|

| ||||

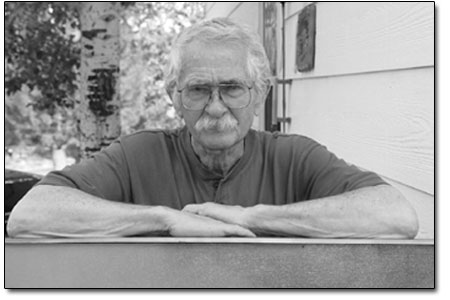

| An ode to Stanton SideStory: Paying homage

by Jules Masterjohn

One can’t help but smile, thinking that the self-described “worker of the cosmos” took the opportunity to hitch a ride on a celestial rock to a planet in some far-off galaxy. When I think of Stanton and heavenly bodies, many paintings depicting cosmic events come to mind. In his large-scale landscape “Look Out Point, Mesa Verde National Park,” a herd of cows grazes in the foreground pasture as a pair of moons – one red and one turquoise – hovers in a cobalt blue and violet dusking sky. The silhouette of Mesa Verde is the fulcrum of the horizon. Another painting from the same series of 18 that Englehart donated to Fort Lewis College Community Concert Hall and now on permanent display there is “North Park, Walden, Colorado.” I recently visited this painting and noticed, once again, that the sun’s intensity, though dulled by dark red clouds, can be seen in the turquoise blue meandering sliver of a river that bisects the sensually shaped verdant valley. “North Park” functions on many levels, from a straight-ahead landscape with a realistic color palette to a depiction of the eons-old courtship between the Earth and her consort, the sky. There is primal love being made on this canvas, and my being is shaken each time I see it. I want to crawl into it and lay my body down at the valley’s edge and nestle against those brushstroke mountains, at the same time being totally vulnerable under the open sky.

My response to this painting is not the isolated invention of my own imagination. Rather, it is a direct response to the embodiment in Stanton’s paintings of “the collective human experience” that he intended in his work. He said, “The land is so vital and dynamic and holds within it the story of how biologically creative life is. That’s what my paintings reflect.” Not all of his paintings are gentle and generative in theme. His outrage for the despoiling of his beloved Earth can be sensed in the Women Series. In these mixed-media paintings, female figures are compressed into confined spaces, surrounded by guillotine-like forms, laser beam lines and smoke clouds. Stanton explained, “I used the bound women to symbolically express my concern for the damage to nature caused by misguided technology.” These disquieting images speak powerfully and poignantly about a world that he felt had gone terribly awry. Stanton Englehart was not only a lover of the canvas, he was a lover of all of life. He expressed his passion for being alive in everything that he engaged in – from painting and fly-fishing to cycling and teaching. Anyone will tell you that Stanton was generous in his actions and gentle in his speech. He loved to tell stories, and he told them well. Stanton possessed that rare ability to digress in the most interesting ways and come full circle to his original premise, with the listener feeling like a journey of epic proportions was undertaken. Joel Jones, former Fort Lewis College president, Stanton’s colleague and long-time friend, wrote in the book, Stanton Englehart: A Life on Canvas, “For Stanton, each conversation with a student, a colleague, a collector, or a friend is an exploratory venture into the landscape of the mind, a walk he has always taken with passion, empathy, style, and grace.” Clearly, Stanton valued his relationships above all, and those in his company knew he was fully present with them. The most consistent presence in his life was his wife and life-partner, Pat, to whom he was married for 60 years. In the dedication for A Life on Canvas, he wrote, “To my wife, Pat, you are the stretchers and glue of my life on canvas. I thank you for being the fabric of our family, the light beneath my colors, and the inspiration for my continuous line of sight.” Stanton was never timid about expressing his feelings towards her and often acknowledged Pat’s contributions to his life and art. He offered, “Our marriage has become a means to support individual growth. It functions on a dynamic balance of shared experience and individual freedom, and is, for me, the essence of creativity.” Stanton Earl Englehart once mused that his initials, SEE, might have predisposed him to a life as an artist. Prophetic was this naming, for during his 50-year career, he produced more than 5,000 paintings and over his 30 years as an art professor, he influenced many hundreds of students. During his 78 years of living, he touched many lives, always revealing the landscape of his heart. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel

It was 3:20 a.m. on Wed., April 22. In the wee hours of Earth Day, at the height of the Lyrid meteor showers, and while Venus temporarily slipped behind the crescent moon with Mars nearby, artist Stanton Englehart passed from this world.

It was 3:20 a.m. on Wed., April 22. In the wee hours of Earth Day, at the height of the Lyrid meteor showers, and while Venus temporarily slipped behind the crescent moon with Mars nearby, artist Stanton Englehart passed from this world.