|

| ||

| Good, clean and fair

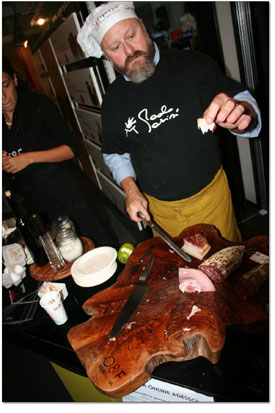

by Ari LeVaux Turin, Italy – The Slow Food movement’s biennial convention, which just ended, consisted of twin events called the Salone del Gusto (Taste Fair) and Terra Madre (Mother Earth). To Slow Foodies, food is more than caloric gas with which to fill your physiological tank. Food should be savored, they believe, and the production, preparation and consumption of food are sacred. The movement, which began as a protest against the building of a McDonald’s restaurant near the Spanish Steps of Rome in the late 1980s, now counts more than 100,000 members in 132 countries. It literally took days for me to wander the vast space of the Salone del Gusto, slowed down as I was by the event’s 180,000-plus attendees and a bewildering array of artisan food from around the world. A few highlights: Wild strawberry jam with rose petals from the high Alps. German garlic flowers marinated in artichoke oil. Tuscan pig-head sausage with lemon and orange. Cold smoked sausage that had the raw mouth-feel of sushi. Honey made from chestnut flowers. Peruvian tomatillo marmalade. Transylvanian pickles. Twenty-year-old mead. Twenty-five-year-old balsamic vinegar. Myriad fancy cheeses. Prosciutto up the wazoo. An egg from a flock of hens raised on milk from its own dedicated herd of goats – the egg was soft-boiled and served with white truffle shavings. And at every turn: vino, vino, vino. Thousands of people milling about, stuffing their faces, and getting their collective buzz on is a beautiful thing. Which is why I was surprised to hear Slow Food’s founder, Carlo Petrini, tell me, “I’m sick of masturbatory gourmets, people who smell a glass of Bordeaux for half an hour and speak divinely, as if they are priests, ‘Oh, it has the wonderful smell of horse sweat.’ No more cooking shows, please; no more stirring pots on television.” His comment embodies an important evolution in the focus of Slow Food. While the movement started virtuously as a response to the ills of fast food, in the U.S., it’s been criticized as a sort of elitist supper club for people with the means to indulge leisurely dinners laced with esoteric musings. While many Slow Foodies are aware of the environmental, political and social consequences of food production, in many convivia (as the local chapters are called) these topics have served more as dinner conversation than rallying cry. But more recently there has begun a focused effort to make social, political and environmental activism part of the Slow Food agenda. Alice Waters, chef, author and matriarch of the Slow Food movement for decades before it had that name, reminded the 800 members of Slow Food USA who made the trip to Turin that Slow Food must uphold the values of . “Good food is a right,” she said, “and not a privilege.” Waters introduced the new president of Slow Food USA, a farmer named Josh Viertel who told the group “The problems in our food system disproportionately hurt poor people and people of color. These are the people who are less able to access the benefits of Slow Food. I’m going to change this organization so that it’s not just about pleasure. We are going to become a social justice organization. I want to live in a world where the food is good for the people who eat it, the environment and the people who grow it.” This widening focus is also evident in the structure of the twin events. While the Salone del Gusto maintains the established Slow Food values of top-notch artisan food, Terra Madre gathered 8,000 farmers, businesspeople, educators, students and activists for discussions and workshops on responsible, sustainable and fair food-production practices. The passageways connecting the two events were lined with stands celebrating the street food of the world, serving dishes like tripe sandwiches, deep-fried stuffed risotto balls, shish-kebab and fried calamari. This year for the first time there was also an emphasis on textiles and music – which played continuously on three stages. “Natural fibers music are part of the farm economy, so they need to be here,” said Carlo Petrini. “Agriculture is not just an economic sector, like steel. It’s life. It’s rapport with the land. It’s social, and sacred. This is about identity. That’s why we didn’t want professional musicians playing so-called ‘world music’ that’s stolen from farmers. We wanted real farmers playing real farm music.” President Viertel told me he’s determined to bring more young people into the movement and thinks the shift toward activism will tap into the natural idealism of youth. “Young people don’t want to inherit the world as it is, and they have the largest stake in making it better, he said. “Youth are leading the sustainable food movement.” I shared a Sicilian beef spleen sandwich with Waters, who agrees with Viertel’s belief in the importance of including young people in the Slow Food movement. Her most recent book, Edible Schoolyard, is about putting kitchens and gardens in schools. Connecting kids with food opens the door for a host of important realizations, she believes, including a comprehension of the struggles farm workers face. “We need to include the farm workers at every discussion,” she said. “We may understand good food, we may understand clean food, but we don’t understand fair food. Asking for a few pennies more for tomato pickers isn’t enough.” The Salone del Gusto and Terra Madre were testimony that food issues connect to many of the most pressing issues we face. This, plus the fact that we all love food and we’d die without it means we need to be thinking deeply, urgently and yes, slowly, about bringing food back to the center of our lives and culture, where it belongs. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel