| ||||

Animal crackers

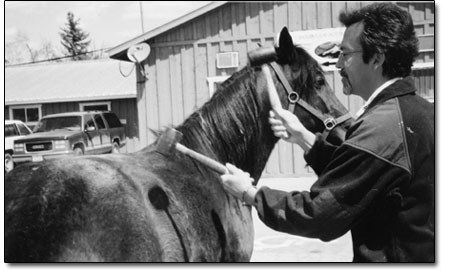

by Stew Mosberg Two of the treatment areas had cracks in their oil-stained concrete, and a third was covered with dust and strewn with hay. None of them were what you’d expect to find when visiting an alternative medical facility, unless the doctors are equine chiropractors and their patients, full-grown horses. Dan McClure was working on a Peruvian paso named “Caro” in the parking lot of his Bayfield office. Jay Komarek adjusted two champion cutter horses outside his “Café of Life” office on Highway 3 – one of them 14-year-old “Cash in on Okie,” valued at $40,000. Obviously, keeping “Okie” healthy makes good business sense. The third chiropractor, Bill Hampton, was treating “Viggos,” a 10-year-old former thoroughbred, at a horse show in Aztec. The chiropractic profession is more than 100 years old and is much in demand in Durango, which might explain the more than 40 listed in the telephone book. Among them are several who also treat animals. With patients that include a virtual Noah’s Ark of species, doctors of chiropractic medicine can enhance the life of just about every genus, from our town’s numerous dogs and cats, to the equally proliferate cattle, sheep, horses, llamas and prize pigs. Even zoo inhabitants such as tigers, birds and reptiles, have undergone chiropractic adjustment. It might be easier for the layperson to comprehend working with smaller creatures, but how, for instance, does one manage to adjust something as large as a horse, elk or rodeo bull? Carefully, to be sure, and since animals can’t tell you how they’re feeling, owners generally rely on behavioral changes to determine the state of wellness. A rider might notice the horse acting abnormally; being head shy, pulling in one direction, not taking a lead, even a change in hair color along the body; any of these could be a clue. Adjusting an animal and correcting for an injury is accomplished using several techniques. Most animals passively accept the preliminary examination and the subsequent adjustment without signs of resistance. Yet, as with humans, when extreme discomfort does exist, the chiropractor will recommend waiting before treatment is administered. Animal chiropractic medicine is not a replacement for regular veterinary care, and to ensure there is no other condition causing the symptoms, it is advisable to consult a veterinarian prior to seeking treatment from a chiropractor. When administering to large animals, size doesn’t really matter as much as one would think, because the adjustment is made to a specific point on the animal’s spine. With the equine set, for instance, back and leg injuries are very often related. McClure graduated from Palmer College of Chiropractic Medicine in 1982, but they didn’t teach animal procedures there. He is largely self taught and treated his first animal while still in school. It led to a life-long pursuit of animal care and research, including unearthing bones for study and experimentation. While maintaining a busy human practice, particularly with Olympic and elite athletes, McClure has also treated thousands of horses, as well as a tiger cub, cattle, llamas and a rodeo bull, aptly named “Bodacious,” who had to be placed in a squeeze chute so McClure could adjust its neck using mallets.

According to McClure, “A sense of touch,” is vital because an animal can’t tell you what is wrong or how it feels, and the practice, he continued, “is sort of like learning to read Braille.” As he treated the Peruvian paso Caro using his hands, and at times, rubber mallets, he worked the horse’s legs, head and spine, while being careful not to get stepped on or jostled. Caro didn’t seem to mind at all. Hampton, who is also a saddle fitter, was treating thoroughbreds at two San Francisco race tracks before moving to Colorado. Today he works on a number of horses that are barrel racers and cutters. The methods used by all three of these chiropractors are similar in approach, but neither Hampton nor Komarek use mallets. They prefer a hands-only approach. Observing McClure using the mallets, it didn’t appear to hurt the horse, nor was it anything like playing a xylophone on the animal’s spine. In fact, the mallet technique isn’t much different than using the “activator” that is often employed by chiropractors on people as well as animals. As Hampton worked, he moved slowly and spoke articulately about each step as he went along, reassuring and informing the owner of what was taking place and what he was finding. “The way I see it,” he says, “if you’re not asking me questions, I start asking you questions.” Like McClure and Komarek, Hampton also teaches. His gentle manner gains total confidence of the horse; lifting here, poking there, stroking, checking for signs of discomfort, and manipulating muscles, and bones, as he goes. In the course of the exam he approves of Viggos not being shoed and prefers it for most horses. Viggos was suffering from numbness, and Hampton suggested that it might take up to three visits to correct. He also commented that when a horse experiences numerous maladies, treatment will improve the condition almost immediately, but the oldest problem will take the longest to heal. X-raying an animal of such considerable size is extremely expensive, so a thorough examination is conducted prior to beginning the first treatment. Beyond the emotional attachment to one’s pet, economical reasons drive many chiropractic treatments. Around Durango, cattle represent a major investment and keeping livestock healthy has obvious benefits. McClure mentioned one prize seed bull whose semen output greatly increased as a beneficial side affect from the treatments; the by-product of which added immensely to the bottom line. Hampton spoke of his successful bi-weekly visits to the race track stables where the speed of the horses he treated increased significantly, turning them from also-rans into winners. Komarek, in addition to delivering care to his human clients, has been adjusting animals for 30 years and is also a founder of the American Veterinary Chiropractic Association, one of the few accreditation institutions in the country. He was raised in a chiropractic family, where his father and two uncles were chiropractors. “As a child, I learned first hand the benefits of chiropractic care,” he says. Speaking of his experiences treating cats, dogs and horses, he notes that animals recover more quickly than people. “I believe the reason for this,” he remarked, “is that there is no chattering mind that gets in the way of healing.” As with most chiropractors, Komarek achieves positive results by “clearing the central nervous system of tensions that build up energetically and physically. The rest is up to the body,” he says. Adjusting a horse doesn’t require force. In fact, Komarek says, “It’s not about force, it’s the direction (of the manipulation)...and knowing the mechanics.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel