| ||||||

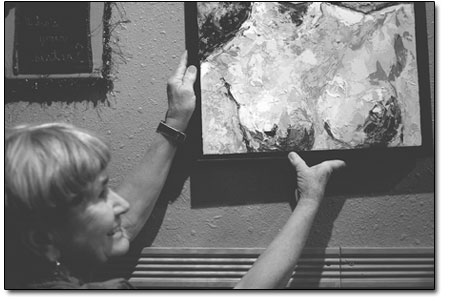

Hanging ‘Boobs and Bras’

by Jules Masterjohn I noticed the young man behind the counter looking my way. For one brief moment, I forgot that I was old enough to be his mother, then realized that it must have been the photograph of the perky breasts I was holding that caught his eye. Or maybe it was the sculptural rendition of a female torso wearing a magenta-colored bustier that compelled his gaze. Curious, I asked him what he thought about the artwork that I was hanging on the coffeehouse walls. With a shy smile, he told me that he’d have “no problem” looking at the art for the next two weeks. I doubt that the playful watercolor of the pastel bras was the reason for his focused attention … female body parts seem much more compelling to a person of male genetic coding. This was reinforced to me when one fellow stopped by to comment that he really liked the painting of the pink bra that I had just hung on the wall, and that he’d like it even better if he had just removed it from some lovely “babe.” Breasts and the garments that cradle them certainly do have varying associations. Early in life, my grandmother taught me about propriety as it applies to female undergarments. When I visited her during the summers, one of my favorite activities (and most cherished memories) was helping her hang out the laundry. My grandmother’s house was on a busy corner, if there was such a thing in a rural town of 700 people, and her clothesline was in plain view of the street. To keep her private matters private, my Grandma Min would first hang the sheets on the two outermost lines, effectively shielding the inner lines from curious eyes. I loved this time with my grandma, hiding between the long damp sheets, sharing time the way women have throughout the ages. For my grandma, the bedclothes were not enough protection from small town inquisition, so she hung the towels and rugs next, then the pants and shirts, and finally, the center lines were reserved for panties, slips, undershirts and brassieres. Here, her most personal, intimate garments were now fortressed from anyone whose eyes were not meant to see them. As a modern woman, I did not share my grandmother’s modesty, though I have always appreciated her use of metaphor with the laundry line. By contrast, a few years later at a tender 11 years old, I experienced my first public undergarment humiliation. My mother and I were riding home in the car after a trip to the department store to purchase my first training bra, and I had taken the bra from its box and discarded the container onto the car’s dashboard. I began the investigation of what would become – at times dreaded, at others welcomed – a familiar garment for my life’s entirety.

Soon after we turned onto Charlotte Lane and headed for our driveway, Mrs. Miller, our neighbor, flagged down the car. My mother slowed to a stop and Mrs. Miller, the mother of six sons, walked over to our vehicle. As they chatted, I saw the daughterless Mrs. Miller spot the bra box in the front window with its “One Size Fits All” label facing up. The next day, everyone on our block, including all the Miller boys, knew that I was on my way to becoming a woman. My family moved away a few months later, so I only had to endure a short period of having my bra strap snapped during our weekly games of touch football in the Miller’s back yard. Thankfully, I never had to face the neighborhood boys as my pubescent young body required more than a mere token of support. Like many women my age, breasts and their plethora of supportive garments have been the source of emotional and physical states – from pleasure and mild embarrassment to nurturance as well as deep betrayal. Breasts are complex body parts that extend far beyond their mammary glands to reach inside our psyches as women. “Boobs and Bras” is an exhibit currently on display at Steaming Bean Coffee on Main Avenue. A juried exhibit of work relating to the theme, the 15 selected pieces are mostly playful and tender descriptions of these secondary sexual characteristic and their attendant societal meaning. This was my intention, as the volunteer juror for the show, to remind us that though there is pain and fear, we can still love our bodies. This sentiment is well stated in Sherry Daniels’ small figurative wall hanging, “Lovingkindness to My Body.” Two other lovingly painted images, a portrait by Kathleen Steventon and one of a pink bra hanging on a clothesline by Marie McCallum, also show tenderness in their renditions. Abstraction makes its way into the show as well with three glass-on-copper enamel wall pieces by Tracey Belt. Referencing women’s social history, Debra Taylor Blair’s encaustic painting “Venus of Will and Hope” plays off of the 25,000-year-old female figurine of the Venus of Willendorf, a symbol of female fertility. Diane Brandt brings us up to date with her mixed-media sculpture, “Swimming Through the Tangle,” an inference, perhaps, to one’s journey through cancer treatment. Marsha Cohen has created, “Who’s Your Sister?” a fiber wall hanging with a collective of colorful, knitted breast-sized shapes. Cohen is using the tradition of “knit-a-tit” as her point of departure, and includes a pocket with the names of women who have lost breasts to cancer and have received knitted breasts to wear as replacements. Carol Ozaki has knitted a bra garment from so-soft bamboo yarn. Nearly half of the works donated by artists were chosen to hang on the Bean’s walls through Oct. 11. All 33 pieces submitted will be auctioned at the Pink Ribbon Affair that benefits women in our region who are undergoing reproductive and breast cancer treatment. The fund is administered by the Women’s Health Coalition of Southwest Colorado and the Women’s Wellness Connection, both programs assisted by the American Cancer Society. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel