| ||

A tale of two utilities

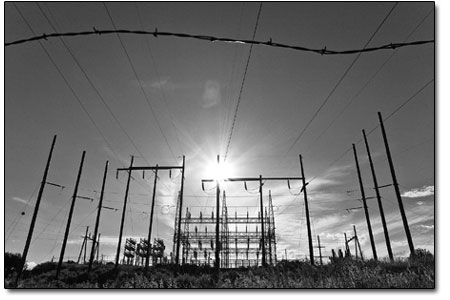

by Allen Best Officially, at least, Xcel Energy was nowhere to be seen at a recent hearing at the Colorado Public Utilities headquarters in Denver. But Xcel, the investor-owned utility that serves much of urban Colorado, was like an elephant in the room, in what was described as a precedent-setting “conversation” between PUC commissioners and Tri-State Generation and Transmission, the dominant supplier for rural Colorado, including La Plata County. At every turn, Tri-State emphasized differences with Xcel: Tri-State customers have generally lower incomes. Their market share is much smaller. It’s more difficult to integrate renewable energy because of a different daily demand curve, which has fewer mid-day spikes. Particularly prickly were the questions of Matt Baker, a PUC commissioner appointed by Gov. Bill Ritter in January. Does it bother Tri-State, he wanted to know, that Xcel has already developed some of the best wind resources in rural Colorado – on Tri-State turf? No, responded Ken Reif, a senior vice president and general counsel at Tri-State, because Tri-State has different needs than Xcel. “At the moment we do not view wind as a viable baseload resource,” he said, referring to the constant, or base demand. Again and again, Tri-State insisted that cost is the driving force for determining how electricity is produced. Coal, at the moment, remains the cheapest. Even that did not go unchallenged. Baker questioned whether coal prices will remain low, given recent increases. The exchange was the first chapter in what could become a loud debate in Colorado as Tri-State seeks to build a major new transmission line and power plant, which Tri-State representatives say is necessary to meet future needs. Tri-State projects a 189-megawatt shortage in supply by 2014. However, Tri-State clearly will need a permit from the PUC if it builds a power plant, but it disputes the PUC’s authority to demand information about its major transmission lines. Tri-State representatives emphasized that the meeting was not a “hearing,” as is mandatory of Xcel, but rather a voluntary report. By whatever name, it was part of a broader effort by the Ritter administration to reduce the state’s carbon footprint, PUC Chairman Ron Binz said in an interview later. “I think all sectors of this industry need to pull their share,” said Binz. “Everybody has a role to play in this, including the co-ops.” A central issue is to what extent coal can be a bridge into the future. Tri-State is conceding carbon constraints but is holding out hope for technological development. A key question is whether CO2 can be filtered from power plants and sequestered underground. An experiment recently launched New Mexico’s San Juan Basin, south of Durango, is part of that effort. Some 75 percent of Tri-State’s electricity in Colorado comes from coal, compared to 64 percent for Xcel. Tri-State owns part of a coal mine in Craig and even has railroad cars for hauling it. Xcel, in contrast, has invested more heavily in natural gas, which is more expensive than coal but has half the carbon footprint and can produce electricity more readily during peak demand. Natural gas also allows Excel to more readily integrate renewables. Xcel believes it can meet 30 percent of its demand through renewables. Environmental groups – and to a great extent, Colorado’s government – wants to see a much more rapid development of renewable energy sources and a greater emphasis on energy efficiency. Guiding the effort is the Colorado Climate Action Plan, which ambitiously calls for a 20 percent reduction in greenhouse gases by the year 2020 and an 80 percent reduction by mid-century. 4 Different roots The differences between Tri-State and Xcel stem from the companies’ origins. Public Service Co., Xcel’s subsidiary in Colorado, has roots extending to 1869, when business leaders in Denver formed a company to provide gas lighting. In time, the company expanded to deliver electricity. Cities, with their closely spaced customers, were easily serviced. As such, they provided greater profit to private, monopolistic entrepreneurs. Extending power lines to farms and ranches, however, was far more expensive. In the 1930s, most of rural American remained without electricity. To dismantle this electrical divide, Congress in 1935 set up the Rural Electrification Administration to help fund new electrical co-ops. Unlike Xcel, which is owned by investors and traded on Wall Street, these electrical co-ops are owned by the customers. Each customer is a shareholder, with a right to select directors. Several co-ops combined in 1952 to create Tri-State, tasking it with the job of generating electricity. Much of that electricity then came from dams, but today only 15 percent comes from hydroelectricity. The growth in demand has been met primarily by coal and, increasingly, natural gas. Today, Xcel delivers 64 percent of electricity consumed in Colorado, either directly to consumers or to sale of rural co-ops and municipalities. Tri-State delivers 14 percent. Municipal utilities deliver most of the rest. Despite its roots in representative democracy, Tri-State is guarded. Board meetings are closed to the public except in rare instances, and dissent is not welcome, say critics. Xcel has resisted change, too, but less stubbornly. For example, after finally reaching a compromise with environmental groups, it is now building a 600-megawatt power plant near Pueblo but plans to decommission two smaller coal-fired plants in exchange, one in Denver and the other near Grand Junction. It has also increased efforts for what is called demand-side management, improving energy efficiency such as encouraging the use of compact-fluorescent lightbulbs and conservation, such as in programs that temporarily cut use of air conditioners on hot summer afternoons. Tri-State has been less aggressive, particularly about developing renewables. It is planning to participate in a solar plant in New Mexico, from which it will get 10 megawatts. This year, it is also calling for development proposals for wind and solar for 50 to 100 megawatts. Use of renewables might be expedited, said Tri-State’s senior vice president for external affairs Robert “Mac” McLennan, if means to store compressed air can be found in Tri-State’s service area. Such storage is considered critical for using solar and wind to supply electricity for baseload demand. However, in meeting its impending shortfall, Tri-State’s Plan A was to partner with a Kansas company to build two coal-fired power plants at Holcomb, Kan., in the state’s southwest corner. But Gov. Kathleen Sebelius last October denied air-quality permits for the plants, citing carbon dioxide emissions. Tri-State is appealing the veto while readying Plan B: either a coal-fired power plant or a nuclear generator, this time in Colorado, near Holly. The land and water rights have been secured, officials said, and air quality studies are under way. At least officially, Tri-State accepts that CO2 emissions taxes, estimated at $50 per ton, will make coal-fired electricity more expensive. As such, Tri-State is now looking “very hard” at nuclear, said McLennan. Still, coal is Tri-State’s first choice. Environmental groups – and a federal laboratory – see this as a dangerous gamble. The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California issued a study in March that found Tri-State had the most carbon-intense resource plan of 16 utilities in the West included in the study. The research repeatedly faulted Tri-State for poorly incorporating the risk of carbon into its decision-making process. Instead of expanding supply, several PUC members asked, can Tri-State instead figure out ways to reduce demand? Binz, the PUC chairman, suggested that Tri-State could engage a third-party energy efficiency firm, such as was done in Vermont, Wisconsin, and several other states. Improving efficiency costs less than adding new supply, he said, although it can be a tough sell to consumers. Tri-State argues that, in the short term, demand can’t be dented sufficiently –it needs a new power plant. It further argues that it does not have the relationship with consumers to facilitate energy efficiency. That Tri-State is changing, there is no doubt. The executive team has largely been replaced in the last four years. Moreover, there has been dissent from the coal-first approach even in the most conservative rural communities. But whether the rate of change will be fast enough remains to be seen. “We are not as far along as Public Service (i.e. Xcel) in our process,” noted Reif, Tri-State’s lawyer, near the end of the recent meeting, “but our pace is far greater than it was even two years ago.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel