|

| ||

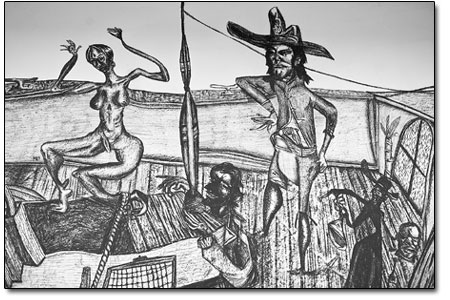

| 'Slave Ship' lands in Durango

by Jules Masterjohn There was no coincidence that as Americans elected their first president of color last Tuesday, Durango artist Mike Brieger installed an art exhibit themed on the black experience in America. Race relations is a topic the artist has been drawing and contemplating since his grade school days growing up in a mixed neighborhood near Detroit. By favoring the subject of African-American struggle as the primary story in his exhibit, viewers will be reminded that Barack Obama will stand in the White House on the backs of countless millions of people of color who have suffered at the hands of imperial powers across the world. For Brieger, remembering the past is a useful tool in keeping the less compassionate impulses – those urges towards greed and denial – in check. Brieger’s drawings, paintings, collage, and sculptures reflect his personal take on the world, yet they speak to broader concerns than racism or colonialism. Fully utilizing artistic license, his provocative and direct style points to art as metaphor and the artist as decipherer of the human condition. To this service, Brieger borrows from historical art movements for his aesthetic and thematic foundations. In the end, his works shine light on the potential darkness within the human psyche. Take for instance, his conté crayon drawing “Slave Ship.” The above-deck drama portrayed is historically probable, though the artist’s rendering is bizarre, incorporating multiple perspectives of the figures in simultaneous frontal and profile views. The slaves’ bodies are distorted, naked, and shackled, lying, dancing for or being fondled by those controlling the ship. A rectangular shape in the center of the deck is filled with individualized, disembodied heads. He depicts the hold of the ship from above and the artist’s visual shorthand for a crowd of slaves below. Brieger skillfully creates a Cubist-influenced environment, illustrating some semblance of 3-dimensionality yet he also offers a flattened, shallow space adding to the disorienting scene. The viewer sees this “docu-drama” from a floating perspective, high above to witness the scenes yet removed from what lies below. A small piece of paper with typed words reads, “Turn off the oven, close the popular book that grows in your body.” A nod to the Dadaists, the Haiku poem written 15 years ago, was spontaneously mounted below the picture, to “keep it fun” for the artist. Many of the works throughout the exhibit are paired with a Haiku. In the drawing “I was from the alligator clan,” a large black man – whose naturalistic muscular body is pierced, bound and posed like a Christ figure – is being tortured at the hands of ball cap clad smaller black males. The torturers’ bodies are rendered in simple form, reduced to the bare minimum of shapes. The victim looks calmly out at the viewer as a diminutive White master looks on. In the background, two severely distorted black females stand, being watched by a uniformed white guy. There is much more happening in this scene, and much more than meets the eye. In portraying the victim’s body as real and life-like, the viewer is invited to identify with the victim and his suffering. The oppressors, on the other hand, have feeble and diminished bodies, unreal in their proportion and scale. Brieger creates a congruous relationship in the condition of the body and that of the mind, metaphorically implying that only an impoverished being could inflict such pain and humiliation on another. Utilizing distorted formal elements, exaggerated stylistic devices, and emotionally charged narratives, Brieger places himself in the company of the German Expressionists. Their work was a response to a world too inhumane to comprehend, having witnessed the horrors of two World Wars. With his ability to translate physical form into psychological function, like the Expressionists before him, Brieger exposes the human condition so the viewer can be touched by a truth one has not lived. If one simply reacts to his potently perverse pictures, Brieger could be termed a “bad boy artist” – except that his inner nature reflects none of the required f%&#-the-world attitude. A humble, sensitive and gentle human, he is a serious contemplative who expresses his insights in ways that fit with the modern world. His images are fragmented, as is the outer world; they use sex and violence to frame experience; his art is made of the mundane materials found in daily life. Like our inner worlds of thoughts and feelings, his art is not tidy but rather a jumble of ideas with their associated emotive power. For Durango, this is a provocative show, and it will not please those who think art should sit quietly on the wall and look pretty. “Ugly can be beautiful but pretty can never be,” he says. Using the genres of street art and back alley social realism found in urban areas, Brieger brings the larger world of in-your-face visual critique home to gnaw at the seams of what it seems. Brieger chooses to be in Durango, and we are fortunate to have an artist willing to go against the grain of local tastes, polite habits, and comfortable lives. “As an artist, there’s a desire to just do your thing, so I do mine in Durango knowing that there is a larger thing out there,” he says. Brieger’s psycho-socio themes and slap-dash style of presentation may act as diversions for some and doorways for others to the underlying theme of this exhibit. Though Brieger portrays a specific ethnic group in relationship to another, his use of narrative, metaphor and artistic style are conductors of a deeper message. The artist asks us to look inside ourselves, to acknowledge and see our own internalized victim and its relationship to the oppressor within. Beyond the color or shape of our skin, we all suffer and we all cause harm, and this is Brieger’s very skillfully presented message. • A reception for the Mike Brieger mixed media exhibit is set for 5-7 p.m. on Nov. 14 in the Art Library upstairs in the Durango Art Center, 802 E. Second Ave. His work will be on display through the end of December.

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel