| ||

A radioactive rush

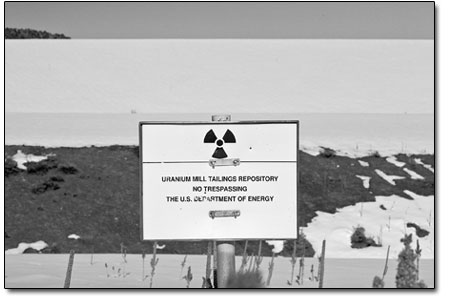

by Will Sands Uranium is showing no sign of cooling down in Southwest Colorado. A second boom is now in full swing in the region, courtesy of high prices for the radioactive ore along with a Department of Energy decision last summer that opens 27,000 acres on the Western Slope to uranium mining. In addition, an energy company is forging ahead with plans to build a new uranium processing facility in the Four Corners region. However, the resurgence is not going unnoticed. Taking the work of activists and watchdogs a step further, the Colorado State Legislature has started to ensure that future mining is done in a safe and clean manner. The Southwest’s first uranium boom arrived in the 1950s with the beginning of the Cold War. At that time, prospectors with mining claims and Geiger counters in hand descended en masse on Colorado’s Western Slope. Many walked away with fortunes, but also left a legacy of mine waste and radioactive tailings in their wake. The prospectors, Geiger counters and mining claims have now returned to Southwest Colorado. The Bureau of Land Management reported 10,730 new filings for uranium mining claims on the Western Slope in 2007. In 2006, 5,205 claims were filed for the uranium rich region. These numbers are up dramatically from the 274 claims filed in 2004. The draw is obvious. With uranium fetching as much as $138 a pound on the spot market, up more than 1,200 percent from the $10/pound price in 2004, prospectors and mining companies are once again eyeing the desert of the Dolores River drainage. Uranium mining got another big nudge last July when the Department of Energy announced its new Uranium Leasing Program. The decision more than tripled the land available to uranium miners – 27,000 surface acres spanning San Miguel, Montrose and Mesa counties. With this in mind, the DOE expects Southwest Colorado will start supplying in excess of 2 million pounds of uranium per year. Energy Fuels Inc., a Toronto-based uranium and vanadium mining company, hopes to take advantage of this opportunity. Energy Fuels is currently planning the construction of the nation’s first uranium mill in 25 years on a parcel not far from Durango. The mill would be sited on 1,000 acres of privately owned land north of Dove Creek in Paradox Valley, halfway between the Dolores and San Miguel rivers. Earlier this year, the company applied for expedited approval of the mill from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Energy Fuels also plans to be a major presence in the area’s re-emerging uranium mining industry and has filed claims for mines in Colorado and Utah. “We are convinced that with the talent and experience we have assembled for this project, our mill will meet or exceed our goals to reach production on schedule and budget,” said George Glasier, Energy Fuel’s president and CEO. Glasier added that Energy Fuels is also confident that it can secure financing for the project, and given the state’s approval, the mill should be open and enriching uranium by 2010. While the economically depressed towns of Nucla and Naturita are embracing the idea of a new industry for the region, others do not share Glasier’s confidence about the prospect. Energy Fuels’ call for “expedited approval” of the project, in particular, has raised eyebrows across the West. Travis Stills, an attorney with Durango’s Energy Mineral Law Center, argued that Energy Fuels Inc. and others are abusing the regulatory process. “The uranium companies are pushing for expedited approvals that evade comprehensive regulatory oversight,” he said. “What this tells me is that the responsible mining and milling of the low-grade Colorado Plateau uranium ore is neither economically nor environmentally viable.” Pointing to the example of Uravan, located not far from the Energy Fuels millsite, Stills predicted another uranium bust with toxic consequences for the Four Corners region. In 1986, Uravan was declared a Superfund site for toxic-waste cleanup, and the once thriving town was literally wiped off the map. “I expect that the current uranium mining boom and the accompanying impacts will go forward for a few more years if the regulators minimize and ignore serious concerns, then go bust and leave Western Coloradans and the federal treasury with the radioactive remains – again,” Stills said. In spite of this forecast, uranium mining watchdogs and conservationists got a big boost recently when the Colorado State Legislature turned its eye on the boom. On Feb. 21, the House Agriculture, Livestock and Natural Resources Committee overwhelmingly passed a bill to prevent unsafe uranium mining. If it survives the House and Senate, HB 1161 would require all uranium mines in Colorado to meet strong environmental and public health protections as a “designated mining operation.” The bill would also require mining companies to restore groundwater quality at injection or “in-situ” uranium mining projects to their original conditions. Conservationists are hailing HB 1161 as a major step toward public health and safety. “The uranium rush could trample our open spaces and poison our waters,” said Pam Kiely, legislative program director of Environment Colorado. “This is a glowing victory to protect our environment from radioactive uranium mining.” A broad range of groups support the bill, including the Colorado Environmental Coalition, the Colorado Medical Society, Environment Colorado and the Alliance for Responsible Mining. Jeff Parsons, attorney of the Western Mining Action Project, concluded that uranium mining can have devastating consequences. If the bill passes the Colorado House and Senate, it will be one more step to ensure that mining and milling in the state are done right the first time, he said. “We’re one step closer to protecting our water from radioactive uranium mining,” Parsons said. “There’s no second chances with the new uranium boom. If we want to protect communities, uranium mining companies need to do it right the first time around.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel