| ||||

| Contentious energy corridors Regional energy transmission plan draws fire SideStory: Arizona group sues over endangered species

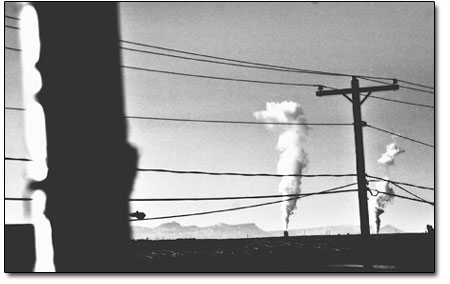

by Will Sands A new series of energy superhighways has been pitched for the West, and one of those electricity and pipeline corridors is slated to pass right by Durango before cutting through Southwest Colorado. The energy network proposal is not going unnoticed, however. Critics and conservationists are charging that the corridors will not only impact and damage public lands, they will open the door wider to proposed coal-fired power plants. Last November, a consortium of federal agencies released its review for 6,000 miles of proposed energy transport corridors covering 3 million acres of public land in 11 Western states. The access strips would open public lands to future electricity lines and oil, gas and hydrogen pipelines, and the agencies allege that the corridors will address growing national energy demands while “protecting the environment.” “From the beginning, we were committed to avoiding the many unique areas and sensitive resources found on Western public lands, wherever possible,” said Assistant Secretary of the Interior C. Stephen Allred. “Designating these corridors will minimize the dispersal of rights-of-way for energy transport projects across Western landscapes.” One of these energy corridors is slated for the Durango area and would cut north from New Mexico between the Ute Mountain and Southern Ute Indian reservations before following the Trans-Colorado pipeline hundreds of miles northwest on its way to Wyoming. The proposed corridor would contain transmission line and/or pipelines, be sited on the San Juan National Forest and cut up to a 3,500-foot-wide swath. “Try to picture a corridor that’s three-quarters of a mile wide,” said Mark Pearson, executive director of San Juan Citizens Alliance. “That’s a bigger area than anything you can imagine. This is basically an immense swath that will just cut across the local landscape.” For the Four Corners, corridors would encroach on areas like the Old Spanish Trail, the West San Miguel Wilderness, Arches National Park and Behind the Rocks, site of the 24 Hours of Moab race. They would be located predominantly on Bureau of Land Management and Forest Service lands, according to the analysis. However, Pearson added that private property crossings are unavoidable and numerous local landowners could feel the pinch of new transmission installation. “The agencies claim it only applies to public land,” he said. “But clearly, you can’t have a long transmission corridor without crossing a bunch of private property. They really haven’t been very forthcoming about that.”

On the flip side, the Colorado Energy Forum, an industry research organization, argues that sacrifices must be made. The group released a recent study finding that upgrades to high-voltage transmission lines in particular are long overdue. “Colorado faces a true crisis if we don’t see significant expansion of the state’s high-voltage transmission grid,” said Bruce Smith, executive director of the Forum. “Not only will we hamstring our ability to meet policymakers’ goal of deploying the state’s huge renewable energy resources, but we also may fall short of being able to get new power delivered to where it is needed.” However, renewable energy has very little to do with the 11 state energy corridor proposal, according to Western Resource Advocates. Tom Darin, the watchdog group’s staff attorney, actually gave the federal government kudos for attempting to minimize the impacts from the corridors. However, he added that the plan is really only a thinly veiled play to the coal-fired power industry. “What’s really driving this whole thing is the huge increase in power demand and the need for new electric power,” Darin said. “When you overlay maps, those energy corridors line up almost perfectly with proposals for new coal-fired power plants in the region. That’s the missing story here.” Western Resource Advocates respects the need for power transmission, according to Darin. However, the group argued that the corridors are based on an “antiquated energy policy” and the government should really be considering alternatives to coal-fired power plants. “Do we want our public lands to feel impacts like habitat fragmentation and noxious weeds in support of yesterday’s energy policy?” Darin asked. “A better option would be to make an effort to have these corridors link up to renewable energy resources.” Nada Culver, of the Wilderness Society, agreed that alternative energy must be a component if wilderness, national parks, national wildlife refuges and public lands are to suffer the impacts of new energy corridors. “The Energy Department needs to seriously evaluate alternatives to minimize the number of corridors and maximize use of renewable energy, and it should include requirements to presumptively limit all projects to designated corridors,” she said. Culver added that the impacts will be significant. As proposed, corridors will threaten six national wildlife refuges, three national parks, seven national monuments and more than 60 current and proposed wilderness areas. “The Energy Department has this one chance to get these corridors right and to improve access to renewable energies, such as wind and solar,” said Culver. “With appropriate planning, they could address our transmission needs while also avoiding sensitive protected lands.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel