|

| ||

| It’s a Bhutanese ‘thing’

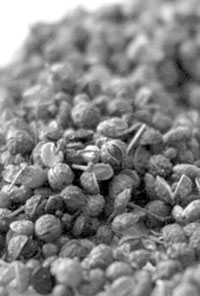

by Ari LeVaux At the farmers market last week I passed on some beautiful green beans for no reason other than my own lameness. In fact I wanted those beans. They looked good and had great flavor (I tasted one), but I was in a hurry, I couldn’t think of anything to make with them, and I didn’t want to make a pointless impulse purchase. My regret bugged me for the rest of the day and was re-aggravated a few days later when my friend Tempa invited me over for dinner and proceeded to shame me with his prowess at cooking with our local ingredients. Tempa is from Bhutan, a tiny country on the south slope of the Himalaya between India and China. Though he was so far from home, many of the ingredients at our local farmers market were familiar to him, including the fresh green beans I had failed to buy. The only ingredient Tempa needed from his part of the world was a spice he calls “ting-ee.” “How do you spell ‘ting-ee?’” I asked. Tempa thought for a moment and said, “T, H, I, N, G.” Thing is the seed husk of Xanthoxylum alatum, a plant that grows in many of the lower valleys of the Himalaya. It has a tangy taste with lemony aromatic overtones. The thing plant is known as the “toothache tree” in the highlands of India, thanks to the mouth-numbing sensation thing causes when chewed. Thing is also popular in China, where its name translates to “mountain pepper,” though it’s unrelated to black pepper. In the United States, thing commonly goes by the name “Szechuan pepper.” In Szechuan cuisine – which, like Bhutanese food, is known for its heat – thing is ground together with salt and toasted in a wok to create a mixture that’s used as a condiment to accompany pork, duck or chicken dishes. Thing is also an element of the famous Szechuan five spice powder, along with anise, fennel seed, clove and cassia (or cinnamon). The Bhutanese name of the dish Tempa cooked for me translates as “beef curry,” though it doesn’t resemble most people’s idea of curry. In Bhutan the words “curry” and “gravy” both mean sauce. In this case, tomato sauce. To make Tempa’s beef curry, begin with some cooking oil in a pan, and add half a pound of beef (any red meat will do), cut into chunks. Brown the meat on medium heat, remove from the pan, and set aside. Then add 4 cloves of garlic, 1 medium onion, and 2 large tomatoes – all minced. Cook over medium heat. “When it looks like it will melt, add the beef,” Tempa instructs. In other words, when the tomatoes release their water, add the meat. As the curry simmers slowly in the pan, add water as necessary to keep it from burning or getting too thick, and to keep the meat covered. Keep simmering until the garlic, onions and tomato blend into a consistent sauce and the meat gets soft. Once the sauce has merged and the meat is tender, adjust the seasoning with salt and add chopped green beans. Then, with a mortar and pestle or food processor, mash together some thing (a tablespoon, more or less, to taste), ginger (about a cubic inch, minced), and a few cloves of garlic, minced. Stir the garlic/ginger/thing mixture into the pan, cover and cook for about a minute. Then add chopped “coriander leaf”—aka cilantro. Serve with rice. Bhutanese food isn’t known for its complex spicing mixtures. Salt is common, and if you ask for pepper you get thing. And while it’s one of the few spices in Bhutan, thing is used sparingly. “You mostly put thing in esay (pronounced ‘ee-say’), or when you want to cook something delicious, like animal hide or stuffed intestines,” Tempa said. Esay is like a Bhutanese version of salsa, a red paste served alongside the meal and used to add extra heat and flavor. The prospect of extra heat may seem absurd to anyone who’s experienced the regular heat of Bhutanese food, but on the other hand, the mouth-numbing properties of thing might help neutralize the burn. To make esay, lightly roast some dried red peppers over fire or in the broiler, then crush them into small pieces, by hand or with a food processor. Alternately, you can use chili powder or crushed red chilis, just make sure you end up with a quarter cup. Mince a small onion, a medium tomato, half a bunch of cilantro, and a cubic inch of ginger. Briefly toast a tablespoon of thing in a hot pan and crush it. Mash everything together until it’s a thick red paste, adding salt to taste. Esay is great with rice, animal hide and other Bhutanese specialties. It’s also amazing with the morning scrambled eggs. Your friends will love it, and if they ask about its uniquely tangy flavor, tell them it’s just that special thing that you do. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel