| ||||

The power of words

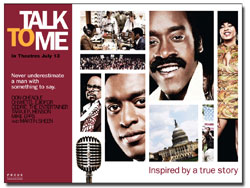

by Judith Reynolds If you want to see what passion looks like, see “Talk to Me.” The new biopic about Ralph Waldo “Petey” Greene (played with energy and fire by Don Cheadle) opened last week at the Abbey Theatre. Greene may have been a minor figure on the big American stage that encompassed the Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam War, but his importance as a player on a regional level cannot be questioned. As a radio talk-show host in the 1960s, he was credited with quelling further violence after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. On his wildly popular Washington, D.C., radio show, Greene talked down the rage that flamed the capital on April 4, 1968. Talk was Greene’s medium, and his story is worth telling. The film essentially is a biopic, yet it focuses only on the last 20 years of Greene’s life. He died of cancer in 1984 at age 53. “Talk to Me” is also the story of a friendship, a curious bond between two extremely different men. Greene was a volatile, larger-than-life ex-con who found a career in radio and then stand-up comedy. Dewey Hughes (Chiwetel Ejiofor) was an aspiring, by-the-book underling at a Washington, D.C., radio station. By all appearances, Hughes – who is still alive, has won 10 Emmys and lives in Los Angeles – was a middle class businessman intent on ascending the ladder of media management. Director Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) begins Greene’s tale in 1966 – in a prison setting. Fill in the blanks on a back-story, we really don’t need it. What Lemmons immediately gives us is Greene in full manhood – smart, confident, willing to speak truth to power. Enter Dewey Hughes. Visiting his brother who is incarcerated, Hughes spots the flamboyant Greene. The two men are a study in contrasts. Fearless, open to what life brings and ready for any encounter, Greene is a man of the moment. Hughes is cautious, judgmental and dismissive. How this relationship shifts and alters becomes the subtext in this film portrait of Greene. During his in-house radio show at the Lorton Correctional Facility, Greene recognizes and riffs on such euphemisms as the name of the institution itself. His “job” is part of a work program, and through it he discovers the power of his natural talent for talk. Mind you, this is before the era of political correctness. Greene is spontaneous, candid and often outrageous. His prison radio show becomes wildly popular precisely because the inmates believe Greene tells it like it is. Talk, or “interpersonal communication” as today’s educators would have it, is Greene’s gold. He’s the alchemist who turns the leaden realities of racism and injustice into the shining metal of truth. When the warden thinks shooting a desperate inmate is the best solution to a yard disturbance, Greene arrives just in time. Instinctually, he grasps the situation and talks the inmate down. The anecdote may be apocryphal, but Greene understands a man in crisis when he sees one. And Greene knows how to use words to calm a drastic situation. Via a whispered negotiation, the prison yard episode shortens Greene’s sentence and creates a template for future crises. On the outside, Greene uses his twin strengths, persistence and the gift of gab, to get a job in legit talk radio – at Hughes’s station, KWOL. At this point, the subtext goes into overdrive. Although initially skeptical, Hughes sees Greene’s talents and how the street-smart ex-con might pull his station out of a slump. As they become business partners and ultimately friends, not only does the story take on even more tension and energy, the changing dynamics illuminate a chapter in the lives of African-American men. Challenge or assimilate? Brilliant, even funny scenes at the station alternate with quiet conversations. And late in the film we learn important things about Hughes childhood that explain his decision to assume middle class dress, manners and language to get through a door. A variety of other characters populate the film, most notably Greene’s extraordinary girlfriend Vernell (Taraji P. Henson) She’s a creation worthy of the ancient Greeks. An angry goddess, Vernell won’t take crap from anyone, including Greene, whether he’s up or down on his luck. A perfect foil for a protagonist who is a verbal Hercules himself, Vernell is smart, strong, savvy and loyal. And she has her way of getting even. A hilarious scene with DJ Nighthawk (Cedric the Entertainer) will prove the point. Since KWOL is an R&B station, the soundtrack brims with great music. A pivotal tune, Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Going to Come,” is casually mentioned early in the film. At a key moment toward the end, the music appears and underscores Greene’s journey, linking it beautifully with the national mood. As “Talk to Me” lingers in the mind, one of the byproducts is wondering where all the fire went – not just Greene’s. The fire in the nation’s belly. In “Talk to Me,” the energy that fueled American blacks marching for civil rights is made vivid. The fervor that pushed young and old Americans to march en masse to end the bloodbath in Vietnam is also apparent. That’s the background for Greene’s unusual emergence as a simple, but not humble radio disc jockey in 1966. What happened to us? •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel