|

| ||

| Busting the boom

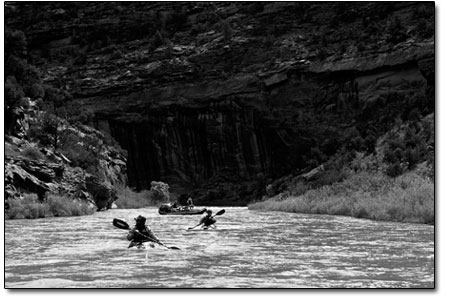

by Will Sands The Colorado pikeminnow, razorback sucker and humpback and bonytail chubs could be unraveling Western Colorado’s second uranium boom. Last week, four conservation groups took on the federal government for opening the floodgates to uranium mining without assessing the impacts on the Dolores and San Miguel rivers. Western Colorado’s first uranium boom arrived in the 1950s with the beginning of the Cold War. At that time, prospectors with newly patented mining claims and Geiger counters in hand descended en masse on the canyon country west of Durango. Many walked away with fortunes but left a legacy of mine waste and radioactive tailings in their wake. Three years ago, uranium prices once again spiked, and prospectors and mining companies started eyeing the desert of the Dolores River drainage. Local uranium mining got a big nudge in the summer of 2007 when the Department of Energy announced its Uranium Leasing Program. At that time, the agency opened 27,000 additional acres in San Miguel, Montrose and Mesa counties to prospectors seeking the radioactive ore. With this acreage, the DOE estimated that regional mines would produce 2 million tons of unrefined uranium per year. At the time of the announcement, Tracy Plessinger, DOE project manager, noted, “There will be some impacts,” she said. “Anytime you’ve got an extractive process, there will be impacts. But those impacts won’t be on the entire 27,000 acres. We estimate that there will be a total of 750 acres spread throughout the entire 27,000 that will be disturbed.” Plessinger also downplayed the impacts on human health and safety, saying the agency carefully examined the threat of radioactive exposure to mine workers and the public. “All of the risk levels came back very, very low,” she said. “The highest risk for radiation exposure was for those residing nearby and that was only eight people in 100,000. Is there an impact? Yes. Is it significant? No, not in the realm of human health risk.” Based on these facts and that many of the lease tracts in question had already been mined, the DOE issued a “Finding of No Significant Impact” and authorized the Uranium Leasing Project to begin immediately. However, the impacts of nearly three years of mining could be much more significant than Plessinger imagined. On Friday, a team of conservation groups – the Center for Biological Diversity, Colorado Environmental Coalition, Information Network for Responsible Mining, and Center for Native Ecosystems – announced their intention to fight the leasing program in court. The groups uncovered new documents that suggest that the Department of Energy deliberately failed to consider the impacts of water depletion and contamination to threatened and endangered species – including Colorado pikeminnow, razorback sucker, and humpback and bonytail chubs. The groups go on to allege that the agency ignored warnings from the Bureau of Land Management, and the notice gives the DOE and BLM 60 days to remedy the violations of the Endangered Species Act. “Risking species, public lands and scarce Western water with irretrievable uranium contamination is profoundly short-sighted,” said Taylor McKinnon, of the Center for Biological Diversity. “But that’s exactly what the Department of Energy has done. The department’s choice now is to comply with the Endangered Species Act or be sued for these new violations.” The groups noted that uranium mining and milling resulting from the lease program will deplete Colorado River basin water and may pollute streams and rivers with toxic and radioactive waste products. Contamination from abandoned uranium mining operations in the region has been already been implicated in the decline of native fish species. Consequently, the groups have demanded that the agency initiate a formal consultation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or face litigation. “Even small amounts of some of these pollutants, like selenium, can poison fish, accumulate in the food chain and cause deformities and reproductive problems for endangered fish, ducks, river otters and eagles,” said biologist Megan Mueller of the Center for Native Ecosystems. “It is irresponsible for the Department of Energy to put fish and wildlife at risk by rushing to approve numerous uranium mines without adequate protections to prevent pollution.” In addition, the lease area spans some of Colorado’s most pristine wilds. The Dolores River watershed is renowned for its untrammeled deserts and rivers and supports many unique ecosystems. “We hope the DOE will do what’s right in protecting the land, water and people from a massive and flawed development plan rushed through by the Bush administration,” said Joe Neuhof, West Slope director for the Colorado Environmental Coalition. “This land has plenty of long-term value for its recreational opportunities and wildlife so there is no reason to rush ahead without properly assessing potential impacts.” Whether the department will “do what’s right” or face down the conservationists in court should become apparent in coming weeks. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel