie is like being paralyzed with only one eye open. You see what you are shown. You can’t look away or change the view, even if you’re pretty sure the real action is going on somewhere else. Jean-Dominique (played by Mathieu Amalric) learns to communicate primarily through the incredible patience of a therapist and his wife. They recite the alphabet for him and he blinks when they say the letter he wants. It’s a little disconcerting to watch this process in the subtitles. Naturally, the letters he chooses don’t add up to the word that appears on the screen. More disconcerting are the things he chooses to say. It turns out Jean-Do has a poet’s soul, and his prose is lyrical, image-rich and startlingly fresh. I guess when it takes half an hour to write a line, you choose your words pretty carefully. Milton knew about that.

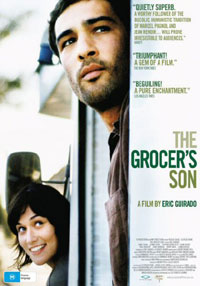

“The Diving Bell and the Butterfly” might sound either crushingly boring (a protagonist who can do no more than blink? Really?) or like Hallmark material (O, the triumph of the human spirit!) It’s neither. Though he looks a bit like him, Jean-Do is no Christopher Reeve. There is ample reason to think he’s a real ass, both before and after the stroke. But there is also ample evidence that he took care of his father, loved his kids, and was pretty confused about things like “happiness” or “fulfillment.” Like him or hate him, you can’t help but admire his defiant determination to do the impossible under impossible conditions. I can’t say that I found his story inspiring, but I certainly marveled at the incredible stubbornness of the human spirit, and at the courage of Jean-Dominique Baubie in his attempt to tell a true account. “The Grocer’s Son” Now here’s a Hallmark movie for you. Nicolas Cazale plays a prodigal son who has run away to the big city, vowing never to return to his parents’ home in the beautiful French countryside. But then his father has a heart attack on the same day Cazale loses his crummy job as a waiter. The stars have never lined up so perfectly for a homecoming. Cazale takes his pretty next door neighbor (Clotilde Hesme) along, clearly hoping that there’ll be only one bed and they’ll have to share it. She has other plans and just needs a quiet place to study so she can pass her entrance exam for a university in Spain. Cazale drives his father’s grocery truck, which operates kind of like an ice cream truck without the music. His customers are mostly over 70 and are quite used to paying for their groceries with eggs, jam or endless credit. “We’ll pay you next week…or next month,” one old man says. “Or next year,” his wife chimes in. Cazale has little patience for them, and it’s awfully good that Hesme comes along every now and then, or Cazale would end up ruining his father’s business while he’s still in the hospital. You can pretty much guess where this is going, and director Eric Guirado does nothing to make you think otherwise. Cazale learns to care about his customers, especially a senile man who raises chickens, and the ending is warm and happy if not exactly satisfying. Cazale’s problems simply go away without really being solved. But “The Grocer’s Son” makes up for what it lacks in content or originality with oodles of charm and wry humor. This movie won’t change your life, but it might be just right for date night. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel