| ||

Extra special beer

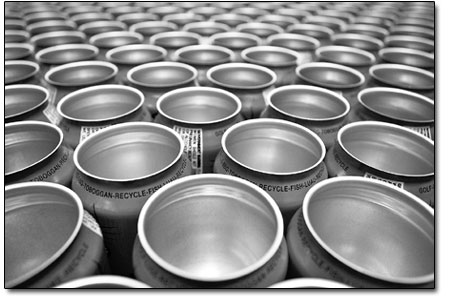

by Jeremy Kirby It’s hard to write about the extra special bitter without comparing or contrasting it against its fraternal brother, the pale ale. Both have nearly the same lineage and ingredients, and both appeared around the same time. In fact, for a while the two names were interchangeable for the same base beverage; It was called a pale ale if it came from a bottle, and a bitter if it was from draught or cask. Ultimately, in the U.S. at least, the styles split and became two different beverages with different characteristics, with the bitter family being broken down into another three subcategories: the common bitter; the special or best bitter; and the grand daddy of them all, the extra special bitter. The extra special bitter, or E.S.B., is a copper-colored, heavily hopped, often full-bodied and malty beer. It generally has an alcohol level of 4.8 percent and above and is sometimes served with less carbonation than other beers of its strength. It usually has a toasted aroma with a bit of fruitiness from the yeast. Although it may be a bit hoppier than a pale ale, the hops are more apparent in the taste than in the aroma. The story of the bitter and the pale ale are closely intertwined with the history of the industrial revolution of England during the 18th and 19th century. Making the malted barley for the beer was an inexact and difficult process, done above a wood fire, on slotted wood floors. This gave nearly all malt a dark color and a woodsy/smoky aroma and taste. This, in turn, gave almost all the beers made from the malt similar qualities. The Industrial Revolution, however, brought with it two things important to the emergence of the pale malt that would eventually lead to the E.S.B. The first was coke, a smokeless byproduct of raw coal, which was used as a substitute for wood in drying the malt. Secondly, steel became more widely available and was being used in the construction of the malting kilns. The better heat source and better kilns made malting a more controllable activity allowing for the easier production of a light or pale malt. As a result, the new pale malt was more plentiful and cheaper than ever. The bitter made its official debut some time between 1702 and 1714, but remained mostly a drink of the upper class. The real dawn of the bitter and other pale ales had to wait another 150 years until glass became affordable. Finally the drinking class could afford clear glass drinking vessels. Before this, beverages were mainly available to commoners in earthenware jugs and drunk from containers made from wood, stone, clay, leather, metal or almost anything that would hold the suds. At its high point, the bitter was considered by many to be the national drink of England, but unfortunately its popularity and ubiquitousness is finally waning with England’s younger folk turning to imported continental or American lagers, and brightly colored mixed drinks. It definitely is the end of an era. Fortunately, the E.S.B has had a rebirth in North America. Craft brewers in the states have made it a hobby of finding dead or dying beer styles from around the world and reviving them. The website www.beeradvocate.com lists more than 650 beers that fall into the E.S.B. category, with the bulk of them being made in American breweries or brewpubs. That is good news for brewers and drinkers alike. It is a great beer, worthy of its longevity. As for what to eat, match an E.S.B up with some flavorful fish, grilled or even smoked. Actually go straight for the trump card and order up some fine fish and chips. They go great with this extra special beer. Going to a cheese party, E.S.B. goes best with buttery cheese, like brie or havarti. If your E.S.B is on the heavier end of the scale, grill up some wild game or pork. The caramel flavors in the beer match up perfectly with caramelized glaze and seared edges of the meat. If you’re in the mood to try an E.S.B, Ska’s famous E.S.B is readily available about town in sixpacks of 12 oz cans. The beauty of cans is you can take the beer places you normally wouldn’t want to take bottles: camping, boating, peak bagging. For other commercial examples, check out Fuller’s E.S.B. (5.9 percent ABV), an import from England or Redhook’s E.S.B (5.77 percent ABV). For more regional examples, get your hands on Sawtooth Ale (4.75 percent ABV) from Left Hand Brewing Co. in Longmont or 14’ER E.S.B. (5.13 percent ABV) by Avery Brewing from Boulder. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel