|

| ||||

| Weighing in SideStory: National Eating Disorders Awareness Week

by Jules Masterjohn

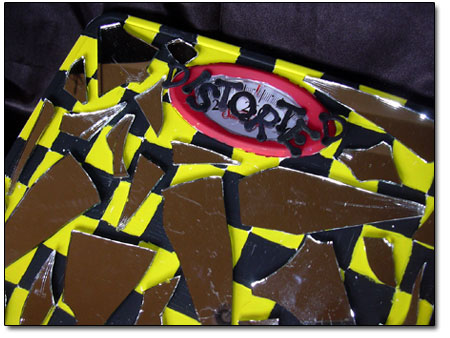

The idea to use the scale as a format for the art exhibit came by way of Joanie Trussel, a local therapist and leader in the field of eating disorder treatment. Through her work over the last eight years, Trussel has come to understand that the bathroom scale is frequently used to determine how girls and women feel about themselves. “I had seen the idea on a NEDAW website,” she told, “and liked that the scale could be changed from being the judge and jury about ourselves to something more positive, that the art could change our thinking about it a bit.” Mandy Mikulencak, one of the local organizers for NEDAW, did just that with her artwork, “Theory of Relativity,” which mixes science and imagination. On a typical bathroom scale painted sky blue, she mounted a large Styrofoam yellow-orange sun and attached small, vibrantly colored balls to it, each representing a planet in the solar system. Mikulencak makes her message clear with the words: “Numbers are Irrelevant: Ditch the Scale,” followed by a list of what a 150-pound person on Earth would weigh on other planets: Mercury, 56 lbs; Pluto, 10 lbs; and the Sun, 4,060 lbs. Hers is a light-hearted rendition of a measuring tool that can become, in the minds of those suffering from an eating or exercise disorder, a damming summation of one’s self-worth. Another poignant depiction of suffering, Kim Riddle’s “Distorted,” a checkerboard surface in caution yellow and black underlies pieces of shattered mirrors, reiterating the idea of the scale as a skewed reflection of oneself. Riddle’s scale reflects a distorted self image, allowing the viewer to see only fragments of herself. Trussel has observed, “The thread that I see running through this issue, more than anything, is low self esteem. Feeling powerless and not feeling good about yourself are the most constant factors – not body image. That’s what the illness turns into, but it doesn’t begin there.”

According to Trussel, obesity is attributable to eating disorders and is part of the illness’ continuum. “Food is very symbolic. Eating is one of the ways we can nurture and comfort ourselves when we are in pain.” In a disordered mental state, “When we eat, we are taking in food in the hope that we will be loved; then we can get rid of (the food) because we don’t feel loved.” The University of Maryland Medical Center website states that there are complex factors at work in the development of anorexia, exercise anorexia,and bulimia, from family issues and personality disorders to possible genetic factors. Ninety percent of those suffering from anorexia are female, though since 2000, the number of boys and young men reported with the illness has increased. Recovery rates vary between 23 and 50 percent, with recovery taking four to seven years. Up to 25 percent of those suffering from anorexia will die. Cultural factors, too, play a significant role with the media promoting unhealthy body images, especially for girls and women. Trussel pointed out, “Marilyn Monroe was a size 14. Today we have a size 0.” Recognizing the power that popular culture has on forming young people’s ideas about themselves, the European fashion industry has recently required that models must meet a minimum BMI (Body Mass Index) in order to walk the runway. This accountability has helped to raise awareness about the illness. A vicious cycle of shame surrounds those who suffer with eating and exercise disorders. For most, the hardest part of the illness is admitting that there is a problem and one is in need of help. “I needed someone to guide me to recovery to find help, I was too ashamed to find it for myself,” a woman in recovery admitted. It was a close friend of the woman’s who finally expressed concern, “She told me that she was worried I was headed to a dangerous place.” Artist and educator Margaret Pacheco hopes that, “Look for the Hearts,” her white scale covered in black line drawings of trees and hearts, will reach out to viewers and invite them to stand on it. For Pacheco, who does not have personal experience with the disorders but knows many women who do, compassion is the antidote to the emotional pain that is held within. “When anyone steps on the scale, I hope they will take the statement, ‘Blessings and Peace to Anyone Who Steps Here,’ to heart and feel that whatever their weight, they are just right, and can feel blessed and peaceful.” Like Pacheco, who has made her scale to show support for those suffering, one anonymous woman’s mother, three sisters, and three aunts are all making scales in support of her and others with eating disorders. “It’s a lovely way to say, ‘We are in this with you,’” Mikulencak offered. The scales will be on display at the Durango Public Library from Feb. 22-28. For more information about NEDAW, contact Mandy Mikulencak at 375-1303. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel

A common household object, the bathroom scale, is being used as a potent symbol for self image in the upcoming National Eating Disorder Awareness Week (NEDAW) art show. The local NEDAW committee put out a call for individuals to “artify” bathroom scales with the goal of bringing public awareness to eating and exercise disorders. Organizers expect about 20 scales to be on display at the Durango Public Library next week.

A common household object, the bathroom scale, is being used as a potent symbol for self image in the upcoming National Eating Disorder Awareness Week (NEDAW) art show. The local NEDAW committee put out a call for individuals to “artify” bathroom scales with the goal of bringing public awareness to eating and exercise disorders. Organizers expect about 20 scales to be on display at the Durango Public Library next week.