|

| ||

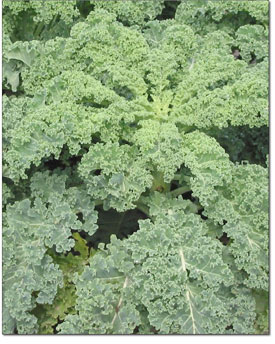

| Winter salads

by Ari LeVaux One afternoon last November, long after the frosts of autumn had begun their nightly visits, I faced a decision: head for a certain deer stash, location undisclosed, and wait for the fading light of dusk to coax some meat in my general direction, or glean from a patch of collard greens and kale. The owner of said patch of greens was ready to be done farming for the year, and with the season’s final market already past, she had no way to sell her greens. The irony is that once autumn gets a few frosts under its belt, the greens are sweeter than they’ve been all summer. She had invited me to come take all the greens I wanted, and warned me that I’d better do it quick, before she plowed the patch into the ground. While I really wanted to go post up for a chance at some red meat, this sunny afternoon might have been my last and most pleasant opportunity to put away massive amounts of leafy greens. And unlike the deer, for which I’d already been hunting unsuccessfully for weeks, these greens were a sure thing. When harvesting from a patch that’s about to be plowed under, you can go really fast. You don’t need to be careful with the plants; you can spin through that patch like a dervish on crank. Especially when you get to go hunting if you finish soon. In 20 minutes, I had about 50 pounds of greens—more edible weight than I could hope to get from an average-sized deer. And shooting a deer is much more difficult. And when you add up the time and expense involved in hunting, it just doesn’t come close to the yield of putting away some greens. I’m not arguing against hunting here, but when you add up the numbers, a well-balanced food stash—and a well-planned food acquisition strategy—has to include some greens. Even if you have to purchase your greens, the cost of buying and freezing in summer versus what you’d pay in winter is significant. A steady stream of research suggesting that green leafy vegetables are about the best thing you can possibly eat supports my argument: It makes sense to invest in good, local greens in autumn, and stash them away to use until the new leaves of spring emerge. I’m about to give you some winter salad ideas for those frozen greens. But if you didn’t put any away, or if you’ve already run out, by all means go buy some greens to practice on. Hopefully next year you’ll think ahead. That afternoon, following the unsuccessful hunt that followed my green gleaning, I boiled a big kettle of water and blanched the greens, in batches small enough that the water never lost its boil. After two minutes per batch, I fished the leaves out with a slotted spoon and plunged them in a cold water bath to stop the cooking and fix their bright green color. Four months after those leaves were drained and frozen in freezer bags, they’re still bright green. My default method of using frozen greens is to sauté them in olive oil with garlic and soy sauce, but lately I’ve been on a salads kick. Although they’ve been blanched, thawed leaves can be treated as if they were raw. And these same salads can be made with raw, fresh greens from the store, if you have to purchase them. Mainstream American cooking could stand to incorporate more , because right now our winter veggie usage is in a rut. The typical American salad, which is a study in the power of habit, typically includes some bland variety of lettuce, like iceberg, maybe some onions—but not too much lest they affect our sterile breath—and red things that look like tomatoes. I’m sick of fresh tomatoes in winter! The modern sense of entitlement to these cardboard imposters is what’s wrong with our food system in microcosm. They embody the exploitation of human laborers, the environmental toll of chemo-monocultures, and the emissions associated with producing and shipping those produce all over the country. One thing they don’t embody is flavor. In a well-balanced salad made with fresh ingredients, fresh tomatoes can add a welcome burst of sweetness and acid, giving the salad contrast and diversity. The flavorless tomatoes of winter don’t do that, and they’re unfortunately added to too many salads made on autopilot. Currants and raisins, soaked overnight in white balsamic vinegar, can fulfill the function of tomatoes elegantly. These rehydrated fruits of summer can hold their own in a salad of frozen greens dressed in soy sauce and rice vinegar, and tossed with pine nuts or sunflower seeds. Fresh onions, another crop you should have no trouble storing deep into winter, add a fresh zing to your winter salad as well. To make a winter salad from kale, collards or chard, cut the thick stem out of the leaf’s center, then slice the leaves into thin strips before tossing in the dressing of your choice. Use the stems later, perhaps cooked in a winter stir-fry. For an Asian-style winter salad, toss your thawed leaves with two parts soy sauce, one part rice or cider vinegar, and one part olive oil, then sprinkle liberally with gomasio, a Japanese seasoning made from sesame seeds and salt. For a Mediterranean twist, toss your thawed leaves with balsamic vinegar, salt, feta, toasted pine nuts and sun-dried tomatoes that have been marinated in olive oil—sun-dried tomatoes in olive oil being an infinitely superior alternative to winter-grown fresh tomatoes. If you serve any of these salads alongside meat, or any other rich food, the fiber in the greens will help push the heavy stuff through, cleaning your pipes like an intestinal Brillo pad. And these salads are a reminder that the fresh greens of summer are getting closer each day. Next summer, maybe you’ll stash more for fall. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel