| ||

La dolce vita

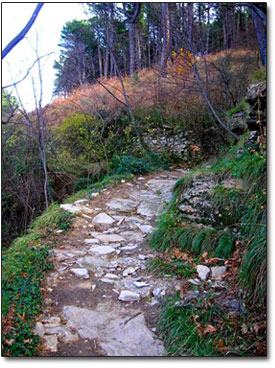

High in the hills, I steer my bike off the paved road and onto a small brick path. Olive and lemon groves fill a hillside punctuated by dark cypress trees standing tall and soldier-straight. Through the dusky winter light, a smoldering sun slides into the expanse of Mediterranean Sea below me. A pink castle tower rises from between two villas, forever guarding the rocky coastline from Arab pirates – pirates who last appeared on the horizon five centuries ago. Since July 2006, Lori and I have been on a two-year working sabbatical from Durango. Our time abroad has been rich with experience, especially living here on Italy’s northwestern coast, in Nervi – the village that now lies below me. Perched on the eastern flank of the once-great maritime republic of Genoa, Nervi’s coast features gnarled rock strata, a tiny harbor and a pedestrian promenade that winds along the water for over a mile. But despite its charms and proximity to internationally known destinations like Portofino and the Cinque Terre, Nervi is almost completely ignored by tourists. In our travels, we’ve been challenged and rewarded by the cultural divide, but in Italy, we’re often struck as much by similarities as differences. And, although the Italian “dolce vita,” or sweet life, is incessantly contrasted to America’s obsession with work and the bottom line, as Durangoans we’re proud to point out that there are places in America where the sweet life takes priority. Nervi carries on in its traditions, a blissful, sun-dappled world of families and neighbors living a sweet life. In the afternoon, couples and families stroll slowly along the seaside promenade. Young children play near the harbor seemingly unsupervised, but in fact closely monitored by an army of grandmothers and grandfathers spying from upstairs windows and watching as they lean against colorful wooden boats in the square. The hills above Nervi are dotted with houses that are accessible only by trail. Some trails have long sections of dirt singletrack, but most rides will also traverse cobblestone, violently eroded asphalt, limestone stair-steps, and, for good measure, actual stairs. I round a curve and nearly collide with four elderly women walking toward me, arms linked, four abreast. I clamp down on both brake levers to avoid becoming the latest American murder suspect in Italy. “Mi dispiace,” I blurt out awkwardly. They’re silent, needing only raised brows to do the heavy lifting of their disapproval. I dismount, in the process snagging the crotch of my riding pants on my bike seat and nearly falling over. The grandmothers stare stern holes through me. I repeat my apology in Italian, and shuffle away, pushing my bike. That night, at Bar Prosit, we’re attempting to place Durango on a napkin map of the U.S. for our friends who work there, Ivan and Matteo. “So, if someone ask me how to get to Doo-rahngo, I just show them this,” Matteo offers, grinning. “Yes,” I reply. Of course, the fact is, most Italians could no more put Colorado on a map than most Americans could locate Calabria. Matteo pours a Fohrenburger, a nondescript Austrian lager that he and Ivan have become obsessed with. It’s the only beer they have on tap, and they tell me that the bar owner was talked into trying it by an account rep who sells them snack foods. “Who orders their beer from the snacks company?” Matteo asks, with his infectious laugh. “Other bars pick a beer because it’s good. So no one else has Fohrenburger.” Like our friends back home, Ivan and Matteo are quick to exploit the humor in any situation. They have posted a hand-written sign on the outside of the bar that says in block letters, “SOLO QUI: FOHRENBURGER.” (Only Here: Fohrenburger). They have created a Fohrenburger promotion that mocks the lowly brand, (“Write your own ad for Fohrenburger”), and concocted a point system that will reward the patron who drinks the most Fohrenburger with a prize: A case of Fohrenburger. I tell them the story of my near-collision while biking in the hills. They think it’s funny. “Did they say something?” Ivan asks. “Nothing,” I reply. “They didn’t say a word.” Then I tell the rest of the story. At the bridge, I got back on my bike and started into a steep climb. I looked back across the ravine and saw them through the olive trees. All four were turned in my direction, watching me intently as I climbed. There was no mistaking it: they were smiling, and they watched me climb until I was out of view. I might have caught them by surprise, but they were smiling because they recognized my dolce vita, and were glad to share that common ground. Matteo pours another Fohrenburger, and we all exchange smiles. We don’t need to toast; it’s clear enough what we’re drinking to. • –Dave Welz

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel