| ||||

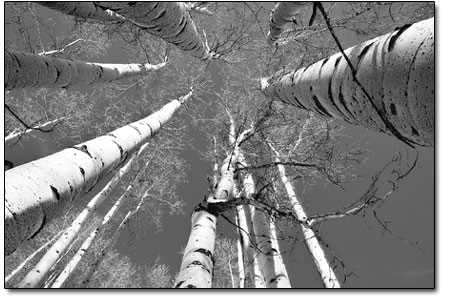

| The decline of the aspen Community looks for answers to mysterious aspen tree die-off SideStory: Getting a grip on Sudden Aspen Decline

by Will Sands Colorado’s leaves are changing in a way that is causing serious concern. “Sudden Aspen Decline,” a still relatively unexplained phenomenon, is striking and killing large stands of aspen trees all over the state. The decline has hit Southwest Colorado especially hard, and land managers, activists and community members will search for solutions next week. A community workshop on the growing problem is set for Durango on Tues., Feb. 19. SAD came into its own last fall, when visitors to Colorado’s forests started noticing fewer yellow aspen displays. In their place, leaf lookers found more and more stands of dead and dying aspen. Since its recent origin, SAD has grown exponentially in size and severity, threatening current and future aspen forests as well as wildlife habitat and viewsheds. Sudden Aspen Decline was first noted by land managers on the San Juan National Forest in 2006. At that time, an aerial flyover found that nearly 17,000 acres had been afflicted by the phenomenon. Last summer, the Forest Service conducted a second flyover, discovering that the number of dead and dying stands had more than doubled to a total of nearly 40,000 affected acres. With only 300,000 total acres of aspen stands on the San Juan National Forest, local land managers are definitely concerned. “Sudden Aspen Decline is happening very rapidly. That’s part of what’s so alarming,” said Dave Dallison, timber program leader for the San Juan National Forest. Last summer, SAD started showing up elsewhere in the state as well. The Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison National Forests saw their aspen forests go into deep decline and experienced massive die-off virtually overnight. Northern Colorado is also taking the hit, with aspen groves near Craig in some of the worst shape of all. The cause of Sudden Aspen Decline remains somewhat mysterious. Researchers believe that widespread and severe drought conditions earlier this decade caused stress in the trees. That stress weakened mature and low-elevation stands of aspen in particular, making them more susceptible to infection and infestation. “Once we noticed the problem, we had the researchers down early on,” Dallison explained. “They found a host of things going on with the trees, ranging from pathogens and defoliants to bark beetles.” Ryan Demmy Bidwell is executive director of Colorado Wild and one of the presenters at the Feb. 19 workshop. Drought also seems to be the most logical SAD suspect for Bidwell. “I think we’re still learning what’s going on out there,” Bidwell said. “What I’ve been able to gather is that the drought and warm temperatures of the last 10 years have taken a serious toll on our aspen. No one really seems to know the extent of the problem or if there’s much we can do about it.” Researches have reported that weakness in the trees is giving aspen borers, bark beetles, canker and other ailments an added advantage. However, unlike past cases of aspen mortality, SAD appears to be hitting stands harder by striking at the roots, or clones, which prevents future regeneration.

“We normally see a lot of mortality in aspen because it is a short-lived species,” Dallison said. “But we’ve never seen it concentrated like this. We’re also seeing a lot of root stock dying, and that stock is being replaced by other species. When you have trees like ponderosa pine and scrub oak taking over, it leads to a much more flammable landscape.” No one really knows how to turn back Sudden Aspen Decline, according to Dallison and Bidwell. There is hope that next week’s Durango conference will bring the San Juan National Forest and Colorado a few steps closer to an answer. “That’s the point of the workshop,” Dallison said. “We’re trying to get a bunch of folks together and look for answers.” Bidwell added, “I really applaud the San Juan National Forest for continuing to have an open conversation with the community about the future of our aspen. This conference is really going to ask, ‘What should we be doing about aspen management?’” One early conclusion that activists and land managers have reached is that aspen need adverse conditions to thrive. Over time, disturbance leads to regeneration of aspen and has ultimately created the healthiest stands of the trees. “Everybody agrees that we want to keep aspen on the landscape,” Bidwell said. “Everybody also recognizes that aspen need disturbance to be successful. Historically, that disturbance has come in the form of fire.” New aspen shoots in areas like Missionary Ridge are showing strong resistance to Sudden Aspen Decline, according to Dallison. This fact makes a strong argument for the use of prescribed burning and timber harvest as management tools. “The younger stands that have been regenerated either by harvest or fire seem to be holding their own,” Dallison said. “I think the real question is going to be how far gone can an aspen stand be and still regenerate.” More than two-thirds of the San Juan National Forest’s aspen groves are located inside roadless areas and designated wilderness, making fire the only viable management tool. However, timber harvest is an option elsewhere and has even won an unlikely champion in the form of Colorado Wild. “Colorado Wild advocates using fire to restore disturbance to the landscape,” Bidwell said. “At the same time, I think there can be a role for small-scale timber harvest in managing aspen and providing local jobs. But I also think Sudden Aspen Decline raises a lot of questions about how that harvest should be done.” Heading into next week’s conference, there are a lot of questions about what Sudden Aspen Decline will bring for the future of the Four Corners and Colorado. So far, the phenomenon has been confined to lower elevations and more mature trees and is still relatively manageable. “If those lower, older trees are all we lose, Sudden Aspen Decline is probably not going to be a major issue,” Bidwell said. “But if we start to see SAD moving up into higher elevations and wetter stands, we could have a crisis on our hands.”

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel