|

| ||||||

| Of shouts and whispers

by Judith Reynolds Once again, the Open Shutter Gallery has mounted a provocative, two-person show in its intimate space. The gallery could easily opt for solo exhibits. But frequently, Open Shutter pairs two photographers with very different intentions so viewers can ruminate on a variety of issues. Not the least is “Light, Shadow and Time,” now on view through April. The quiet power of Thomas Carr’s cultural landscapes stir the heart. In contrast, Mitch Dobrowner’s spectacular desert images trigger an intake of air. Carr, staff archaeologist of the Colorado Historical Society, has returned to Durango with a mini retrospective, prints from 1987 to the present. You may be familiar with his work without realizing it. In 2004, he had a major exhibition at the Center of Southwest Studies: “Presence Within Abandonment: Photography, Archaeology and Western Historic Sites.” Some of those evocative prints reappear at Open Shutter in the current show. In particular, look for “Fort Laramie, Wyoming,” a forlorn landscape seen through a crumbling doorway, or abandoned interiors with late afternoon light glancing off stairwells or across peeling walls. Carr’s square-format, black-and-white prints range from mysterious Scottish landscapes to his more recent explorations of Western historical sites. In all, there is a distinct veil of human habitation, a lost presence that gives his images the pull of memory and a powerful sense of time passing. Technically, Carr achieves this Romantic view of transience by inventive compositions and employing the lower range of the gray scale. He has said he prefers to shoot on overcast days. If light intrudes, he may use it for expressive purposes, softening an old path or an abandoned house. Muting the tonality is a deliberate choice, one of many decisions Carr makes to deepen the drama. His true subject is implied presence and the feeling of time passing. Carr rarely, if ever, relies on formula. Instead, he explores each subject for the most telling point of view. His compositional variety has a good deal of subtlety and offers the prospect of discovery. Look closely at what appears to be a casual shot of birds on a rain-soaked street. “Montreal, Canada,” 2004, seems offhand, a mere glance downward on a city stroll. But Carr has carefully observed a handful of pigeons and includes, almost imperceptibly, a pavement fleur de lis, the heraldic emblem of the Kings of France. You know you’re not in Kansas with a carefully observed detail like that.

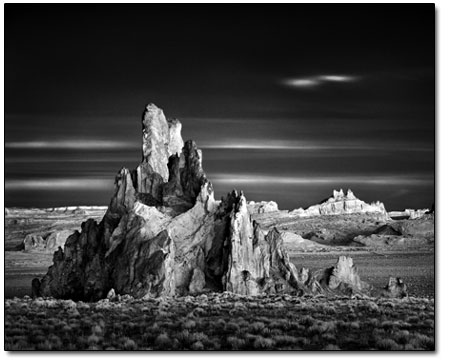

What a contrast to Dobrowner’s prints – bold, forthright, desert images that appear to be artificially lit. He may focus on a monolith or a row of spotlighted rocks in a dramatic, distant vista, but all are surrounded by a sense of impending doom. What a vision of landscape – or moonscape this is. Dobrowner exaggerates brilliant white surfaces and fills them with fine, stony textures. He surrounds his main subjects with cotton clouds and dense black skies. Hyper Romanticism at its best. A California photographer with a New York birthright, Dobrowner admits to developing an addiction to photography when his father gave the teen-ager an old Argus rangefinder. Time, events and a cross-country trip overtook his life, however, and he put aside his personal photography for decades. He and his wife, Wendy, started a family and established a design company in Studio City. Only in the last few years, he said in an interview at the opening, Dobrowner has picked up a camera again. “Today I’m on a passionate mission to make up for 20-plus years of lost time and lost experiences.” Dobrowner’s prints are clearly within the Western landscape tradition. Their pristine technical qualities and vision of the grand view make him a descendant of the late Ansel Adams, the reigning king of the heroic landscape. For his subjects, Dobrowner selects towering mesas or striking formations, like Ship Rock. Fanciful titles more often than not accompany his images – “Acropolis,” “The Crown” – another sign that he’s positioned at a distance from stark realism. Compositionally, Dobrowner tends to center his principal subjects. By employing symmetry in so many images, he may be after a certain formalism, but it can get repetitive. Too many symmetrical photographs make one wonder if he’s relying on a standard device and not exploring other possibilities. In addition, Dobrowner’s preference for extreme high contrast heightens the emotional temperature. Add to this another old photographic trick, vignetting, encircling a central image with an amorphous, billowing black form. The Victorians loved this inner framing technique, partly because it set off or concentrated the central subject. Dobrowner said he doesn’t manipulate the image at all. Instead, he employs standard darkroom techniques, dodging and burning. Shooting with a Sony R digital camera, he also said he’s found the right tool to do what he wants. That his camera has a Karl Zeiss lens doesn’t hurt. With this equipment and the advantages of pigment printing for contrast, detail and those rich blacks, Dobrowner said he is able to recapture on film his intense experience in nature. Dobrowner’s prints are forceful. They shout about the thunder of passing storms, the sudden appearance of light, the strange mystery of the desert. Carr’s prints whisper in a quieter voice – of time passing, of individual places on Earth where humans once lived or passed through. His carefully seen images carry in them a deep nostalgia. You couldn’t ask for two more different approaches to contemporary landscape photography. If you prefer one or the other, what does that say about you? •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel