|

| ||

| Taking a chance on change

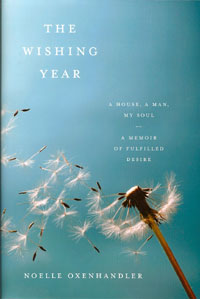

by Katherine Leiner The Wishing Year: An Experiment in Desire by Noelle Oxenhandler; (287 pages, Random House, 2008, $24) The second time I read Noelle Oxenhandler’s The Wishing Year, (which is about her year’s experiment in desire, or “Putting It Out There,”) instead of concentrating on her lovely writing (the perfectly chosen adjectives, the finely tuned sentences that strike their “arrow’s sharp point,”) I focused on whether or not she had fulfilled her thesis successfully. I looked between the lines and began to relate to the “heart” of her matters and thus, my own dreams, hopes and desires began to unfold. Oxenhandler tells us that one New Year’s day she was taking stock of her life and found that she was alone after a long marriage, seemingly doomed to perpetual house rental, and separated from the spiritual community that once sustained her. She had little left to lose. In the past she’d been a skeptical dreamer and to make a wish for personal gain or benefit would have bordered on heresy. Raised by a Jewish father and Catholic mother, Oxenhandler was loaded with superstition and fear. “In its reflection,” she writes, “the book focuses on these fundamental questions: Does a wish have power? If so, what kind of power and how can this power be tapped? Is there danger in wishing? If so, what sort of danger is it and how can the danger be avoided? At the root of these questions is one perennial mystery: the connection between mind and matter, psyche and substance, soul and world.” Heavy. That’s for sure. Oxenhandler’s writing is academically rich and informative while being deeply personal. She presents her thesis through the words of Parmenides from the Sixth Century B.C. and Emily Dickinson (to name only two of the renowned sources that she quotes). She also uses her own personal experiences of friendship, love and loss. She’s enormously generous with her knowledge and her feelings. Unlike the book, Eat, Pray, Love (to which The Wishing Year has been compared), where the heroine is sent to rarified places in the world to “find” herself and is paid by her employer, Oxenhandler gives us a possibility that we can all access and afford, without leaving our own magnificent Rocky Mountain back yard. She asks only (and she shows us the way) to define clearly our intentions – state our wishes clearly and succinctly. And when the world gives us what we’ve asked for, or almost, to look at what we get with gratitude. Even though sometimes we don’t get exactly what we want, if we look at it closely, it’s usually, as Mick Jagger has been telling us for 40 years, what we need. (Back to the writing …) Sure, Oxenhandler’s metaphors are lovely and we are exposed to sentence after sentence of beautiful prose. And if we have read her other work, we know she has written about difficult subjects such as her own spiritual grief at her parent’s divorce in her first book, A Grief out of Season. Among her essays in The New Yorker, in 1993 she wrote “Polly’s Face” about a mother’s darkest fear: the kidnapping and murder of a child, in this case Polly Klaas. In her second book, The Eros of Parenthood, she has taken the taboo subjects of love between parent and child and teacher and child and the ways in which our society has distorted affection and pointed fingers at those who have innocently loved our children. She has spent the last six years with Buddhist teacher/writer Jack Kornfield on his latest book, The Wise Heart. She also teaches creative writing at Sonoma State University in Santa Rosa, Cali. In The Wishing Year, Oxenhandler levels with us about her own process of taking a chance on change: change of attitude, change of heart, change of life. We all long for some of the characters in her book to cross our path and help us to actualize our desires. We move with her as she begins to drop below her Judeo/Christian background, learning that whether divined by a higher force or drawn by the law of attraction, wishes come true. As a student of mediation and Zen Buddhism for more than 30 years, Oxenhandler says, “I’m not interested in talking about myself for the sake of talking about myself. I’m interested in using my own experience to explore an idea.” Although she grew up in sunny California and Santa Cruz (where her father taught French literature at the new UC Campus) she roamed the darker regions of “self-imposed exile” to study comparative literature at Oberlin College in perpetually overcast Ohio. She went to graduate school in the frozen north of the University of Toronto before making her way to the Rochester Zen Center in upstate New York where she met and married her now ex-husband, had a child and drifted back to California in the 1990s. She gravitates toward topics that deal with personal things she’s driven to explore. “A lot of people are rather unhappy because they don’t ever risk discovering the unforeseen implications of their visions.” It’s important to take that risk she tells us. So, should we be careful for what we wish? Yup. Because, to paraphrase Mick Jagger, “You just might get what you want!” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel