|

| ||||

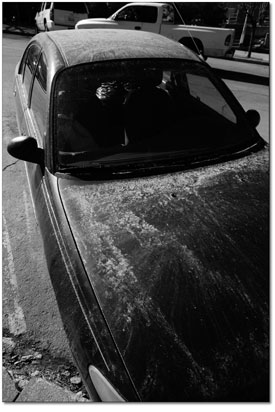

| Dust on the horizon

by Will Sands Another winter is literally biting the dust in Southwest Colorado. Regional forecasters, scientists and residents are marking a spring plagued by a record number of dust storms. Although the skies are currently clear, dust storms have done their part to accelerate run-off and denude the region’s snowpack. Chris Landry, of the Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies, has been getting his fingers dusty since 2002. At that time, he set up shop in Silverton with a vision for a research station that could assist scientists. To that end, he got permission from the U.S. Forest Service to establish what amounts to an outdoor laboratory. Throughout the winter, he takes measurements at two sites in the San Juans relatively unaffected by localized sources. One of his first major clients and collaborators was Tom Painter, now of the University of Utah, who wanted to test the proposition that dust blown in by storms affects the rate of runoff. Thanks in part to Landry’s observations, Painter is concluding that the dust has a significant impact, noting that the dirt in the snow absorbs heat and melts the snow. Pure snow reflects the sun’s rays and withstands warmth to a much greater extent. The impact of dust has been especially significant this winter. As of press time, 13 separate dust storms had ripped through the San Juan Mountains, marking a high point since Landry and company started their observations seven years ago. “It is important to note that dust storms have been affecting the region for a very long time,” Landry said. “But in terms of our short and limited record, this winter and spring have had the largest number of events.” Hesitant to point fingers, Landry noted that the workings of Mother Nature are one explanation for the phenomenon. The winter of 2008-09 was an especially windy one, and intense storm cells picked up dust over the Utah and Arizona deserts and then deposited it in the Colorado Rockies. “The obvious explanation is that there have been more strong and windy systems tracking through the Colorado Plateau and into the Rockies this year than in past years,” Landry explained. One man with several additional explanations is Jason Neff, a biogeochemist with the University of Colorado-Boulder. Neff’s quest for dust has brought him to the San Juans in recent years, where he has studied core sediments from several high-altitude lakes. The samples have enabled Neff to look thousands of years back in time. After analyzing the results, the team has arrived at a conclusion – dust storms are directly tied to human activity. Over Neff’s 5,000 year timeline, the first spike in dust was in the late 1800s, during the first significant settlement of the Southwest. “Prior to settlement, there was not a lot of grazing, roads or soil disturbance,” Neff said. “The soil surfaces were stable, covered with biologic crusts and armored against erosion.”

Another spike has hit in recent years, and the size and frequency of dust storms appear to be on the rise again. “In the late 1800s, dust loading skyrocketed and was about five times as high as our background data,” Neff said. “Today, dust is about three or four times the background, and livestock, off-road vehicles, human development, dirt roads and weather are all factors.” Though causes may be up for debate, the effects are not. Heavy dust loading in the San Juans contributed to last week’s spike in run-off on the Animas River. After just a few warm days, flows shot up to nearly 2,000 cfs before subsiding with the cooling temperatures. The region’s snowpack – the water supply for coming summer months – dwindled dramatically during the same period, falling from 98 percent of average on April 18 to 73 percent of average early this week. To make matters worse, the Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies has observed similar dust loading all over the Colorado Rockies, which will mean a widespread affect on the timing of run-off and the volume of water supplies in coming weeks and months. Recognizing the stakes, eight major water agencies in Colorado have entered into contracts with the Center to predict when the meltdown will begin. “We’re involved and helping fund the study because when you get dust events it does affect the timing of run-off,” said Bruce Whitehead, executive director of the Southwest Water Conservation District in Durango. “The dust definitely impacts the long-term flow and can be serious detriment to senior water rights holders.” On the Animas River, early run-off promises to have negative impacts on agriculture, according to Whitehead. In addition, the wind and dust increase the rate of sublimation, where moisture simply evaporates into thin air, leaving the basin thirsty after all but the biggest winters. These factors will also become more complicated as the region grows. “As the basin’s water becomes more appropriated, there’s more demand on the supply,” Whitehead said. “Though the Animas is not considered overappropriated at the moment, this may change in the future, and the administration of the river will have to change with it.” Whether fields, crops or livestock go thirsty later this summer remains an unknown. But for the time being, water and river users should expect another big bump in Animas River flows in coming days and weeks. “We just saw the first significant surge in snowmelt of the season,” Landry said. “That was curtailed a bit by a very thin layer of fresh snow over the weekend. But that clean new snow isn’t going to last more than a day or two, and when warm temperatures hit, the melt is sure to start again.” Neff added that dust storms are certain to be popping up on the local radar for many years to come. “I suspect people haven’t really considered dust as a threat before this,” he said. “But it’s a pretty big deal and an impact on air quality and water supply. I’m sure this year has changed a lot of minds.” In closing, Whitehead spoke for the entire basin and said, “The (storms) are no good for the snowpack, the air quality or our quality of life. I just hope we’re done with dust storms for the year.”

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel