|

| ||||

| Beyond organic SideStory: A bigger, better market: Durango Farmer’s Market opening bell this Sat.

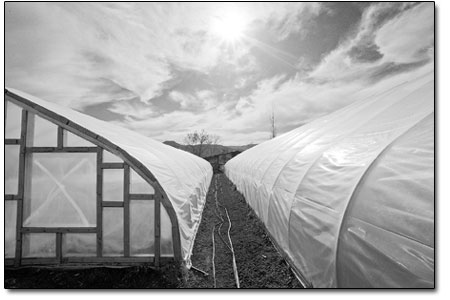

by Missy Votel To be or not to be organic, that was the question among many of the nation’s farmers in years past. But with the growing corporatization of organic agriculture, that question has become increasingly complex, with the core of the once-small organic movement struggling to return to its roots. “We like to refer to it now as ‘more-ganic’” said Jim Dyer, a Marvel-based grower and project director of the Southwest Marketing Network, a nonprofit group dedicated to increasing connections and opportunities for farmers and ranchers in the Four Corners states. “One of the things that troubles the organic community is the size and scale of some organic operations. They’re huge, and that is a concern.” With national organic food sales up at a clip of nearly 20 percent a year, corporate giants have taken notice. In the last few years, small operations have been gobbled up by big names such as General Mills, which now manages Cascadian Farms and Muir Glen; Kraft, which owns Back to Nature and Boca Foods; and dairy giant Dean Foods, which bought out Horizon and Silk. And while the growth in organics is positive in many ways, it is also seen as a doubled-edged sword that raises questions about homogenization and resource consumption in getting those products to farflung markets. Dyer, whose group is responsible for publishing a directory of local and regional producers, among other things, recently attended the network’s annual conference in Santa Fe. There, talks centered on how organic and small-scale growers can reclaim a movement that has grown beyond its original intentions. A survey of growers at the conference found that only a small number in the four-state area have elected to go after the official U.S. Department of Agriculture organic certification, an often costly and arduous process. Closer to home, Chimney Rock Farms, near Pagosa, is the only USDA certified organic grower. A handful of others have opted for the Certified Naturally Grown label, a grassroots, streamlined alternative to the USDA certification that is geared toward small farmers distributing through local channels. For the most part, however, growers are exploring other methods to convey their principles, which mostly center on the “locavore” tenets of locally grown, seasonal, sustainably produced food. “If you are a family farm, then you should hang up a sign saying that you are a family farm,” Dyer said. “We are encouraging producers to tell their stories. Organic is just one part.” Other selling points could include a smaller operation, humane treatment of livestock and animals, consideration for wildlife, and a farm that is child friendly and has been in the same family for generations. “All that is important for marketing,” Dyer said. “Some people pit local versus organic, but we should ask for, demand, both.” However, this is not to say that federal organic designation is not vital to certain producers. For growers who sell their products online or use in other organic products, USDA certification is important if not mandatory. “For example, Foxfire Farms decided it was worth it for them to become certified,” said Dyer. “When you’re selling online or over distances, it can be a huge benefit.”

Bill Manning, owner of High Country Foods (formerly Kiva Orchards), a manufacturer of organic fruit products near Dolores, said he recently completed the stringent organic certification process. “I think of it as handling nuclear material,” Manning said of the intense scrutiny. “The inspector was there for seven hours, inspecting the facility and going through records. Every ingredient you use has to have a paper trail that is perfect.” For Manning, who was forced to give up his 42-acre orchard near Hovenweep a few years back after a string of bad seasons, gaining organic certification for his operation was a natural extension of his growing practices. “I’m trained as an ecologist and naturalist,” he said. “I believe there has to be some sense of vibrant balance and giving back to the world.” He said that at the orchard, it used to be common to turn up pot shards from the ancestral puebloans who lived on the land centuries ago. “I thought, if I can just treat the land well, the next person can use it and get something out of it, too.” He said overall, federal organic regulations help make for better food and better land. “It has increased the credibility of organic food and increased its fundamental nutritional qualities over conventionally farmed foods.” Nevertheless, Manning said he understands the trepidation some small growers have over the monolithic organic industry. He points to the example of Mountain Sun, a Dolores-based organic juice maker that over 25 years had grown into the country’s second largest organic juice company. “It was scooped up by a large corporation, and what happens? In a year or two, it was moved to California and all those local benefits disappeared. It was a huge hit to the area.” As a result, many organic operations are preferring to stay out of the eye of corporate interests. “For the last few years, there’s been a strong, new dimension of people applying organic practices on a small scale without certification,” he said. “Their feeling is you can do just as good a job and present your food to the community face to face. That way, there’s a connection between grower and consumer, and they can ask, ‘How do you grow this?’ That’s far more than you’ll know about the mystery meat at Wal-Mart.” Susie Maynard, who has run Clearwater Farms, in Hesperus, for the last dozen or so years, said she has seen the issue personally from both sides. “I was certified for three years, eight years ago,” she said. “It was expensive and a lot of work.” She decided to let the certification lapse when she said she lost faith in the process. “One of the inspectors came out and took a quick look around and said, ‘Yep, you’re organic. You’ve got all these weeds,’” she recalled. And while the process has likely become more stringent in recent years, Maynard said she sees no need to go through it again. “It doesn’t seem to matter for my business,” she said of her 3-acre vegetable and flower operation that relies mainly on the Durango Farmer’s Market for sales. “If people want to know, they just ask, ‘Are you organic?’ And I tell them ‘yes.’” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel