|

| ||||

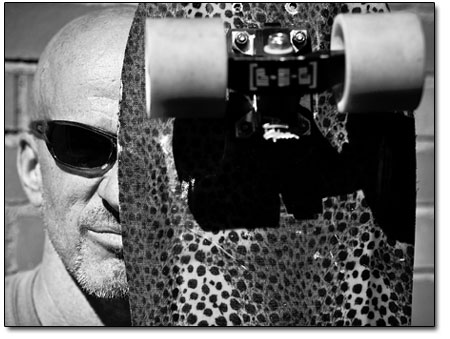

| Skating back into society

by Missy Votel "You never get hurt in the air,” explains George Pappas as he describes the events leading up to his latest injury, a broken collar bone. Rather, it’s what happens when gravity wins, and life comes crashing to the ground, that really matters. It’s a topic that pro skateboarder and snowboarder Pappas knows all too well. For nearly two decades, Pappas, 44, was at the top of his game, winning slalom skateboard and snowboard titles left and right. “Back in the ’70s, I started skateboard racing at the age of 12 and pretty much won every contest I went to,” he says. But then, traditional skateboarding fell out of favor with its fickle American fans and went “underground,” as Pappas tells it. Soon to take its place was the burgeoning sport of snowboarding, at which Pappas, a Boulder native, grew quite adept. “I started out riding a Winterstick with bungee cord bindings and Sorels,” recalls the youngest of 11 children of Greek Orthodox parents. “My mom dressed me in five layers of cotton, and I was good to go.” Several champion titles and sponsorships were to follow as Pappas “lived the dream” of a professional snowboarder in the ’80s and early ’90s. But all that soon to come to an end as well. “By 1991, I was over it, it had become more of a job,” he says. “It became all about the money.” In addition, the ever-present drugs and partying of the pro circuit had taken its toll. Over the next several years, Pappas embarked on a downward spiral as he struggled with his demons. In 1996, he ended up in Durango, where he attempted to start life anew with his then-wife and new son. He got out of racing and started a flooring business. A few years later, the slalom racing scene started experiencing a renaissance of sorts. Thanks to the Internet, his old racing buddies were getting together and breathing new life into the sport. “The old guys started talking and racing again,” he said. “Technology had improved so much and equipment was so much better than it was in the 1970s. Riding a skateboard was now the same as snowboarding or skiing as far as being able to carve turns.” Pappas started to dabble in racing again, and with only five days of practice under his belt, he took a shot at the World Championships in 2002. “I was ready to win, but I didn’t even make the cut,” he said. And while he tried to resurrect his racing career, he found old habits die hard. In 2003, he landed on the wrong side of the law. After several trips in front of the District Judge David Dickinson for other infractions, Pappas was convicted for writing a series of bad checks stemming from a drug addiction. “It was my worst nightmare,” says Pappas. “I spun out. I lost my houses. My business. I got arrested.” Prior to sentencing on the fraud charges, out on bond and down on his luck, Pappas decided to try his luck at a race in Breckenridge. Using a donated skateboard from the Boarding House after his was stolen from Taco Bell, he hitched a late-night ride to Summit County. He made it to Breckenridge by 8 a.m. on race day, but gravity once again intervened. “I busted my collar bone riding down to the race course.” More bad luck was to follow. In January 2005, Pappas, who was expecting an easier sentence at Hilltop House as per a plea agreement, had the book thrown at him. Instead of staying in Durango, he was sentenced to three years in state prison. With 13 months of his sentence already commuted in La Plata County, Pappas was sent to a minimum-security prison in Delta. However, after a year, he was given a choice: continue serving out his last year in Delta or be moved to a private, medium-security prison on the Front Range and get six months’ time knocked off.

“This place was basically designed to reintroduce criminals back into society, and they thought I was a good candidate. Prisoners take six or seven classes a day,” he said. On the flip side, it was a bigger, more-controlled facility, with more of the ills associated with prisons, including gangs, drugs and violence. Pappas, however, decided to take his chances. Over the next few months, he quickly learned to live by “the code” and prove himself in more than one jailyard brawl. “I was three for one,” he recalled, not one to sugarcoat the experience. “It’s wrong, but it’s the code, and you gotta live by it. Once you show you’ve got heart, they’ll leave you alone.” As bad as the experience was, Pappas turned it into an opportunity. “If you’re motivated to learn, that’s the place,” he said. “I took everything they gave me and ate it up.” In fact, toward the end of his sentence, Pappas found himself teaching a course on parenting, of all things. “Eighty percent of the men in there were fathers, but there was no fatherhood program,” he said. When he brought this to the attention of prison officials, he was shown a stack of books and a curriculum. “I ended up running the fatherhood program for the last three months. Basically, they didn’t have enough money to hire someone to teach it, so I did it.” Once out on parole, Pappas returned to his home town of Boulder. He was – and continues to be – clean of drugs and focused his attentions where he left off at the Breckenridge race. “The whole time I was sitting in jail, I knew I could come out and do this,” he said. In yet another strange twist in his life, he came upon two teens skating slalom on the streets of Boulder. He befriended them, and a unique mentorship grew. “I met these two 15-year-olds and they were way into the sport,” he recalls. “I teamed up with them and we skated every day for a year.” Under Pappas’ wing, the two boys, Martin Reaves and Zak Maytum, became the No. 1 and 2 amateur racers, respectively, in the world in 2007. The two proteges, now both 17, have since gone pro and beaten their guru at least once this year. However, Pappas can still hold his own. In 2007, he ranked fourth overall in the world, and earlier this year, he had two first place finishes, one a hybrid race in Morrow Bay, Calif., the second in the tight slalom (his “signature event”) in Hood River, Ore. He went on to place third in the giant slalom at this year’s World Championships, held in Gothenburg, Sweden – a trip funded by Pappas’ skating buddies. “George was one of the biggest ‘rookie’ surprises for me when I visited the Worlds last year,” wrote fellow racer, Jani Soderhall, of France, in a thread seeking donations for Pappas on slalomskateboarder.com. “He’s definitely on my favorites list – good style and fast.” And while Pappas waits for his collar bone to heal, an injury sustained at the end of his European tour this summer, he’s not sure if he’ll return to racing or not. “I really love racing, and I need to stay in the gravity industries for my sanity, but it’s not the most important thing in my life right now,” he said. “It’s funny, in my 20s I went around looking for the steepest thing to ride, and in my 30s, I spent all my time working on floors to keep them level and flat. Now I’m just looking for balance.” What Pappas is sure of is repaying his debt to society, him family and the Durango community, where he recently returned to live. “Part of my reason for coming back to Durango is to come back with a clean slate and tell my story,” he said. “When I had fallen, people would avoid me on the street, not that I blamed them. But it was pretty demoralizing. “It’s nice to have another chance. It’s phenomenal that I can be in this position again in my life and be an inspiration to others. I feel super blessed.” For starters, Pappas says he would like to help hone the skills of young local slalom racers. However, he admits doing so is easier said than done, due to lack of legitimate training facilities (i.e. roads and streets with decent grades). “The thing with slalom racing is, it’s illegal,” he said. “You can’t do it at the skate park, and the bike trail is a little tame.” Pappas, who has emceed several races, also sees a future in race promotion. And with the World Championships stateside next year, he dreams of Colorado, and possibly Durango, playing host. “Durango’s definitely on the A list of venues,” he said. “It’d be good to maybe team up with another big event and have our signature event go through downtown Durango so people can hang out and watch.” Aside from skating, Pappas would he would like to share his story with “anyone who’ll listen.” He’s already given talks at Hilltop House and would like to reach at-risk youth. “I’m never going to preach. I just want to help people in making their decisions in the future.” In the meantime, he said he’s working on getting back on his feet, rebuilding his life and mending fences. “It’s not about how far you fall, but how you bounce that really matters.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel