| ||

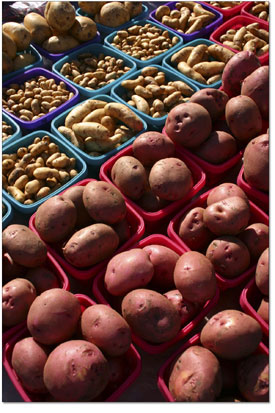

Farmers market theory

by Ari LeVaux The marketplaces of the world have always been charged with the energy of trade, an activity with its own language, which, like the language of love, is hard-wired into humanity. From the perfumed bazaars of Timbuktu to NASDAQ’s digitized stock exchange to the farmers markets blooming across the USA, visceral energy exists anywhere you find deals being made. Solar radiation, human effort, gasoline and other forms of energy are folded into goods as they’re created. And gatherings of people, like gatherings of plutonium, can reach a critical mass expressed in a palpable buzz. After a long winter, the farmers market is the place to catch up on gossip, find out who got pregnant, and people-watch from behind sunglasses over a cup of coffee. And then of course there’s the energy of trade: the negotiations, the sales pitches, the wheeling and dealing as participants search and haggle for the best possible deals. But many shoppers rarely pause to consider a certain mathematical law of the universe: for every great deal someone gets, someone else gets shafted. Last year, a shaggy guy with a South American man-purse tried to shaft a farmer friend of mine – I’ll call him Farm Dog – at his market stand during a brutal heat wave. “He handed me some broccoli. I weighed it and told him, ‘that’s 3 dollars in broccoli,’” Farm Dog recounted. “How about $2.50?” came Shaggy’s surprise counter-offer. Shaggy was trying to work that farmers market like a gringo bargaining for the local price in the mercados of South America, where cool, cheap goods are the rule, and haggling is expected. But Farm Dog, after months of searing his shoulders carrying hot irrigation pipe and hoeing deliriously in the crushing sun, was in no mood to bend over so Shaggy could keep a little extra beer money. “No, not for 2.50,” he said, restocking his broccoli. “Who’s next?” Driving a hard bargain in order to defend your interests is noble, while pushing hard for a bigger share is lame. But before you scold Shaggy and his ilk, ask yourself how fair a trader you are. When was the last time you bragged about scoring a “steal” of a deal? Every time you wheedle a few extra pennies off the price, you’re cutting into someone’s profit margin – the margin that makes the effort worth their while. Some justify this bargaining between buyer and seller in Darwinian terms, arguing that competition and natural selection produce strong survivors. This brand of law-of-the-jungle economics finds its epitome in the world’s equities markets, perhaps the greatest money-laundering outfits of all time, where every time someone buys low and sells high, someone else, or some combination of people, essentially bought high and sold low. Thus, the sins of capitalism are washed into a sea of anonymous digital assets. A good farmers market, on the other hand, thrives on cooperative and face-to-face relationships between farmer and customer. In order for the market to succeed to everyone’s benefit, all stakeholders need a fair deal. Markets can start off slowly in spring, before the produce comes on strong. In the meantime, some stands offer mostly plant starts for sale, and the action can seem about as exciting as watching paint dry. On such days growers might offer specials, but not always for business reasons. Sometimes, after a long winter, a farmer could use a little friendly face-time with a customer. Remember: More likely than not, they didn’t get into the business to get rich. They want to grow food and feed people. Sometimes, a little friendly chit-chat brings unexpected rewards. “If someone just points to a tomato plant and grunts, I’ll grunt back and sell them the plant,” says Farm Dog. “But if they ask, ‘hey, is this a good tomato plant?’ I’ll take the time to help them figure out what they’re looking for. Maybe I’ll say ‘that one’s OK, a nice specimen of a fairly pedestrian variety. But see that scrawny one? It’s our last Sungold plant. It doesn’t look like much right now, but once it takes off, it’ll grow huge and make tons of the tastiest yellow cherry tomatoes you’ve ever had.” He’s noticed that many people, perhaps playing defense against cutthroat vendors, seem skeptical of his sales pitch when it’s directed at them. But the person standing in line who overhears the same pitch will be more likely to believe it, buy that scrawny Sungold tomato plant, and reap a summer’s worth of juicy rewards. A good indication of vendor’s trustworthiness is the extent to which he or she cares about the future of the baby plants they’re selling, evidenced by the extent of cultivation guidance they give. Advising you to “stick it in the ground, it will do great” is less compelling than “leave it outside in the pot a few days to harden-off before planting,” or even “plant in a shady place.” In the case of food for sale, discussing how to cook this or that can reveal the farmer’s commitment to your satisfaction, and offer a doorway not only to a good meal, but to a lasting relationship with your farmer as well. So before you congratulate yourself for driving such a hard bargain on a bag of fresh spinach, take a look at the farmer’s leathery hands, and note how those hands have been tattooed with dirt so you can eat. Instead of going for the jugular, you could tell the farmer to keep the change. It would be a small but well-received gesture, an example – however token – of team spirit trumping competition. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel