|

| ||||

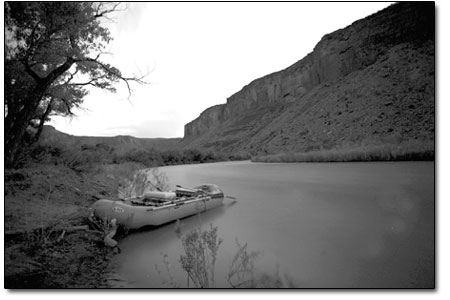

| ‘A complicated river’ SideStory: A celebration of the Dolores: Dolores River Fest set for Saturday

by Missy Votel If ever there was an enigma wrapped in a riddle, it would be the Dolores River. Not only does the “River of Sorrows” take an abrupt northward about-face on its 250-mile journey to the Colorado River, but the origins of the name itself (“El Rio de Nuestra Senora de las Dolores,” possibly bestowed by a Spanish explorer in the mid 1700s) are shrouded in mystery. However, more than 250 years after the first white settlers laid eyes on it, the Dolores continues to confound those looking to protect the increasingly precious resource. “It’s a complicated river,” said Amber Kelley, a Cortez native who now lives in Dolores and works as the Dolores River Campaign Coordinator for the San Juan Citizens Alliance. In her role, Kelley helps head up the Dolores River Coalition, a group conservation and recreation organizations that “care about the fate of the Dolores River.” The coalition, in turn, gives input to the Dolores River Dialogue, a broader group made up of stakeholders from farmers to federal agencies. That group formed in 2004 with the goal of balancing ecological conditions of the stretch of river below McPhee Reservoir with water rights, and recreational interests. To make things more complex, that Dolores River Dialogue, or DRD, dovetailed in 2008 to help form the Lower Dolores Management Plan Working Group. Also made up of a broad cross section of interests, the work group is preparing recommendations for an update to the San Juan Public Lands Center’s 1990 Dolores River Management Plan, slated for later this fall. Throw in the Bureau of Reclamation and Dolores Water Conservancy, which oversee operation of McPhee Dam, the Bureau of Land Management, which is responsible for management of much of the river’s surrounding public lands, as well as a Wilderness Study Area, Wild and Scenic River suitability and increasing pressures from the mining and oil and gas industry, and the scenario has more twists and turns than the meandering river itself. Nevertheless, there is an overriding theme to it all: protection of the Dolores and its myriad uses. It is this common thread that has been guiding the work group’s attempt to reconcile the different uses with preserving the river, or in some cases, bringing it back to life. Depending on who you talk to, the general consensus is that since the mid-1880s, roughly around the time the Montezuma Valley Irrigation Co. dug its first tunnel to bring water to area farmers, the Dolores River has been reduced to a trickle come mid-July. (What happened prior to that is up for discussion, although historical hydrograph data suggests more sustainable flows.) In order to offer communities dependable year-round water, the Dolores River project was approved in 1968. McPhee Dam was completed 18 years later, ensuring irrigation for 61,000 acres of land and 8,700 acre-feet of water for municipal and industrial use. While the Dolores Project succeeded in supplying water to agriculture, stretches of the Lower Dolores still ran low, or even dry, in subsequent summers. However, it wasn’t until the formation of the DRD that issues such as health of the downstream fishery and riparian corridor, not to mention sustainable recreation flows, were brought to the forefront. Now the work group, which has been meeting monthly since December, is taking that effort one step further. “The biggest thing the work group is doing is looking at each reach of the river and asking what are the opportunities to advance the health of the river and the best tools to achieve that,” said Mike Preston, manager of the Dolores Water Conservancy and a work group member. The work group has divided the river into eight distinct sections, but the bulk of concern is over the first five, from the dam to the confluence with the San Miguel River. Preston said the four major areas of concern include: the health of the cold-water fishery, including non-native trout; the warm-water fishery, which includes native species such as suckers, chubs and minnows; the riparian zone, which includes eradication of tamarisk and re-establishment of native cottonwoods and willows; as well as the geomorphology, including sediment build up and flow. “The opportunities to do something positive for the river vary from reach to reach,” said Preston. “The original flow from McPhee was designed with the sport fishery in mind, but the objective now has grown much broader.” According to fellow work group member Ann Oliver, the South San Juan Mountains Project Director for the Nature Conservancy, the Dolores ecosystem is unique for several reasons. “It supports a number of natural values,” she said. “It has unique riparian plant and native warm-water fish communities.” According to the Division of Wildlife, the flannel-mouth and blue-headed suckers are native to the Lower Dolores. This particular population is rare in that it has have not hybridized with the white-headed sucker as in other parts of the Colorado River drainage. “They are not listed as endangered, but there is concern about them,” she said. “They are one of the driving values of the work group.” In addition to the native fish, the Lower Dolores is also home to the eastwood monkeyflower and the kachina daisy, both found in only a few dozen sites throughout the Four Corners. Aside from the stresses low flows put on the downstream ecology, Oliver sees the biggest threats to the Lower Dolores as invasive species, such as tamarisk and Russian knapweed, and the extractive industry. In addition to past and possible future uranium mining in the area, natural gas drilling could also have impacts. Recently, the Denver-based Bill Barrett Corp. began conducting natural gas exploration in Paradox Valley using Dolores River Project water in the hydraulic frac-ing process. It is this sort of development that Kelley, of San Juan Citizens Alliance, is paying special attention to. While there are no oil and gas leases within the riparian zone, it is allowed atop the surrounding rims. “If the properties are developed above the rim, they will definitely have effects on the riparian zone. We are really watching that and hoping it’s done responsibly.” And while some members of the work group see industry as a threat, others see too much federal oversight as another stumbling block. Although the Dolores was deemed by the U.S. Forest Service to have the “oustandingly remarkable values” suitable for Wild and Scenic River status, Preston, with the conservancy district, would rather not see that happen. In addition to creating another level of bureaucracy that would impede the consensus-building of the work group, he said there are also worries over water rights. “Many people are concerned about Wild and Scenic because of federally restricted water rights,” he said. Rather, he would like to see other preservation alternatives explored, noting that his top priority is making sure water rights are met. “We have to account for every drop of water that comes out of the dam,” he said. “We also try to cooperate any way we can from an ecological standpoint. But we need flexibility to work collaboratively and make adaptations without a lot of formal restraints.” Oliver and Kelley note that they are not tied to Wild and Scenic, but rather it is just one option available. “It’s definitely a contentious issue because of water rights,” Oliver said. “Our purpose is to understand it as a tool and understand what other tools are out there.” However, all noted that nothing will work without the buy in of all parties. “There is a lot of interest and a lot of people committed to this, so it’s worth taking the time to come up with something everyone can live with,” said Preston. • The Lower Dolores River Work Group plans to submit recommendations to the BLM sometime this fall, after which time the official management plan and public scoping process will take place.

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel