|

| ||||

| A fragile search for ‘Truth’

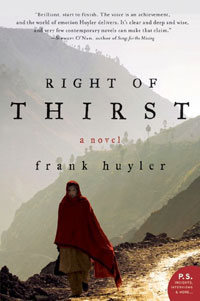

by Joe Foster Right of Thirst by Frank Huyler. Harper Perennial, 2009. 384 pages. Someone recently asked me why all my book reviews here in the Telegraph are “glowing,” why no bad reviews of books I hated? This is a fair question. I’ve heard it said that a reviewer shouldn’t be trusted until you see what they don’t like. I happen to disagree with this. I just want people to read good books, great books, and don’t really want to read bad books myself. What it comes down to is this: if you read something I’ve written about a book, it’s been through one heck of a filtering process. I choose good books for a living and am constantly searching for that next great read, that next book that maybe, just maybe, will change me for the better, make me see the world a little more clearly. (If you want to hear about books I hate, just buy me a beer and I’ll rant for hours.) I yearn to be awed and need to be challenged, and sometimes a book just snaps into place in my psyche. Honestly, nonfiction rarely does this for me. A great novel contains more Truth, capital “T” Truth, than an entire library of reference books. Those are facts, but Truth, that great unknown, unreachable Truth of our human existence, must be found in our

I think Frank Huyler’s Right of Thirst plunges us right into the middle of this mass. The amorality of circumstance, wearying self-doubt, suspicions of limitations reached, each character is plagued, and Right of Thirst simply puts their discomfort on display for our examination. Charles Anderson, after losing his wife, becomes unmoored, lost within himself. He is talked into going to the Middle East to work in a refugee camp. There has been an earthquake, and his skills as a doctor might be of use. Things, when he gets there, are not so simple, and the rest of the story is unexpected. The patience-breaking wait for the refugees to appear, the politics and violent conflict of the region, the poverty of the mountain clans, and the arrogance of the military complex serve as a backdrop for a few people, strangers from around the world, to slowly get to know one another. This dynamic is where the real depth of this novel is revealed. There are no good guys, no bad guys, no card board cutouts serving as characters, but real people, with their petty motivations and altruistic ideals, people realizing their own prejudices and their own shortcomings. The distance between the poor and the wealthy is immense and seemingly insurmountable, but perhaps easier to bridge than the distance between cultures. The reader gets to know these characters at the same pace that Charles Anderson gets to know them, which serves to reveal, possibly, our own prejudices and ill conceived expectations. As for expectations, have none when you crack this one open. The story will take you to places unexpected, uncomfortable and beautifully tender. There is one word I would use to describe this book: tender. Huyler reveals these characters so gently and with so much love that we realize that this Truth we seek is fragile and must be revealed slowly and oh so gently or it will simply vanish. I’m not sure if I’ve ever read a novel that holds its characters in such high regard. While displaying their weaknesses, we see hints of their strength. Watching them struggle through such muddled and trying circumstances, we see their humanity, and within theirs, a glimpse of our own. I believe that (and the hokey-pokey) is what it’s all about. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel