|

| ||||

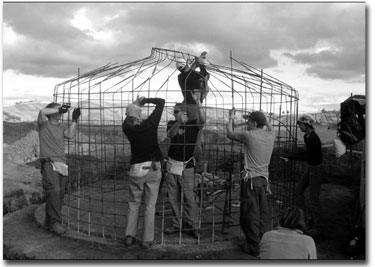

| Breaking down borders

by Amy Donahue Mixing concrete, bending rebar and tying wire may not be typical preparations one makes before a vacation. But then again, this is no ordinary trip. The construction work is just a short introduction to the type of work that will be done this summer when Fort Lewis College’s Engineers Without Borders (EWB-FLC) program travels to remote villages in Laos and Ecuador. Nearly 20 Fort Lewis College students, several community supporters and professors Don May and Laurie Williams spent last Sunday learning how to lay masonry and build ferro-cement tanks. The knowledge will be used to help install sustainable water systems in the developing communities. The FLC group is a local chapter of a national organization that partners with developing communities to improve their quality of life. Through the implementation of environmentally sustainable, equitable and economical engineering projects, the organization tries to promote the development of globally aware individuals, said Laurie Williams, assistant professor of physics and engineering at FLC. The FLC chapter was started in the spring of 2004 by Don May, professor of physics and engineering. Williams joined the club as co-director the next year. “All of my adult life, I have been looking for an opportunity to combine my professional career with humanitarian service without compromising my commitment to my teaching or my family,” May said. “This has been the answer. EWB has become an integral part of my teaching, and my family has become a part of EWB.” EWB-FLC is a completely volunteer organization. Over the course of the academic year, students and community members work together with May and Williams to develop and design projects and raise funds for both the equipment and travel expenses. Since the club’s creation, EWB-FLC has worked on several projects in Thailand and Ecuador, and this summer will begin a project in Laos. The Hmong village of Ban Phakeo, Laos, is being developed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In May, EWB-FLC will develop a clean water and pipeline system to replace the village’s meager current water source. In July and August, a larger group will return to the Chimborazo region of Ecuador to develop community water systems in two villages. At both projects, EWB-FLC members will conduct health assessments, test water quality and collect map data, as well as provide basic community health and sanitation education, Williams said. Megan Schooley, junior anthropology student, cited EWB-FLC’s commitment to sustainability and sensitivity to a range of issues as vital to her involvement. “I was hesitant at first because I had this idea that EWB was a patriarchal program that went into communities in the developing world and told them that they needed to develop in order to become ‘modern’ and ‘successful,’” she said. “I instantly realized the value of EWB as an organization that acts upon requests made by communities in the developing world who seek to improve their quality of life through the implementation of water and sanitation systems.” The club is focused on discovering the appropriate technology for each community as well as looking at social, environmental and political factors that may affect the project, she said. “All of these projects are requested,” said Rachel Ballantyne, a junior engineering and agricultural student. “We don’t go somewhere and say, ‘What you’re doing is wrong, here’s the right way.’” May said that sustainability is the hardest aspect of project planning for EWB. He added that the most important part of ensuring sustainability is following up on communities, as well as committing to more than one year in the same village. “Sustainability is a long term process,” he said. “We won’t know for years if we have been successful.”

Community building is another aspiration of the club. EWB has grown to include a number of community partners as well as many students from varying disciplines. This year, more than 80 students have attended meetings, and of the 40 active members, 34 will be traveling to villages in Ecuador and Laos to implement water and sanitation systems. The students come from various departments, ranging from engineering to English, psychology, chemistry and sociology. Ryne Waggoner, president of the club and a junior mechanical engineering student, said that in the last two years he has seen EWB-FLC’s membership grow dramatically, giving the club the ability to complete more and larger projects. “I think this growth is due to students realizing that EWB offers a holistic approach to learning for all majors while still helping communities around the world,” he said. The unique thing about EWB is that members are not only affecting the communities they work in, but also the global awareness of critical problems, said Brian Campbell, a local civil engineer with Bechtold Engineering. Campbell started working with EWB-FLC in 2004 as a student and now continues to participate as a community member. He said one of his hopes for the club is to provide a forum for creating a sense of global awareness and responsibility in students and community members alike. “We have things so easy, and our problems are so small as compared with the rest of the world. We can do so much with that advantage,” he said. EWB provides a type of learning that is congruent with the liberal arts education model, said John Byrd, a community supporter. “It teaches students about cultural sensitivity, the conditions of other people and the skills to make a difference,” he said. “Obviously it helps the recipient communities get better water as well. In doing so, EWB respects cultural differences.” This cultural sensitivity is most readily apparent in the implementation trips. Because members are traveling to remote villages in developing countries, the experience is far different than a tourist vacation. “I enjoy the community service part of EWB, and I would much rather go complete a project before touring the area,” Ballantyne said. “You truly understand and connect with the people when you are involved.” Implementation trips provide the grassroots type of involvement that Campbell said is important for creating a sense of global responsibility. Because students have the opportunity to interact with everyday people in different countries and cultures, they begin to feel a connection with that community. “Going on an implementation trip is perhaps the most rewarding thing in my life,” said Rachel Schur, junior engineering student. “It is also one in which I grow and learn so many invaluable lessons, ideas and thoughts.”

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel