| ||

| Divided by wilderness Mountain bike community ‘sleighted’ by new wilderness proposal SideStory: The future of San Juan Public Lands

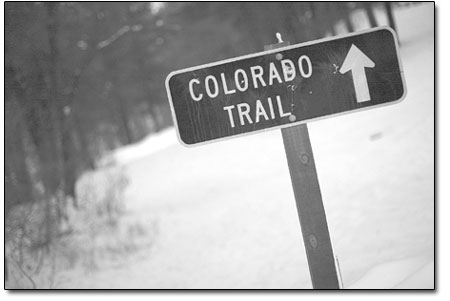

by Will Sands Fat tire recreation and wilderness preservation are at odds just outside Durango. A revision of the San Juan National Forest Plan was recently released and is now hitting the mountain biking community hard. The draft calls for the creation of a 50,000-acre West Hermosa Creek Wilderness Area, a move that would close 20 miles of the Colorado Trail and shut off at least six other trails to mountain biking. Since 2005, the San Juan Public Lands Center has worked to revise and reassess the guiding principles of the San Juan National Forest. That work came to fruition on Dec. 20, when the agency released its draft forest plan to the public. Thurman Wilson, assistant manager of the San Juan Public Lands Center, commented, “We started the process in 2005 with a lot of community meetings. We looked at small areas at a time and asked people to identify outstanding characteristics. We also asked people to tell us what things are working under the current management and what should change.” As part of any forest plan revision, roadless areas must be considered as potential wilderness areas. Wilderness designation provides exceptional protection but also limits mechanized travel, including mountain bike recreation, and that exclusion has long been a paradox for many mountain bikers. “Wilderness is open to most passive forms of recreation,” said Mary Monroe, executive director of Trails 2000. “I think mountain biking fits as a passive form. Unfortunately, when the Wilderness Bill was passed in 1964, mountain bikes hadn’t been invented.” Far and away, the largest roadless area in the San Juan National Forest surrounds Hermosa Creek, northwest of Durango. The 145,000-acre area is also among Durango’s most popular mountain biking resources and is home to the Hermosa Creek Trail and a large section of the Colorado Trail, both revered by mountain bikers. The roadless area contains more than a dozen other trails, which attract both mechanized and nonmechanized trail users. Nonetheless, the roadless area’s size and pristine quality made it the top candidate for wilderness designation, according to Wilson. “The Hermosa Roadless Area is our biggest, and of all our roadless areas, we felt it best met the characteristics of wilderness,” he said. “All along we’ve wanted to protect that wild character, while respecting the traditional uses.” In order to respect the tradition of mountain biking in the drainage, the Forest Service elected to leave the Hermosa Creek Trail and the trails to the west, like Jones Creek, Pinkerton-Flagstaff and Dutch Creek, largely as they are now. Looking at the “more primitive” east side of the roadless area, the agency’s preferred alternative recommends a 50,895-acre West Hermosa Creek Wilderness Area. The wilderness would run from Corral Draw at the north to the Clear Creek trail at the south and close access to mountain biking on 20 miles of the Colorado Trail and completely shut off the South Fork, Salt Creek, Grindstone and Sharkstooth trails to cyclists. “The reason we selected that area is that we didn’t feel like there was much use on that part of the roadless area,” Wilson said. “Plus, the Colorado Trail certainly goes through sections of wilderness elsewhere.” Bill Manning, director of the Colorado Trail Foundation and former head of Durango’s Trails 2000, begged to differ. His group has found that mountain bikers are actually one of the biggest users of the Indian Trail Ridge or Highline section of the Colorado Trail. Manning added that wilderness designation would dramatically alter what is now a multiple-use dynamic. Wilderness designation would also effectively eliminate the Molas Pass to Durango ride, a 75-plus-mile grunt considered one of the best epic rides in the nation. “It’s safe to say that the Colorado Trail Foundation will be taking a really careful look at the proposal with the knowledge that it would be a big change in the allowable use on a big segment of the trail,” he said. “We know a variety of users like that section. It’s definitely cherished by hikers, cyclists and horseback riders, and mountain bikers are probably the biggest users on that stretch.” Mark Ritchey, a concerned citizen and mountain bike advocate, has been involved in the Forest Service process since the community meetings in 2005. He recalled discussion of designating the west side of the drainage a “primitive area,” a move that would have provided near-wilderness protection while respecting traditional recreation uses. With this in mind, the wilderness recommendation caught him off guard. “It was my understanding from the original meetings that we were going to protect these areas with a different designation and respect the existing trail users,” he said. “Now we’re in danger of losing trails, and particularly the Colorado Trail, that are of high value to the community.” Like Monroe, Ritchey commented that wilderness presents a dilemma for conservation-minded cyclists. “It’s definitely a conundrum for mountain bikers,” he said. “We all love wilderness areas but feel like we’re excluded by their designation. It’s not a comfortable place to be in.” Monroe agreed that she had hoped the Forest Service would consider other alternatives and preservation tools rather than alienating one user group outright. “When you have an area that is already popular among a recreation group, to make an about-face change and recommend wilderness is going to create more conflicts than solutions,” she said. “There are alternatives and options that offer this type of preservation and protection but still take trail users into consideration.” Wilson concluded that the wilderness recommendation is not necessarily written in stone. The Forest Service has kicked off a scoping period and will conduct public meetings in coming weeks. In addition, the Forest Service can only recommend wilderness designation but the U.S. Congress has the final say. “Congress is the only body that can designate wilderness,” he said. “We’re making a recommendation, but it would take a congressional action to make it happen. In the meantime, we’d be managing it to maintain those wilderness characteristics.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel