| ||

The making of an exhibition

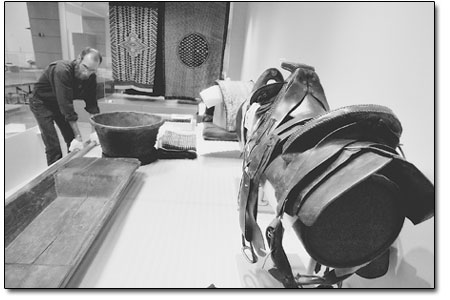

by Jules Masterjohn What goes on before the curtains rise or the gallery doors are flung wide is often a mystery to the viewer. Thankfully, there are professionals and their enormous level of detail that makes a viewer’s experience seamless. If you don’t notice that you are in a gallery but, rather, that you have been transported into a different world, you know that someone, probably many someones, have poured countless hours into creating that atmosphere, leaving no nuance unattended. For the last two months, this has been the case at the Center of Southwest Studies galleries at Fort Lewis College. In preparation for the current exhibition, “Old Spanish Trail,” staff and Oregon-based installation professional Jack Townes have been constructing light boxes, reconfiguring display cases and sorting through the center’s array of display mounts and materials. Recycling and reusing happens quite a bit here, and Townes offers, “The men and women in the college’s Physical Plant can do anything with tools and paint!” Townes was in town for about three weeks in December, leading the installation crew on the new exhibit. “Ramrod” is actually the word he uses to describe his role at work here. “The volume gets turned up when the Center knows that ‘the guy’ is coming,” he says. “They know its show time.” Townes adds that it usually takes a few days for the crew to get in sync with him, each other and the multifaceted tasks required to install an exhibit as complex as the “Old Spanish Trail.” With more than 100 artifacts related to 200-plus pages of documentation, the galleries are filled, neatly and elegantly, with objects, text panels and maps. Before he arrived, the center’s curator and interim director, Jeanne Brako, had designed the overall flow of the exhibition, basing her plan on the story, or script, written by volunteer Art Gomez. Her concept of a trail leads viewers over terrain and through time. The Old Spanish Trail was a Ute trail traveled by pack traders using burros and mules, between Santa Fe, N.M., and Los Angeles between 1829-48. According to the Old Spanish Trail Association, “It was a trail of commercial opportunity, Western adventure and a dose of mischief involving slave trading, horse thieving and raids. The Old Spanish Trail route was established along a loose network of Indian footpaths that crossed the Colorado Plateau and the Mohave Desert.” In 2002, the U.S. Congress designated the route as a National Historic Trail. When Townes and Brako get together, there is an intellectual giddiness in the air. They share an interest in and love for history and art, processes and details … many details. Their connection goes back to Queens, N.Y., where they were teammates in a gymnastic club. In high school, while Brako was working as an intern at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Townes got interested in the possibility of working in the museum world. “I’d go to see Jeanne, and she’d take me into Conservation where I would see a Rodin just sitting in the hall. I got excited when I met the metals conservator at the Met and thought how cool it would be to do this for a living.” Over the decades, the two have remained friends and colleagues and find themselves working together on a few major installations each year. Usually, Townes’ visits are timed with his other Southwestern mount and installation gig for the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe. When we met in December, he had just finished installing “Native American, Modern 1960 to Present” at the Wheelwright. He talked a bit about the contrast in working at the Wheelwright, a world-class museum with a budget to support its programs, and at the Center of Southwest Studies. “The Center of Southwest Studies is the crown jewel of Fort Lewis College and Durango,” he says. “They are putting together national level shows on a limited budget, installed by a crew of student workers and others at the beginning of their museum careers. What gets done here on a shoestring is amazing.” The center recently acquired a large vacuum mount press, given to them by another museum that was looking for a worthy home for the equipment. The room-sized apparatus is large enough to mount graphics or text onto a 4-foot-by-8-foot backing board. Museum professionals like Brako and Townes get excited about this kind of thing because it enables the center to present its information in a format used by the best museums in the country. This tool makes magic happen for an exhibition. For Townes, the right tools are integrally important to his profession. His 1,300-square-foot studio in Oregon is both a complete woodshop and a jeweler’s studio, equipped with torches, anvils and a full array of metalworking tools. For this exhibit, he crafted small, telescoping, brass wire mounts that will be used to hold and display tobacco bottles. The telescoping aspect is something he “borrowed” from another mount maker and which allows the mount to be used for the display of different-sized objects. The brass had to be coated with a substance so the metal wouldn’t stain the leather-wrapped bottles. Townes demonstrates how foam shapes are fabricated and used to hold saddles and then shares a few tricks about making the mount look almost invisible, yet the security mechanisms still accessible. With a pair of white cotton or latex gloves either on his hands or in his back pocket at all times, Townes gently picks up a 150-year-old leather pouch and describes its construction. He enthusiastically works the room, telling me the stories of various artifacts. “We have found things in our collection that we didn’t know related to the Old Spanish Trail,” Brako says. Through researching specific objects in the center’s collection, some interesting cultural connections have been discovered. One artifact, for example, is a Ute carrying case with a Euro-American fabric tassel. Some of the artifacts in the exhibition that relate to the Santa Fe leg of the Old Spanish Trail also are being loaned from the Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe. The institution is a partner in this exhibit and the show will eventually travel there. The research by contributors not on the center’s staff has informed this exhibit, allowing the center to “rotate its cultural focus.” For example, the center’s Hispanic oral history collection is lean, and this exhibit has brought more stories to the collection, which is very gratifying for Brako. “This exhibit has brought in a lot of cultures as part of the story.” • The “Old Spanish Trail” exhibit is on display at the Center of Southwest Studies on Sunday through Friday from 1- 4 p.m. and Thursdays until 7 p.m. An opening reception will be held Sun., Jan. 27, from 1-4 p.m.

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel