|

| ||

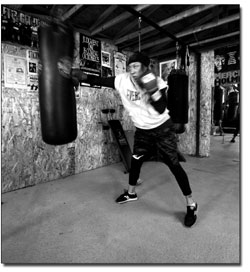

| Durango’s knockout artist

by Stew Mosberg Amie Iawaski launched off the stool and raced across the ring, hoping to catch her opponent off guard, but she hadn’t counted on the lightening quick reflexes of her opponent. Thaddine Swift Eagle Johnson feinted left, moved right, ducked Iawaski’s jab and slammed a fist into the antagonist’s solar plexus, driving her to the canvas and winning the Women’s Professional Boxing Association’s Intercontinental Featherweight (126 pounds) Championship. Elapsed ring time: 55 seconds. For Thaddine, of Durango, it was a long fight. Her previous victory, a few months ago, came in just 13 seconds into the first round, also courtesy of a body shot. For a woman who spends more time dressing for the bout than in the ring, traveling around the country for matches seems to be the more grueling part of her off-beat career. But another difficult part of being a woman prizefighter is even getting bouts. Women’s boxing, both professional and amateur, is in its infancy compared to its male-dominated counterpart. Most trainers and managers want nothing to do with women fighters. “They think of us,” says Johnson, “as meat, or a date.” In fact, it is so difficult to acquire a manager or find a suitable trainer that Johnson does both by herself. Getting on the “card,” or program, is tough enough when one considers how few opportunities there are, but in Thaddine’s case, it is more complicated because many fighters don’t want to risk getting in the ring with her. Women’s fisticuffs is more accepted in Europe, and according to Johnson, a fight can net a female pugilist as much as $20,000 a bout. In the United States, if you can get into the arena at all, a fight of four, two-minute rounds might earn you a couple thousand bucks, at most. So why risk injury, humiliation or worse? Johnson points out that, while for her, it is not “of life and death importance,” she set a goal for herself to win the world title. That, however will take getting more fights, being seen, winning, and gaining higher rankings within the several sanctioning bodies that control who fights who. While women are still considered a novelty act, a few more promoters are booking female preliminary fights, created to precede the night’s main event. And New York State recently appointed a woman, Malvena Latham, as the Boxing Commissioner, although it remains to be seen what impact that will have on women warriors.Another promising factor, sure to increase awareness and exposure for female boxers, is the announcement that the Olympic committee might consider women’s boxing in the 2012 London Games. Of course, it won’t affect Thaddine’s career because as a professional she wouldn’t be eligible to try out for the team in the first place. Nonetheless, she has a fight scheduled in Hawaii on April 11 and will be featured in the main event in Kansas on June 5. Both fights are great opportunities for the knockout artist to be seen and to improve her rating. But unlike Laila Ali, the boxing champion daughter of Muhammad Ali, there’s only a small chance Thaddine’s fights will ever be seen on television. But there is also a possibility Johnson will be fighting in Las Vegas again in June. Vegas would be a homecoming of sorts, because Thaddine used to train there at Top Rank, owned by Bob Arum, one of the sport’s leading promoters. She concedes however, the bout might not happen because she would have to pay for her own medical, “I might have to turn that one down unless the promoter pays for it,” she says with a hint of disappointment. Thaddine is perhaps more familiar to Four Corners residents as an award-winning painter and photographer. She is also a former dancer with Alvin Ailey, a caregiver to her wheelchair-bound mother, and a mentor to troubled teens. Amidst all that activity, she still finds time to train several days a week in Farmington and Ignacio, banging away at light and heavy bags, shadow boxing, and slamming hand pads with such power it smacks the guy holding them into the wall. Her roster of accolades includes being a three-time world kickboxing champion and – her most coveted and proudest achievement – winning the Golden Gloves in 2000. She won that amateur stepping stone tournament, without prior boxing experience, while her now deceased father was in the audience. That memory still makes her wistfully happy and proud. Although many people would like to see boxing abolished entirely, and as primordial a sport as it is, there’s no denying the conviction, the grit and the sheer guts it takes to get in the ring with another human being and overcome your fear and remain focused. Growing up on the streets of Queens, traveling to matches in places as far flung as South Philadelphia, Las Vegas, Minnesota, Virginia and even North Dakota, or working out in everywhere from tiny boxing clubs to the world-famous, sweat-soaked, Gleason’s Gym in New York, Thaddine Swift Eagle Johnson has remained a powerhouse. Her strength and speed in the ring is matched only by her fierce determination outside of it. Sitting, swathed in her electric-blue “Everlast” top, sipping a chai tea at a java joint in Durango, she exudes a calm, confident, persona; a warrior who can and will let nothing stand in her way of achieving whatever goal she sets for herself. She already has. • Stew Mosberg is a freelance writer and boxing enthusiast. His father was a Golden Gloves lightweight champion, an uncle was a boxing gold medalist in the Olympics, and his brother was an Eastern Collegiate Flyweight Champion. Stew, however, prefers pounding the keyboard to being pounded by an opponent.

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel