|

| ||||

| Sightseeing in Purgatory

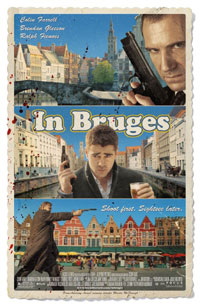

by Judith Reynolds Modern travel and old-fashioned Purgatory have one thing in common – waiting. Whether a delayed flight or the Last Judgment on your soul’s destination, waiting can be excruciating. Irish playwright Martin McDonagh’s first feature film, “In Bruges,” is all about the excruciating wages of sin and waiting. Now playing at the Abbey Theatre, “Bruges” extends McDonagh’s dark landscape in a brilliant film journey not unlike his troubling plays. Known as the bad boy of Dublin, McDonagh turned 38 only last week. He always seems to have something new to say about old human conundrums. All of McDonagh’s works are fraught with evil and human stupidity – deadly consequences resulting from foolish decisions and incomprehensible actions. As in his plays, “The Leenane” and “Aran Islands Trilogies,” and a recent production of “The Pillowman” on Broadway, McDonagh updates the wages of sin by bringing a rich Catholic conscience to bear on an odd hybrid – crime comedy. If you haven’t seen any of McDonagh’s plays, be prepared for unrelenting bad decisions, horrendous acts, colossal guilt and stupefying remorse. And then there is McDonagh’s off-the-wall notion of grace. As bad as things get in any McDonagh work, redemption is not impossible. Frequently, it arrives very late and in unexpected ways. The plot for “In Bruges” is simple enough. Two Irish hit men have fled London after a job gone wrong. Well more than 30 minutes into the film, we learn about that event through flashbacks. We never learn why Ray (Colin Farrell) shot a priest and accidentally killed a small boy waiting for confession. That’s one plot detail you have to let go. Ray and his more seasoned partner Ken (Brendon Gleeson) are mere underlings in a crime family. Their boss, Harry (Ralph Fiennes), stays in touch via telephone, and he finally shows up toward the end for a harrowing conclusion. Harry ordered Ken and Ray to Bruges for two weeks, until things cool down. In Bruges, Ken knows how to handle the boredom of waiting. He plunges into sightseeing in what is repeatedly referred to as a “fairy-tale city,” an almost perfectly preserved Medieval dreamscape. Only later do you realize that the ambiguity of the killers’ fate in this odd place is a stand-in for Purgatory. The two men are a kind of young Dante in trouble, traveling with a father-like Virgil. Visits to several of Bruges’s spectacular museums, churches and crypts make that parallel clear as Ken tries to interest Ray in an abundance of late Medieval art and architecture. The camera pores over scenes of flayed saints, skeletons arranged on dungeon altars and one particular painting by the Gothic genius Hieronymus Bosch. A boyish and reluctant Ray finally surrenders to Ken’s sightseeing plans in order to experience a little freedom. They stumble on a film crew in the midst of town where Ray spots and pursues a pretty blond, Chloë (Clémence Poésy). The pick-up scene demonstrates McDonagh’s flair for comedic writing, especially with Ray’s opener. Farrell and Poésy then bring a lightness and charm to odd bits of dialogue which link up with plot elements. Ray’s attempt to hook up with Chloë also provides a perfect subplot. It leads to another set of interlocking characters, Chloë’s world and the colorful misfits of the film cast and crew. Not to push the Boschian metaphor too far, but McDonagh includes a dwarf in the person of Jimmy, an American actor (Jordan Prentice). The film is a kind of dream or play-within-a-play, which deepens McDonagh’s descent into Hell even further. Later, when you see the crew on a night shoot in medieval costume, the Hell-Purgatory connection becomes visually undeniable. The story is so full of unexpected surprises, no more will be given away here. Suffice it to say that Ray and Ken encounter a spectacular array of characters: Erik (Jéremé Renier) is a local thug; a bureaucratic ticket taker (Rudy Blomme) figures twice in comic scenes at the famous Bruges Tower; and even mythology’s Three Graces make an appearance at the Tower – three overweight American tourists who challenge Ray’s insult and enter into a royal public scrap. The casting and performances support the whole enterprise. I’m generally not a fan of Farrell, but he’s as natural as Irish oatmeal in the role of the young and confused Ray. Gleeson’s fatherly Ken registers warmth, patience, understanding and sacrifice. Fiennes’ volatile Harry crackles with menace and surprising principle. Another subtext is the code by which these men of dishonor live. For those who know McDonagh’s plays, his penchant for seemingly innocuous dialogue and silly word play may intrude. But there’s a point in McDonagh’s banalities. Like the American playwright David Mamet, to whom McDonagh has been compared, the Irishman has an ear for nonsense in human conversation, especially the midst of grave situations. Fussing over words like “alcoves” or “nooks and crannies” in the midst of a murderous plan, makes for black comedy. And McDonagh is a master. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel