|

| ||

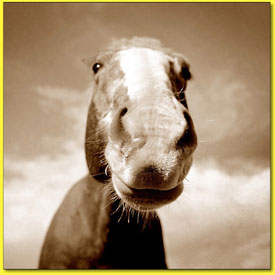

| Horsin’ around

by Jules Masterjohn Even before I moved to the West, I was well aware of the fascination that girls – especially young girls – have with horses. Though I was never drawn to horse play as a child, my friends had plastic horses that their Barbie dolls rode, galloping around their bedroom floors amidst small piles of diminutive stiletto heeled shoes, organza gowns, and fake fur shawls. I preferred the hairdresser’s chair and beauty salon set over saddle blankets and barns: my Barbie play involved fixing each doll’s hairdo after the long “ride” on the hard back of Flicka or Beauty. All seemed right in the world. When I was introduced to astrology as a preteen, it was dismaying to find out that, as a Sagittarian, I was supposed to LOVE horses. The truth was that I had not paid much attention to them. Learning that the animal’s nature was associated with power and freedom attracted my interest. Curious, I made efforts to cozy up to those great beasts by spending a few weeks one summer on the farm of a childhood friend. My secret goal was to get comfortable riding the horses. “Sandy,” a reddish-brown quarter horse, and I were getting to know each other, spending an hour or so each day together in the fields, forests and along the dirt roads that bordered the farmstead. One day, my chosen steed threw me while I mounted her in the corral. I landed in 6 inches of horse manure and wet dirt, terrified, as the mare hovered directly over me. It was more than 30 years before I considered mounting another horse, finally wanting and willing to let go of my fear of the mighty equine. Things went better on that ride, feeling “at one” with the spirit of the horse, understanding more about horse nature and much more about my own. Last week at the Open Shutter Gallery, I was offered another opportunity, through many photographers’ eyes, to deepen my appreciation for the essence of horse. A great portrait reveals the inner life of the sitter, and there are some superb portraits of horses in the current exhibit, “Spirit of the West.” As I entered the gallery, the steely stare of the wild stallion in Claude Steelman’s portrait “Untamed Spirit” confronted me. Eye to eye, the wildness and freedom in that being reached out to call forth those aspects within myself. Riveted, I remembered Sandy staring me down as my body cowered in the mud, those many years ago. A bit disturbed and also relieved to have the unresolved trauma jolted to my consciousness, I moved on to a more comforting image along the wall. The classic cowboy portrait “Wahoo Bill,” by Adam Jahiel, offered itself easily. Confidently, the cowboy sits atop his horse, whose head and tail cannot be seen: the photographer has cropped the image, suggesting that the horse’s massive body is the landscape upon which the cowboy rides. This representation of the horse as a foundational feature in the landscape is an honoring of the important role played by the horse, and horsemen and women, in the development of the West. In “Horse Shadows,” a cluster of six horses stand gathered at a fence line, apparently telling secrets as the sun sets behind them, their 24 legs each casting long shadows that stretch toward the viewer. Jahiel’s timeless photographs capture the mystique of the cowboy culture, which may be all that remains of the lifestyle as the 21st century progresses and open lands become more clustered with civilization. With his image “Cowboy,” Jahiel seems to portend this possibility: a folding chair with “cowboy” scribbled on the back sits alone and empty facing a group of tents in the distance. Tony Stromberg made me chuckle with his image “Unexpected Visitor.” The black-and-white photograph is strikingly composed and pictures a horse’s head peaking around the side of a trailer, looking straight at the photographer. Who, the image seems to be asking, isn’t expecting whom? My favorite horse portrait is not only framed and hanging on the gallery wall, it also is nestled in the large display bin that holds numerous other images by the photographers that the gallery represents. “Nosey,” by Shane Knight, is so disarming that I had to fall in love with the beast right then and there. The composure of the horse’s face, with its nose stuck right into the camera’s lens, is simply endearing. The sienna-tone of the image adds to its sense of charm. The ’60s television show “Mister Ed” comes to mind, and I almost expected the horse to animate, saying “Hey Wilbur!” Today, “Nosey” hangs on my office wall, reminding me that, although Sandy stood her ground above me many years ago, that was then and this is NOW. The best art opens doors to new and meaningful perspectives, offering us insights and accessibility into aspects of ourselves and of the world around us. • “Spirit of the West” is on display through Oct. 31 at Open Shutter Gallery. Located at 755 E. Second Ave. Gallery hours are 10 a.m. – 6 p.m., Monday-Saturday.

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel